AS A BIOLOGIST, I have found the arguments against same-sex marriage misguided—not because the evidence hints at homosexuality being based, at least in part, on biological roots, but because the same arguments that are used to keep same-sex marriage illegal could also be applied to some ostensibly opposite-sex marriages. It may be shocking for some people to hear that the sex and gender of every individual in our population does not fit into a conventionally defined box that can be labeled “male” or “female.” Observations that substantiate tremendous diversity in sex and gender within our population pose a biological conundrum: how should we define the terms man and woman, and are they the same as male and female?

Male and female are biological terms used to designate a person’s sex. Generally, the two sexes are distinguished by whether they produce sperm or eggs. In order to do so successfully, each sex needs to possess functioning internal and external reproductive tissues and organs. Yet many of us would have a hard time stripping an individual of his or her sexual designation if the person were for some reason unable to produce viable and/or functioning sperm or eggs. Therefore, we have accepted individuals as being male or female based in large part on how they look physically. For example, a female would possess a vagina in addition to other female-associated parts, and a male would minimally possess a penis.

The development of male and female parts is determined by genetic information organized in the form of genes and contained within our chromosomes. Comprised of DNA, genes can be thought of  as units of information that possess the instructions to make proteins. Proteins are needed to carry out a number of biological processes, and humans have the ability to make thousands of protein types. With the exception of sperm and eggs, the cells of our body possess 46 chromosomes, two of which are referred to as sex chromosomes. The sex chromosomes of a typical male are designated as X and Y, and for a typical female, X and X. Although genes located on non-sex chromosomes also play a role in male and female development, the presence or absence of genetic information on the sex chromosomes, most importantly the Y, is critical in cueing the early embryo to develop male or female parts.

as units of information that possess the instructions to make proteins. Proteins are needed to carry out a number of biological processes, and humans have the ability to make thousands of protein types. With the exception of sperm and eggs, the cells of our body possess 46 chromosomes, two of which are referred to as sex chromosomes. The sex chromosomes of a typical male are designated as X and Y, and for a typical female, X and X. Although genes located on non-sex chromosomes also play a role in male and female development, the presence or absence of genetic information on the sex chromosomes, most importantly the Y, is critical in cueing the early embryo to develop male or female parts.

It might seem reasonable to assume that all males would possess XY chromosomes and associated male physical parts such as a penis, while females would possess XX chromosomes and associated female physical parts such as a vagina; but this assumption would be incorrect. It is estimated that 0.05 percent or about one in every 2,000 individuals in the population do not fit this pattern. For the United States, with a population of some 300 million, this translates into approximately 150,000 people or roughly the population of Dayton, Ohio.

Although there are many examples of how a variation in chromosome composition and concordant anatomy can occur, one example is called androgen insensitivity syndrome or AIS. Individuals with AIS are represented in the population at a frequency of about 1/12,000. In one form of AIS, individuals can look female externally, lacking a penis and possessing breasts. However, they minimally possess the male XY chromosomes and are born with testes that can remain in the abdominal cavity. This condition occurs because the developing embryo possesses a non-functioning form of the gene needed to generate the androgen receptor protein. In their functional form, androgen receptors are capable of binding to an important chemical cue called testosterone, which is needed to complete the development of male-specific reproductive organs and tissues such as a penis. In this condition, the development of XY over XX embryos is affected because the presence of the Y chromosome sets the embryo on a path of male reproductive development that remains incomplete due to a lack of functional androgen receptors.

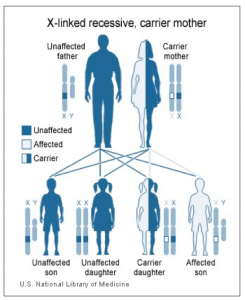

AIS is a genetically inherited trait passed from the mother on to XY children. This pattern of inheritance occurs because the gene for the androgen receptor is located on the X chromosome, and XY embryos receive their X chromosome from the mother. During the process of making egg cells in the ovaries, the chromosome content of pre-egg cells is halved from 46 to 23. The egg cell’s 23 chromosomes constitute 22 non-sex chromosomes and one sex chromosome, the X. If a prospective mother possesses pre-egg cells in which one of her X chromosomes harbors a non-functional gene for the androgen receptor, then fifty percent of the egg cells she makes will carry the faulty gene. In the process of generating an embryo, the egg cell needs to be contacted by a sperm. Similar to egg cells, sperm are produced from pre-sperm cells in a process that takes place in the testes. Each sperm cell will contain 22 non-sex chromosomes in addition to either an X or a Y sex chromosome. Fifty percent of the sperm a male generates will carry a Y chromosome, and if one of these makes contact with an egg cell carrying the nonfunctional gene for the androgen receptor, then an XY embryo, now with 46 chromosomes, will result and develop AIS.

The existence of AIS in the population begets an interesting philosophical question. Are individuals with AIS in fact male or female? If we base the determination on chromosomes alone, then the answer would be male. But because they lack the physical appearance of a male and probably have been socialized as female, many such individuals get married to XY-bearing individuals, otherwise known as men. But can such marriages accurately be characterized as heterosexual? Some would argue that other factors must be taken into account in determining one’s sex. After all, individuals with AIS may never know they are chromosomally male unless they seek medical attention, for example, when they experience pain during sexual intercourse that can occur due to a shallow vagina, or when they fail to menstruate or get pregnant due to the absence of a uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

Should one’s sex then be based on how they look externally? There are cases of AIS in which the individual’s testosterone receptors slightly work, allowing for the development of a penis. Does the answer change in this situation? Does the individual’s possession of a penis and XY chromosomes now make him (or her) a male, even though in every other physical respect this person could pass as female in our society? And if so, would marriage to a typical, non-AIS penis-bearing male be valid in states or countries that outlaw same-sex marriage? Some might argue that depends on the sex the person was assigned at birth. However, what if a sex assignment turned out to not match the person’s gender as socialized?

Although gender is commonly used interchangeably with sex, gender is determined by cultural and social mores and refers to definitions associated with “masculine” or “feminine” patterns of behavior. For most individuals, one’s sex and gender match. For example, males would self-identify as men, and females would self-identify as women. However, in the case of AIS, sexual assignment cannot be strictly defined, or might be inaccurately assigned so as not to match the individual’s gender. What is the marital fate of an AIS individual who has been assigned the sex of female but self-identifies as a male and is sexually attracted to females? Who will this person be allowed to marry legally?

In 48 of the fifty states in the U.S. (Massachusetts and California being the two exceptions), the identification cards presented to the clerk by any two persons wanting to marry must state male on one and female on the other. Matthew Staver, founder of the Liberty Counsel, which opposes same-sex marriage, states flatly that “What you’re born with is what you are.” In essence, marriage legitimacy should be based on birth sex. In 2004 he argued and won a case in Florida that nullified a marriage between a female-to-male transsexual and a female. The court ruled that both individuals shared the same sex, each born female and in possession of XX chromosomes. To be consistent with his own tenet, Staver should be arguing against the legitimacy of thousands of “heterosexual” marriages that are in fact unions between individuals possessing the same chromosome composition.

Biological variation is common among all species and exists naturally. I do not believe we should be trying to establish a list of criteria to determine what defines a man and a woman, and from this a set of rules on who is fit to marry whom. There is no need to call into question the legitimacy of thousands of “heterosexual” marriages that are really, at least from a genetic standpoint, homosexual unions. Instead, we can decide to embrace biological diversity.

Maria Nieto is professor of biological sciences at California State University–East Bay in Hayward, California.