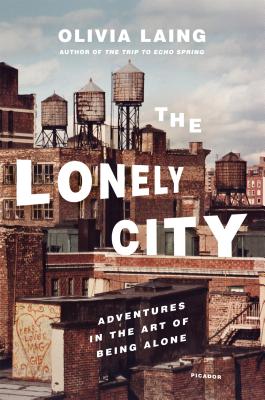

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone

by Olivia Laing

Picador. 315 pages, $26.

“I’VE SPENT much of the last few years in artists’ archives,” Olivia Laing writes on the Acknowledgments page of her new book—partly in Chicago to research the work of Henry Darger, an outsider artist who worked as a janitor most of his life, and partly in Pittsburgh, where she falls in love with the Warhol Museum going through the time capsules Andy left behind: boxes filled with everything from pieces of pizza to New York Posts to personal letters to a mummified human foot. But mostly this is a book about New York, where the author lives in various sublets in Brooklyn, the East Village, and Times Square, as she wanders the city thinking about the artists she feels drawn to in her solitude: Edward Hopper, Andy Warhol, David Wojnarowicz, and Klaus Nomi. It is also a city whose sublets seem to inspire the sort of melancholy that’s inseparable from a nostalgia—evident in books like Patti Smith’s memoir about her life with Robert Mapplethorpe, Just Kids (2010)—for a time when New York was a lot scruffier than it is now. “Most of the time,” she writes, “I sublet a friend’s apartment on East 2nd Street, in a neighborhood full of community gardens. It was an unreconstructed tenement, painted arsenic green, with a claw-footed bathtub in the kitchen, concealed behind a molding curtain.”

“What does it feel like to be lonely?” Laing asks at the outset of her pilgrimage:

It feels like being hungry: like being hungry when everyone around you is readying for a feast. It feels shameful and alarming, and over time these feelings radiate outwards, making the lonely person increasingly isolated, increasingly estranged. It hurts, in the way that feelings do, and it also has physical consequences that take place invisibly, inside the closed compartments of the body. It advances, is what I’m trying to say, cold as ice and clear as glass, enclosing and engulfing.

If all the subjects chosen by Laing have loneliness in common, their sexuality runs the gamut. Half are gay, two are straight, and one is impossible to classify. The book opens with Edward Hopper, the married man whose paintings have become synonymous with American loneliness—though he resisted this interpretation. (“The loneliness thing is overdone,” he said. “I probably am a lonely one.”) The next chapter belongs to Andy Warhol and his desire to hide behind machines like his tape recorder or Polaroid camera, which Laing connects not only with a profound shyness but with an insecurity about speaking (his Slovak upbringing, his Pittsburgh accent). Next is David Wojnarowicz, and his very rough years as a young hustler operating around Times Square at a time when the entire city was, as they say, on the skids. Then the strange life of Henry Darger, a man raised in institutions who spent his life swabbing the floors of another institution, a Catholic hospital, while painting his bizarre imagined universe, The Realms of the Unreal. Then back to New York for Klaus Nomi, the extraordinary countertenor and performance artist who died early in the AIDS epidemic, and Peter Hujar, the photographer who became Wojnarowicz’ mentor before dying, like Wojnarowicz, of AIDS.

When Laing moves to Times Square, perhaps the most alienating of all her sublets, she tells us about Josh Harris, an Internet boy wonder who created the first group house in which people were invited to live in a space where they would be on camera all the time, which leads to meditations on what the Internet has done to our desire for connection. Then, in the last chapter, we return to Warhol, his friend Jean Michel Basquiat, Billie Holliday, and Zoe Leonard, an artist who stitched together the skins of eaten oranges, bananas, avocados, etc., to memorialize David Wojnarowicz, a friend she’d made in Act Up, for an installation called Strange Fruit. Strange Fruit was inspired by the Vanitas tradition in art—a work meant to vanish, like an installation at the Hide/Seek exhibit a few years ago in D.C. (the first show of GLBT artists at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art), which consisted of a heap of candies that visitors were invited to eat, thus making the pile dwindle the way the artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ lover wasted away from AIDS.

