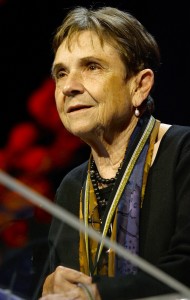

ADRIENNE RICH wrote the poetry and essays that inspired me in my writing. She spoke of desire, community politics, and, above all, of love. Her primary subjects focused on radical ideas about political freedom and social justice. Born in Baltimore in 1929, Rich wrote over thirty volumes of poetry and prose over a sixty-year period and inspired generations of feminist writers. Early on, her work received high praise from the poet W. H. Auden.

In 1953, she married Alfred Haskel Conrad, a Harvard economist with whom she had three children by the time she was thirty. Her 1951 poem “Aunt Jennifer’s Tigers” traces the beginning of her feelings of discontent with her role as wife, mother, and cook. In it, she writes of the massive “weight of uncle’s wedding band.” Rich’s poem foreshadowed the resentment and anger that many women of the 1950’s felt at being trapped in the roles assigned to womanhood within society’s notions of femininity. Then, in 1963, Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique documented the pain of a generation of American women forced to limit themselves to the domestic arena.

Rich came out as a lesbian with the 1976 publication of Twenty-one Love Poems, in which she celebrated her sexuality and love for women. She moved in with writer Michelle Cliff, who became her partner for 36 years, and she continued writing. Her most influential essay, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and the Lesbian Experience,” published in 1980, condemned the erasure of lesbians from mainstream feminism. She was not shy about posing big questions and urging each and every one of us to take them on.

In 1997, she limned the fundamental outlines for what have become the ongoing debates in our society and culture. What is social wealth, and how do conditions of human labor infiltrate our social relationships? What would it take for people to live and work together in conditions of radical equality?

Despite the onset of rheumatoid arthritis, which would take an increasing toll on her life and work, eventually leading to her death, she continued to write and speak about issues of social justice. In 2009, she published The Ballad of the Poverties in the Monthly Review (November, Issue 6):

There’s the poverty of the cockroach kingdom and the rusted

toilet bowl

The poverty of to steal food for the first time

The poverty of to mouth a penis for a paycheck

The poverty of sweet charity ladling

Soup for the poor who must always be there for that

There’s the poverty of theory poverty of the swollen belly

shamed

Poverty of the diploma mill the ballot that goes nowhere

There are types of poverty, among them the world’s oldest profession, that exploit women and force them to prostitute their bodies for money. Here she accuses the powerful of refusing to acknowledge how desperation may lead some women into prostitution to feed themselves and their children.

From the position of a writer who called herself “the poet of oppositional imagination” (Art of the Possible, 2001), Rich reflects back to us a face that many of us resist seeing. In urging us to “know the city you are in,” she asks what the middle-class avant-garde artist can offer the oppressed. It’s a question that continues to linger in the shadows whenever we leave the comfort of our homes and refuse to avert our eyes as we pass by the homeless on our streets. As GLBT people, if we are afraid to speak out, if we let the politics of fear dominate us, then we have only ourselves to blame. This is a message that Adrienne Rich lived her life by as a woman, a Jew, a feminist, a lesbian, and an artist; and she framed the debates that continue to resonate today.

Adrienne Rich entered the larger conversation authentically and let the chips fall where they may. Her conviction that nothing outside of the self is verifiably real rings true for most politically conscious people. In her 1973 poem “Diving into the Wreck” (also the title of her collection), Rich uses the metaphor of a diver exploring a wreck to embody the basic inequality that drives the push for gay and lesbian equality:

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the ones who find our way

back into this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

Cassandra Langer, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a freelance writer based n New York City.