BEAUTIFUL, charming, talented, and celebrated, the toast of Europe and South America during the heyday of her career, Josephine Baker was born in a black slum area of St. Louis in 1906. She was captivating audiences in Paris as an entertainer by the mid-1920’s and achieved acclaim as the 20th century’s first international black female sex symbol by the mid-1930’s. She reveled in her seductiveness onstage and off, living a life that was the very stuff of legend and rumor. Even today, over thirty years after her death in 1975, her name still evokes a sense of glamour and trails an aura of sexuality.

This centennial year of her birth is a fitting time to glance back at the woman and the life that together constitute the legend of La Baker—and it’s especially fitting to examine the legend in a queer context. An African-American by birth who felt more at home in France than in the U.S., a person of virtually no formal education whose ambition and innate abilities allowed her to rise from obscurity and poverty to wealth and fame, a lesbian famous for her exploits with men—these were just some of the contrasts and contradictions in the fantastical life of Josephine Baker. Both her friends and her public recognized the talent, ambition, and sexual provocativeness, but few seemed to see her life as the queer dialogue it was with the world around her. For make no mistake: Josephine Baker led one queer life. It’s not just that she was lesbian or bisexual, although her sexuality was an important part of it; it’s the fact that nearly everything she did expressed desires and needs that deviated significantly from the prescribed social norms of her times. What’s more, to live life on her own terms, she was always willing to transgress those norms at every turn.

Summarizing Baker’s life is no easy matter. It sprawled over seven decades, several continents, many cities, a number of husbands, the adoption of twelve children, numerous performances onstage and in several movies, participation in the French resistance during World War II, and work on behalf of black civil rights after the War, to name a few of her activities. As for her queer life—well, most of the biographies, including her own memoirs (ghost-written by others) and the 1991 HBO film bio The Josephine Baker Story, starring Lynn Whitfield, simply ignore it. The huge exception is Jean-Claude Baker’s 1993 book Josephine: The Hungry Heart.

Jean-Claude knew Josephine well. As explained in his biography, he first met her in Paris in 1957, when he was fourteen years old, and later became a close friend and confidant. After her death, he spent eighteen years working on his meticulously researched biography. Although never formally adopted by her, she considered him one of her own. He loved her deeply enough to change his original last name (Tronville-Rouzaud) by legally adopting hers, and in 1986 he opened Chez Josephine, a bistro located on New York City’s Theater Row that he still runs, which is named after Josephine’s own bistro of 1920’s Paris.

The major sources for this article are Jean-Claude’s biography, comments by him (taped with his permission) at a talk he gave in 1994 at New York City’s LGBT Community Services Center, and two subsequent interviews I conducted with him over the years. I’ll be returning to his views as an authentic touchstone of insight into the woman he still calls his “second mother.”

A Life Lived

To begin at the beginning, then, Josephine Baker was born on June 3, 1906, in St. Louis, Missouri, and, because her mother Carrie McDonald wasn’t married at the time, was given the name Freda J. McDonald at birth. (It’s not known what the “J” stood for. She began to be called “Josephine” some time in her childhood, perhaps because her godmother was Josephine Cooper, the owner of a laundry where Carrie worked.) Already at birth, Josephine had several strikes against her: she was born black in a racist society, she was poor, and she was female. She was put to work at an early age to bring in money, mostly as a domestic in the homes of white families. This meant that by age seven her childhood was over. It also meant that she was placed in a position where she was vulnerable to the sexual advances of predatory white males in the households where she worked, and predations weren’t long in coming.

The full consequences of the sexual abuse Josephine suffered will never be known, but one thing is clear: even as a youngster, it put her in touch with her sexuality in what can only be called an adult way. By age thirteen she was “playing house” with a fifty-year-old steel foundry worker known as “Mr. Dad” who ran an ice cream and candy parlor on the side. The arrangement was a neighborhood scandal, and Josephine’s mother soon ended it. But clearly Josephine had discovered one way of escaping poverty, and she was not averse to pursuing it. Then a few months after the Mr. Dad episode, she married. The fact that she was underage—at thirteen years old so far underage that not even parental consent was sufficient to make it legal in Missouri—seems to have occurred to no one. On December 22, 1919, she became Mrs. Willie Wells, with the blessings of her family, family friends, and the minister who performed the ceremony.

