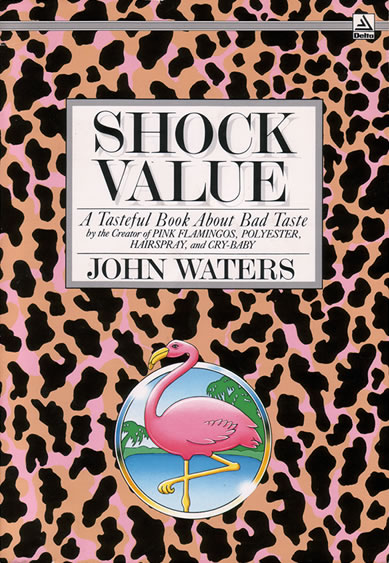

Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste

Shock Value: A Tasteful Book about Bad Taste

by John Waters

Thunder’s Mouth Press

244 pages, $16.95

JOHN WATERS describes Shock Value as “just about my final position paper on the shock/underground period of my career.” Nevertheless, he says, reporters continue to quote from this book when they interview him, as if he hasn’t changed since the 1970’s. So why perpetuate the problem by reissuing it now, 24 years after its initial publication? There are a few new features in this new edition—a foreword by Simon Doonan, an up-to-date (and brief) filmography, and a new introduction by Waters in which he provides brief updates on what has become of many of his collaborators on these early films. Shock Value may be an artifact, but it is a living one, still powerful as the testimony of a filmmaker whose goal is to glory in what most people would prefer to ignore.

Shock Value is largely a memoir, chronicling Waters’ childhood through his first full-length features: Pink Flamingos (1972), Female Trouble (1974), and Desperate Living (1977). But it is also a manifesto that attempts to explain Waters’ æsthetic of shock. The book’s organization follows the conventions of neither the memoir nor the manifesto, being neither strictly chronological nor thematic. Instead, he elaborates on his approach to his work as he moves between chapters about filmmaking and chapters about the rest of his life—including his upbringing, his obsession with criminal trials, his admiration for his great leading ladies Divine and Edith Massey, and the nature of fame.

The æsthetic of shock that Waters lays out piecemeal throughout the book celebrates violence, obscenity, and ugliness. As Waters writes, “I wanted to make the trashiest motion pictures in cinema history.” His glorification of violence may be particularly hard to take, as when he admits that as “the rest of my generation babbled about peace and love, I stood back, puzzled, and fantasized about the beginning of the ‘hate generation.’” But just when you start to get angry about Waters’ celebration of violence, he observes that “I always seemed to meet the best people at riots.” The garden-party casualness of this observation coyly casts the riot as a social occasion and suggests that Waters might have a more complex view of violence than he’s let on. He conceives beauty, too, as a form of violence. “[B]eauty is looks you can never forget,” he writes, referring mostly to looks that are far from conventionally beautiful. “A face should jolt, not soothe.”

That’s what Waters does best, really—he jolts and refuses to soothe. “I pride myself on the fact that my work has no socially redeeming value,” he quips. But that’s not to say that his brand of trash is ephemeral or purely entertaining. Waters seems quite aware of the transformative power of shock. “All my humor,” he writes, “is based on nervous reactions to anxiety-provoking situations.” If you’re paying attention at all, anxiety makes you ask yourself why you’re anxious. At that point, Waters has done his job.

You might expect Waters to write about his childhood and family to explain how he developed his unique sense of taste. After all, he came from what seems to have been a respectable home. But Waters is not especially interested in searching his soul for the traumatic origins of his rebellious, scatological style. For better or worse, there’s not much room for that kind of reflection here; it’s enough to note whichever irregularities of childhood seem to prove that the work to come was inevitable. The story, as he tells it, is that he was born with oddly destructive predilections and then found creative ways to express them. For example, his idea of playing with toy cars was to use them as props in elaborate and violent accident fantasies. Luckily, he had parents who supported him as an artist instead of sending him away. His mother even took him to the junkyard so that he could see actual wrecked cars. And his father provided financial support for his work, in the form of loans, and Waters recalls fondly a scene with his father that evokes images of the burning trailer in Pink Flamingos: “I always felt closest to my father when we stood together and watched a neighbor’s house burn to the ground.” But how many times did this happen?

As if unable to contain his director’s impulse, Waters often turns his focus away from himself, rare in either a memoir or a manifesto. Of course he has much to say about his famous love for his hometown, Baltimore. But his observations about the people he’s worked with—most notably Divine and Edith Massey, both of whom have since died—tell us more about Waters’ vision as it is embodied in the company he keeps. The people he works with, whatever their oddities, are more to John Waters than society’s punchlines. Should anyone doubt the seriousness of Divine’s calling, Waters praises Divine’s work ethic, describing how he lived the life of “a serious actor who wants nothing more than to work every day.” Edith, made famous by her role as the playpen-bound “Egg Lady” in Pink Flamingos as well by her roles in Desperate Living, Polyester, and Female Trouble was miraculously upbeat for someone who survived such a rough life. At the time Waters was writing Shock Value, Edith was running a thrift shop and entertaining the fans who came by just to see her. These are the two female extremes of his early films, one glammed up and the other uglied down, but both shocking in their distance from the usually-accepted norms of female sexuality.

Waters may be right that Shock Value does not represent his current views on filmmaking, but his work continues to bear evidence of a humor grounded in anxiety—especially our fears of ugliness, sex, and disorder. Underneath the Stepford calm of Kathleen Turner’s character in Serial Mom (1994), for example, is a woman driven to violence by violations of perfection and order—an order that, the movie suggests, is itself sick and sterile. A Dirty Shame (2004) revels in the irresistibility of sexual urges, but also in the absurdity of obsessing over them—the movie ends as head butts become the most spiritual of sexual acts. And then there’s Pecker (1998), the most sentimental of them all. Using an old camera from his mother’s thrift shop, Pecker takes beautiful pictures of found objects and the people he meets throughout his day. He tries to explain his artistic vision to his literal-minded girlfriend, Shelley, who is uncomfortable outside the world of the laundromat she runs:

Pecker: Art’s everywhere.

Shelley: Yeah, in my endless bags of dirty laundry.

Pecker: Yeah, it is, if you think about it.

Like Waters, he goes on to show her. It’s too bad, though, that these days fewer people are willing to be shocked, to respond to “anxiety-provoking situations” with reflection instead of dismissal.

Thomas March also reviews for American Book Review. He lives in New York City and teaches at The Brearley School.