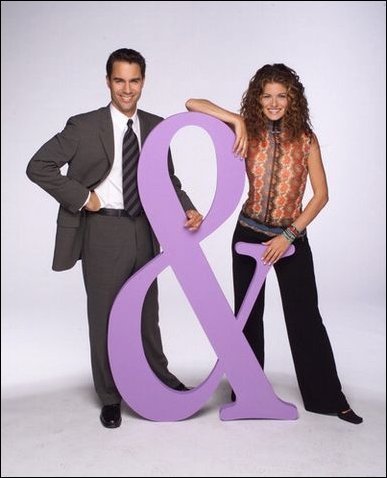

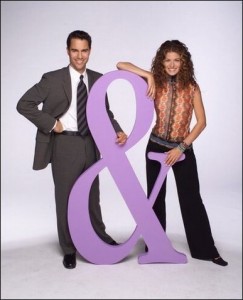

Will & Grace

Will & Grace

NBC. Thursdays at 8:30 PM

Created by David Kohan and Max Mutchnick

LOOKING for civil rights advances in a sitcom may seem an odd venture, but a recent series that screened at New York’s Museum of Television & Radio, “Not That There’s Anything Wrong With That,” would suggest that it’s not an entirely unfounded one. The series focused on a number of TV sitcoms that have gained landmark status for having dealt with homosexual characters, from All in the Family to Ellen. One of the points of a presentation like this one might be to indicate just how far we’ve come. But this series seemed instead to ask, Have we really come so far?

If one sitcom has repeatedly been cited for its groundbreaking treatment of gay characters by a mainstream TV network, it would have to be Will & Grace, NBC’s highly rated take on the lives of a gay man and a straight woman, best friends sharing an apartment in Manhattan. If gay people have often been desperate to see some semblance of the reality of their lives reflected on TV, this show seemed to offer some comfort. But watching Will & Grace over the years, especially this past season, one cannot help but notice a striking disconnect between the show’s internal universe and the external reality of gay people’s lives. This gap was evident in its treatment of the most important issue facing America’s gay and lesbian population right now, same-sex marriage. Even as gay and lesbian couples were lining up to get legally wed in Massachusetts in the wake of the Goodridge decision, Will & Grace seemed to be treating it as still the love that dare not speak its name.

For gay men and lesbians, the stakes are huge. President Bush is pushing for a constitutional amendment to restrict marriage to heterosexuals, while The Advocate and other periodicals, including this one, have discussed the legal and social implications of same-sex marriage in every issue for at least the past year. But Will & Grace has sidestepped the topic altogether. Worse, the show’s plotlines have tacitly endorsed the status quo. In recent seasons, Grace has gotten married to a man (played by Harry Connick, Jr.), while Karen, the show’s secondary female character, has wedded a newfound love (played by John Cleese). So, while Will is still struggling to find a boyfriend, much less a husband, Grace’s marriage is already in jeopardy, suggesting that Grace might be getting a divorce before Will can even tie the knot for the first time. The net effect is to reinforce the old stereotype that gay people are incapable of long-term commitments.

The tepid stance of Will & Grace’s creative team stands in stark contrast to sitcoms of the 1970’s, which often worked to challenge their audience’s perceptions and stereotypes. Witness the outrage over Maude’s famous abortion episode, or the controversy that arose as All in the Family sought to address every conceivable social issue, including homosexuality and homophobia. Most notable of all, perhaps, was the unmarried status of the central character on The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Gently reflecting the burgeoning feminist movement of the decade, Mary Richards was a career woman who liked dating but wasn’t reduced to an emotional mess if a man wasn’t around. Her single status was radical for the time, as all central female characters in sitcoms had up until then been happily married (or otherwise attached to a man, as in I Dream of Jeannie).

Think of the possibilities that Will & Grace offered in terms of challenging viewer stereotypes of gay people. What if Will and Grace had fallen in love at the same time? What if they had chosen to have a dual wedding ceremony, driving home the idea that they considered their marriages to be entirely equal? Or if Will had chosen to marry, while Grace had decided to opt out of marrying her boyfriend, creating something of a surprise twist? These plot possibilities are hardly science fiction; they are going on right now in the lives of thousands of Americans. Some may argue that it’s silly to look to a sitcom for civil rights advances. But many great writers and artists, from George Bernard Shaw to Bertold Brecht to Stanley Kubrick, have recognized the power of humor to make audiences think about social issues in new ways. It was George Orwell who once suggested that within every joke there lies a revolution. So far, I haven’t seen anything revolutionary about Will & Grace. Increasingly, it just feels like a bad joke.

Matthew Hays, a critic for The Montreal Mirror, has written for The Advocate, The New York Times, and other publications.