It was not a marriage made in heaven and was soon at an end (though there was no divorce). But if playing the role of housewife was not to Josephine’s liking, she had already discovered one that was: performing onstage, with its attendant right to be the center of attention while you pretend to be something you’re not. She had been fascinated for years by all things theatrical, and in November 1920 her dreams at last converged with reality when Josephine Wells was hired as a chorus girl by Bob Russell of the Russell-Owens Company to tour the black vaudeville circuit with one of his companies. Josephine had secured the job through the influence of Clara Smith, one of Russell’s star blues singers. She became Clara Smith’s protégée—Smith’s “lady lover” in the contemporary lingo of black vaudeville. The implications were as sexual as they sound, according to Jean-Claude Baker’s informants, so people connected with the show knew exactly what was going on.

Once on the road, Josephine’s professional life quickly blossomed. In 1921, she left Russell-Owens to join the resident performing company at the Standard Theatre in Philadelphia. By February 1922, she had joined the road show of the all-black Broadway musical hit Shuffle Along, with music and song lyrics by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle. And on September 1, 1924, she opened on Broadway as one of the leads in the new Blake-Sissle musical, The Chocolate Dandies. Along the way, she made another big change. On September 17, 1921, she married a young man named Billy Baker, the son of a prominent black Philadelphia restauranteur. By the time she left for Europe in September 1925, she had shed the marriage to Billy (without divorcing him) but not the surname. For the next fifty years, she would be known as Josephine Baker.

As a performer, everything was subordinated to Josephine’s ambitions. The people who worked with her found her temperamental, manipulative, devious, and relentless in the pursuit of her goals, but they all agreed that she loved everything about being onstage.

No doubt some of the joy she felt at being part of the entertainment world also lay in discovering the institution of “lady lovers.” The facts are all there, if somewhat hidden in the mad whirl that was becoming Josephine’s life by the early 1920’s. Of course, the effort to hide these facts was an institution unto itself, at least to the extent that one could hide one’s sexual activities in the black performing community of the time. In his biography, Jean-Claude explains the concept of “lady lovers” through the words of Maude Russell, who first met Josephine when both worked at the Standard Theatre in Philadelphia and who later appeared with her in Shuffle Along: “Often … we girls would share a [boardinghouse]room because of the cost. … Well, many of us had been kind of abused by producers, directors, leading men—if they liked girls. … And the girls needed tenderness, so we had girl friendships, the famous lady lovers, but lesbians weren’t well accepted in show business, they were called bull dykers. I guess we were bisexual, is what you would call us today.” These comments make lady lovers sound like little more than some kind of healing program for sexually abused women performers—one way of deflecting attention from the facts of what was going on. But they point to a subset of black performers, both male and female, whose sexual orientation was directed toward their own sex.

So where did Josephine Baker fit into this picture? Her love life involved several marriages and multiple lovers of both sexes, in relationships that varied from one-night and one-afternoon stands to longer-term affairs that went on concurrently both with each other and with her marriages. In the U.S., her lovers and husbands seem to have been exclusively black; in Europe, her lovers were white as well as black, and her husbands were exclusively white. More was known publicly about her male lovers than her female lovers partly because heterosexual behavior was socially acceptable, while queer behavior was not, but also because, as a sex symbol, she had much to gain professionally by the rumors—and sometimes the public acknowledgment—of her liaisons with men. As for female lovers, if Josephine had seen any career advantage to announcing them to the world, no doubt she would have done so. But because she could see no upside to it, she kept quiet about her affairs with women.