If Tolstoy captured the basic human dilemma—that we live and die alone—in his story “The Death of Ivan Illich,” Laing, using the work of psychologists and other writers, takes a more analytical approach. Loneliness, she points out, can be a fear of abandonment, or shyness, or an inability to speak—to voice our feelings and thoughts—or the unsatisfied desire to be watched (leading some people to substitute fame for intimacy), or even hoarding. Henry Darger collected string, and after he died his apartment was found to be stuffed not only with his paintings of little girls with penises but also with the longest novel in American history, albeit unpublished. Warhol collected everything from expensive antiques to cookie jars to—well, go to Pittsburgh and check out the Time Capsules.

If Tolstoy captured the basic human dilemma—that we live and die alone—in his story “The Death of Ivan Illich,” Laing, using the work of psychologists and other writers, takes a more analytical approach. Loneliness, she points out, can be a fear of abandonment, or shyness, or an inability to speak—to voice our feelings and thoughts—or the unsatisfied desire to be watched (leading some people to substitute fame for intimacy), or even hoarding. Henry Darger collected string, and after he died his apartment was found to be stuffed not only with his paintings of little girls with penises but also with the longest novel in American history, albeit unpublished. Warhol collected everything from expensive antiques to cookie jars to—well, go to Pittsburgh and check out the Time Capsules.

Laing’s book is a version of Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, only in this case they are all massively alienated. Warhol, we learn, was not only skittish about being touched by other people, and stayed home from school for a year as a child after a girl in his class kicked him, but gave up trying to acquire friends when he moved to New York and found he could get the company he needed from a television he bought at Macy’s. Wojnarowicz’ father was an abusive alcoholic who killed, cooked, and served his son’s pet rabbit to him at dinner.

These anecdotes come from published biographies, which can seem like potted history, but, as with most biographies, we learn something interesting, like the fact that when Valerie Solanas walked into the Factory and shot Warhol—a horrific scene—he started laughing when Billy Name bent over him sobbing so hard Warhol thought he was laughing. And that the only reason that Solanas didn’t kill Fred Hughes, Warhol’s business manager, was that the doors of the elevator beside her opened at the instant she was taking aim, and Hughes said, “There’s the elevator, Valerie. Just take it,” and she did. This book is about craziness as much as loneliness, or perhaps, to be fair, the point at which loneliness is so intense it becomes the same thing. Solanas was a paranoid schizophrenic who felt Warhol was stealing her ideas—though one never learns why a well-dressed young woman went up to Warhol at a book signing and ripped his wig off. (“Okay, let’s get it over with,” he wrote in his diary. “Wednesday. The day my biggest nightmare came true.”)

Warhol is the most interesting thing in this book, though Laing finds her greatest consolation in the work of David Wojnarowicz (whose short film of ants crawling on a crucifix was withdrawn from the Hide/Seek show after a congressman objected, causing a censorship protest). Warhol was so horrified by death that when his mother, who’d moved in with him in New York, died, he didn’t go to the funeral, and when people asked where she was, he’d tell them she was shopping at Bloomingdale’s. Warhol was an example of fame replacing intimacy, I suppose, though he had boyfriends. Laing’s description of him following Greta Garbo—our icon of loneliness, even if she wanted to be alone—boggles the mind. For queens on the Upper East Side, recognizing Garbo on the street was a sort of parlor game. But then there was the photographer Laing discusses who spent eleven years of his life stalking the actress, so that one can imagine Andy, Garbo, and the photographer all on the same block, locked in a dance of voyeurism and the desire to be alone. The starkest image of loneliness, however, has to be Warhol putting himself into a cab to go to the hospital the night before an operation on his infected gall bladder, an operation Warhol dreaded, and then lying alone in a hospital room after the successful procedure, only to be killed when the negligence of the staff monitoring his fluids led to a fatal heart attack caused by “water intoxication.”

Most people’s loneliness is of the common, garden-variety kind that asks: “Why don’t I have a boyfriend? or “Why am I spending another Saturday night by myself?” One section of the book is about the piers on the Hudson River, where gay men in the ’70s went, not only to find sex but to while away the lonely weekend afternoons when one was a new arrival. The loneliness of Klaus Nomi, Wojnarowicz, Warhol, and Basquiat, however, is on another plane. Yet it’s in working in the archives of these people that Laing finds solace for her own depression. Like so many people, Laing moved to New York for love—but before she got there, the man she planned to live with backed out of the relationship and she found herself wandering its streets with no sense of identity or connection. “When I came to New York,” she writes, “I was in pieces, and though it sounds perverse, the way I recovered a sense of wholeness was not by meeting someone or by falling in love, but rather by handling the things that other people had made, slowly absorbing by way of this contact the fact that loneliness, longing, does not mean one has failed, but simply that one is alive.” Still, there is a wan, listless quality to the voice narrating this story. Sometimes her analyses are spot-on; in other passages, her ramblings make one think of a scene in Robert Altman’s Nashville, when Geraldine Chaplin goes wandering among a parking lot full of yellow school buses with microphone in hand, recording the poetic thoughts to which their emptiness gives rise.