Just how many lesbian affairs Josephine engaged in, and with whom, will probably never be known with any certainty. Jean-Claude’s biography mentions six of her women lovers by name: Clara Smith, Evelyn Sheppard, Bessie Allison, and Mildred Smallwood, all of whom she met on the black performing circuit during her early years onstage in the United States; along with fellow American black expatriate Bricktop and the French novelist Colette after she relocated to Paris. Bricktop in particular served as an early mentor who showed her the ropes around Paris for the first few months after her move to Europe.

That move came about when Josephine was hired by a white American named Caroline Dudley Reagan (a confessed bisexual) to star in Reagan’s Paris extravaganza La Revue Nègre. The show premiered on October 25, 1925, at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. It was an immediate hit, and Josephine herself was an instant sensation. Josephine “conquered Paris,” in Jean-Claude’s words, for two reasons: her ability to project an intense sexuality onstage, and the color of her skin. Equating blackness with sexuality is as much a form of racism in France as it is in the U.S., but in 1920’s Paris it worked completely to Josephine’s advantage. She was showered with presents and love letters, and taken out for expensive meals by admirers. She wore the skimpiest of costumes onstage each evening, but was deluged with dresses by Paris fashion designers to wear by day. Crowds followed her in the streets asking for her autograph.

From Paris La Revue Nègre moved next to Brussels, then to Berlin, where Josephine became the darling of café society and was soon partying with the likes of German publisher and art collector Count Harry Kessler, playwright Karl Vollmoeller, and theater director Max Reinhardt. In Berlin we can discern another strand in her queer life. Although Jean-Claude describes the following incident in his biography, I quote here from the published diaries of Count Harry Kessler, who was himself homosexual:

Saturday, 13 February 1926 Berlin. At one o’clock … a telephone call from Max Reinhardt. He was at Vollmoeller’s and they wanted me to come over because Josephine Baker was there and the fun was starting. So I drove to Vollmoeller’s harem on the Pariser Platz. Reinhardt and [the other male guests]were surrounded by half a dozen naked girls. Miss Baker was also naked except for a pink muslin apron, and the little Landshoff girl [Vollmoeller’s mistress] was dressed up as a boy in a dinner-jacket. Miss Baker was dancing solo with brilliant artistic mimicry and purity of style. … The naked girls lay or skipped among the four or five men in dinner-jackets. The Landshoff girl, really looking like a dazzlingly handsome boy, jazzed with Miss Baker to gramophone tunes.

Vollmoeller had in a mind a ballet for her [Josephine], a story about a cocotte [kept woman], and was proposing to finish it this very night and put it in Reinhardt’s hands. By this time Miss Baker and the Landshoff girl were lying in each other’s arms, like a rosy pair of lovers.

At some point in the Berlin run of La Revue Nègre, and just three months after arriving in Europe, Josephine broke her contract with Caroline Reagan and returned to Paris to headline in a new show at the Folies-Bergère. It was there that she donned her most famous costume: a belt of bananas (and little else). It wasn’t long before she was taking lessons in French and thinking about becoming a French citizen.

In 1926, a gigolo named Giuseppe Abatino, nicknamed Pepito, entered her life as both mentor and lover. With Pepito’s help, and her own flair for the grandiose, Josephine began to transform herself from a popular entertainer into an international legend whose stature eclipsed that of Mistinguette, reigning queen of French musicals, and eventually rivaled that of Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, her contemporaries on the stage and screen. Her own movies included the silent film Siren of the Tropics in 1927 and the talkies Zou Zou in 1934 and Princess Tam Tam in 1935. Even the Great Depression had little effect on her fortunes: the 1930’s were mostly spent performing in Paris and on international tours, buying homes, making movies, running her Paris nightclub Chez Josephine, and making—and spending—a great deal of money.

In 1935 she ended her relationship with Pepito. On her own once more, she set out in earnest to find herself a French husband, which she succeeded in doing so that on November 30, 1937, she wed the (white) French businessman Jean Lion (without, it should be noted again, having divorced either Willie Wells or Billy Baker). This marriage, like its predecessors, didn’t last long, but it accomplished one all-important goal: as the wife of a Frenchman, she could now claim French citizenship under French law, and within four days of the wedding she had obtained her French passport.

Josephine and Lion were formally divorced in April 1941. In the meantime, World War II intervened. Such circumstances test the mettle of every citizen, and by all accounts Josephine acquitted herself well as part of the French Resistance, first in France during the “phony war” before the Germans actually invaded her new homeland, and later in North Africa. When she returned to Paris in October 1944, after its liberation, she was greeted by throngs of people on the Champs-Élysées welcoming her home. She was also awarded the Medal of Resistance and eventually the Légion d’Honneur by France in recognition of her wartime work. She also met and became involved with Jo Bouillon, a (white) French jazz bandleader, whom she married on June 3, 1947, her forty-first birthday. This marriage was no more legal than those that preceded it, and no less troubled, but it lasted a great deal longer—to the end of Josephine’s life nearly thirty years later.

The durability of this marriage was due in part to a crusade against racial discrimination that Josephine had undertaken after “rediscovering her race” (in Jean-Claude’s words) during World War II. Over the years she gave talks on the subject, challenged segregation laws when in the American South, and marched for civil rights with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at the historic March on Washington in 1963. She was so vociferous in her denunciations of American racism at various international forums that the FBI compiled a dossier on her activities and the CIA kept tabs on her. But arguably her most public activity was an experiment in racial harmony that she undertook at Les Milandes, a château in southern France that she bought after the War. There she assembled what she called her “Rainbow Tribe” of twelve children that she and Jo Bouillon adopted from different parts of the world. (Because of a congenital malformation of the uterus, Josephine was unable to have children herself.) All the children were given Bouillon’s last name, and they were the glue that kept the marriage contract itself in force long after the couple’s spousal relationship had come to an end.

By all accounts race relations were harmonious enough at Les Milandes. However, personal relations were anything but peaceful, especially between Josephine and Jo Bouillon. Much of the problem could be traced to Josephine’s impulsiveness, extravagance, and need to control all aspects of life at the château. Her experiment would have been an expensive undertaking under any circumstances, but her own temperament and inability to handle money gave rise to much friction. The situation wasn’t helped by Josephine and Jo’s differing sexual needs. Bouillon never hid his homosexuality from Josephine. At times he even seemed to flaunt it as a way of asserting his independence from a wife whose imperious personality and demands continually overwhelmed him. Josephine, for her part, flaunted her affairs with women. In his biography, Jean-Claude quotes a French informant as saying: “Josephine and Jo … used to fight in the streets of Castelnaud [a village near Les Milandes]. She would scream ‘Faggot!’ [and]he would yell ‘Dyke!’ They weren’t hiding anything. Jo would come to our house with another man, their arms linked, Josephine would find happiness with a girl from a Paris ballet company.” In Josephine’s last years, according to another informant, she “surrounded herself with women, nurses, secretaries. A lot of young girls were in her entourage, so people talked, but by then they had seen so much that nothing could surprise them.”

In 1960, Jo Bouillon decamped (without divorcing Josephine) to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he established a new life as a restauranteur. In 1968, creditors foreclosed on Les Milandes. Josephine was still performing onstage, but the money no longer flowed as freely as before. She was perpetually in debt, and she and her children were increasingly dependent on the generosity of benefactors like Prince Rainier and Princess Grace of Monaco.

In bad health for years, Josephine finally collapsed from a cerebral hemorrhage in Paris on April 10, 1975, the day following a triumphant stage comeback, and died two days later without regaining consciousness. Three funerals were held in her honor, one in Paris and two in Monte Carlo. At the behest of Princess Grace, she was buried in Monaco—a great distance both in miles and in circumstances from her humble origins in St. Louis nearly 69 years before.