For instance, Hopper’s bleak hotel rooms and cafés lead her to think about Hitchcock’s Rear Window. Elsewhere, she juxtaposes the work of the psychologist D. W. Winnicott with the memorial Zoe Leonard created for Wojnarowicz. Strange Fruit—this mass of fruit and vegetable skins now decomposing at the Philadelphia Museum of Art—provides a theme of stitching things together, which leads to Henry Darger’s hoarding string, which leads to the photographs of his friend Jean Michel Basquiat that Warhol stitched together, which leads to Warhol himself being held together by corsets after he was shot—corsets dyed colors, he notes in his diary, that “are so glamorous, but it looks like no one will ever see them on me—things aren’t progressing with Jon.” This leads to a meditation on the famous portrait by Alice Neel showing a shirtless Andy sitting in his corset, with the scars from the operation he underwent after the shooting plainly visible, which prompts Laing to observe:

So much of the pain of loneliness is to do with concealment, with feeling compelled to hide vulnerability, to tuck ugliness away, to cover up scars as if they are literally repulsive. But why hide? What’s so shameful about wanting, about desire, about having failed to find satisfaction, about experiencing unhappiness? Why this need to constantly inhabit peak states, or to be comfortably sealed within a unit of two turned inward from the world at large?

That captures the mix in this rambling, ambling monologue whose connections can be fascinating or blah, in keeping, perhaps, with the way one wanders a city. In the end it’s best just to go along for the ride and not worry about any single destination or expect anything groundbreaking about loneliness, which is simply too huge a subject to lend itself to any concise conclusions. This “adventure in the art of loneliness” is really about the alienation of certain artists that the author in her own loneliness was drawn to after she was dumped in New York—though her meditation isn’t confined simply to the lonely flâneur. The author expands her focus to include whole groups that society has ostracized—which leads to Billie Holiday’s account of her father’s death from pneumonia because no hospital in Dallas would accept him as a patient, or the image of Holiday herself abandoned on a stretcher in the corridor of the Harlem hospital in which she died before being given a room as a heroin addict.

A paradox that is not mentioned, however, is that the “lonely city” has always been the place where African-American artists, and gay men like Warhol and Wojnarowicz, found relief from their loneliness—immense relief—a rich artistic, social, and erotic life. Warhol had the Factory, Wojnarowicz found a mentor and lover in photographer Peter Hujar. The city was where these two found other people like themselves, not to mention success, self-expression, fame, and fortune (500 million dollars, in Warhol’s case). They weren’t trapped in that forlorn, all-night café that Edward Hopper depicted in Nighthawks. They were at gallery openings and sex clubs. Of course, one can be lonely at galleries and sex clubs, but in a practical sense New York solved the problem of alienation for these men, as it always has for gay people. God knows New York can leave you alone, but I don’t think any of these artists, after a certain point, had that problem. As she wanders from sublet to sublet, Laing seems closer to the garden variety loneliness that most of us feel, especially in a new city, though the list of friends she thanks in the Acknowledgments makes one wonder about even that. Wandering New York all alone is somehow romantic in a way that walking the streets of a small town is not. In Manhattan, loneliness can be æstheticized. Laing’s lament for artists lost to AIDS is also, implicitly, for the city they flourished in, the one that Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg have erased, by cleaning it up. “There is a gentrification that is happening to cities,” Laing writes, “and there is a gentrification that is happening to the emotions, too, with a similarly homogenizing, whitening, deadening effect.”

In her peroration, Laing tells us that there’s nothing wrong with being alone, that we must be kind to one another and dismantle structural ostracism of groups like African-Americans and homosexuals, and stop destroying all the species on this planet besides our own, which is going to make us feel really solitary. All those points are true, but somehow not revelatory. Loneliness morphs as we go through life—the loneliness of a child is different from that of a person in midlife or old age. It even varies throughout a given day and evening. The Lonely City is more particular—about a flâneur’s loneliness (the narrator’s) and the alienation that produces art (her subjects’).