A Life Examined

Parsing Josephine Baker’s queer life is problematic. It’s true that by age fifteen she was already participating in what would prove to be a lifelong string of affairs with other women. Yet she was always careful to hide these liaisons from her public. Moreover, according to Jean-Claude, although she had many gay friends, on occasion she exhibited a real streak of homophobia. Case in point: the one lesbian experience she was willing to put on record was an incident she described in her 1935 memoir, Une Vie de Toute les Couleurs, as having occurred in 1925 while she was appearing at the Plantation supper club in midtown Manhattan. According to Jean-Claude’s biography, she and three other “cabaret girls” were invited to dine at the home of a famous (but unnamed) New York actress. When she discovered that the actress expected a sexual five-way as the dessert course, Josephine says she “was furious and created such a ruckus that I was thrown out.” Did the incident actually occur? Probably—but perhaps not in quite the way Josephine described it. She was always good at covering her tracks when she wanted to, or even creating false tracks if she thought the situation warranted it. Against the libertine reputation she had acquired in Europe by the 1930’s, she’s seen here as trying to project an image of herself as sexually naïve.

As a second example, several years after Jo Bouillon moved to Argentina, she exiled one of her Rainbow Tribe sons to Buenos Aires to live with his “faggot father” after discovering he was having sex with another young man. Her excuse: she didn’t want him “contaminating” his brothers.

Of course, Josephine lived in a highly homophobic era that left most GLBT people, especially those in the public eye, little wiggle room when it came to protecting themselves from antigay bigotry and harassment. But that doesn’t excuse her own homophobia. It was an ugly part of her character, and it could certainly be damaging to those, like her son, who felt its effects personally. She was, at any rate, no queer role model. Still, something in her performances and even in her personal life spoke to her gay admirers, especially gay men, who were always drawn to her. Indeed, by the late 1960’s, according to Jean-Claude, gay people made up “eighty percent of her faithful audience.”

You don’t have to go far to see why. Her life pulsated with needs and desires that can only be called “queer,” animated by a queer energy that reached her audiences regardless of how carefully she tried to keep the gay aspects of her life hidden. One reason for this: by late in Josephine’s career, her performances had something of the camp about them. “Onstage she looked like a drag queen,” said Jean-Claude in an interview. “A badly made-up drag queen—glitter over her makeup, too much mascara, extravagant gowns that exaggerated the feminine, extravagant gestures. Nobody else performing in Europe during the 1930’s moved like she did. Later, here in the U.S., it would be called ‘vogueing.’” Another reason she connected with gay audiences is that she challenged the rules of acceptable sexual behavior in public, something that would have been a big draw for those whose sexuality was stigmatized as socially unacceptable or even criminal.

On top of that, much like Judy Garland and Billie Holiday, Josephine communicated with audiences from a vulnerable part of herself, a part that had been hurt and was still suffering, connecting with them as a survivor of abuse and helping them to realize that they could survive their own traumas. In Jean-Claude’s words: “She was burning in hell from all the pain and abuse, but she was able to shut up her feelings within herself and give it back to people in a majestic and generous way. She was one of those exceptional people who know how to break down barriers to reach and touch the body, the soul of anyone.”

Jean-Claude subtitled his biography “The Hungry Heart.” But Josephine’s was also a hungry queer heart, aching all her life for the love and acceptance she felt denied her as a poor, abused, black child in St. Louis. She couldn’t heal herself, but when she sang as a survivor, it was a message welcome to gay people’s ears. No wonder the legend of La Baker is still alive and well. For gay audiences, it will probably live on for many years to come.

Note: All three movies starring Josephine Baker were released as DVDs in 2005 by Kino Video.

Sources

Baker, Jean-Claude, and Chris Chase. Josephine: The Hungry Heart. Random House, 1993.

Baker, Jean-Claude. Author interviews, February 28, 1995, and May 17, 2006.

Baker, Jean-Claude. Talk at New York City’s LGBT Community Services Center, September 13, 1994.

Dudley (Reagan), Caroline. Detail: La Révue Nègre (unpublished manuscript, used with permission of Caroline’s daughter Sophie Reagan Herr).

Kessler, Harry. Berlin in Lights: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler (1918 –1937). Grove Press, 2000.

Rivollet, André. Joséphine Baker: Une Vie de Toutes les Couleurs. B. Arthaud (Grenoble, France), 1935.

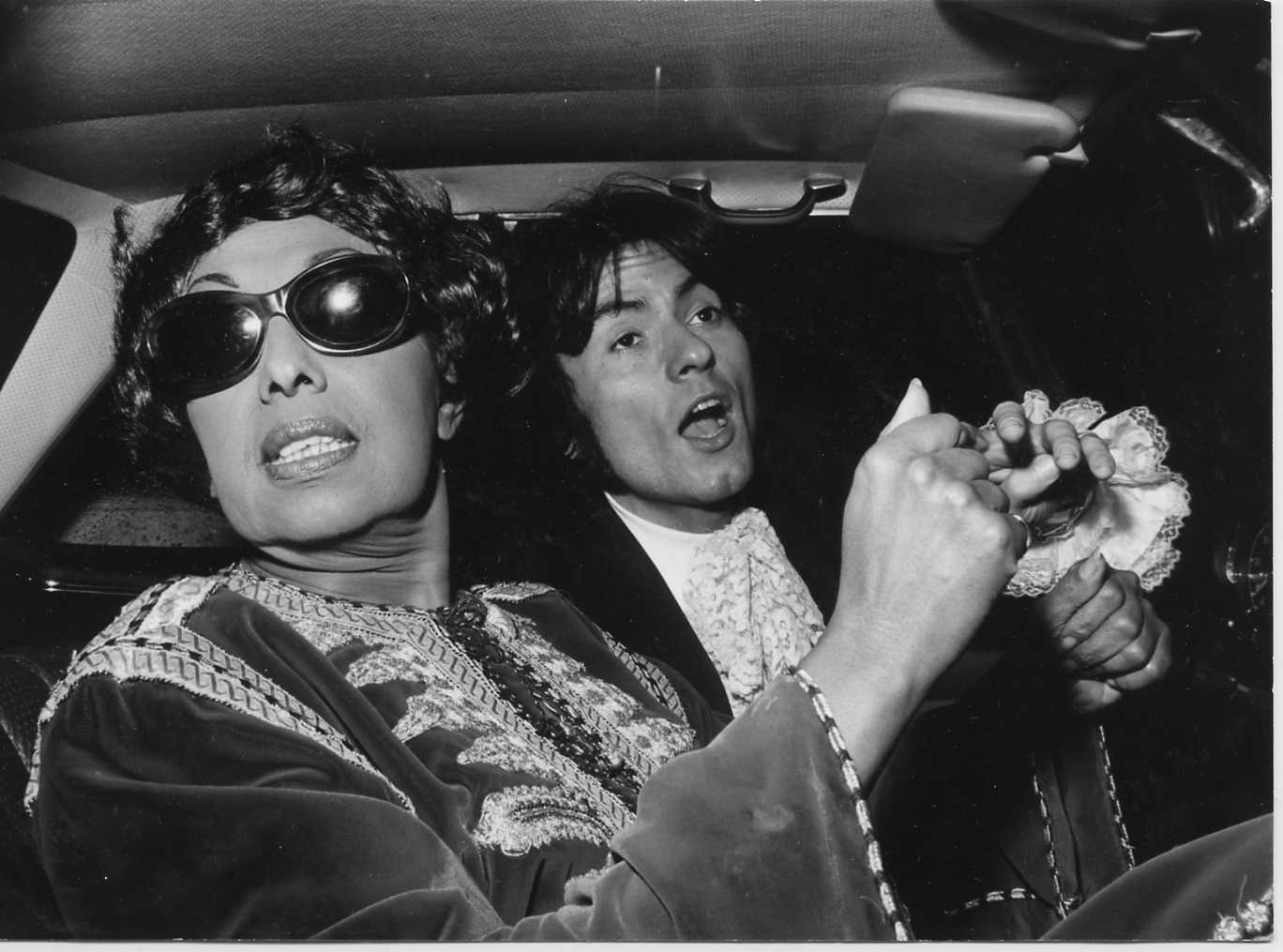

All art for this piece courtesy of the Jean-Claude Baker Foundation.

Lester Strong is special projects editor for A&U magazine and a regular contributor to OUT magazine.