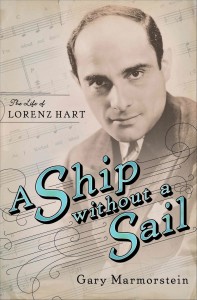

A Ship Without a Sail: The Life of Lorenz Hart

A Ship Without a Sail: The Life of Lorenz Hart

by Gary Marmorstein

Simon & Schuster. 531 pages, $30.

EVER WONDER how American popular music went from “Some Enchanted Evening” to “Me So Horny”—from “If I Loved You” to gangsta rap? And why we seem stuck at the latter—why nothing has succeeded it? Musical groups proliferate with such rapidity now that one barely has enough time to admire the cleverness of their names; but that’s all that seems clever anymore—their names—because when you hear the music in this ever-recombinant culture of ours, you’re always struck with the same reaction: This is just [fill in the blank] crossed with [fill in the blank].

For whatever the reason, it’s useful to learn, in a new biography of Lorenz Hart, that a century ago the Broadway musical—which, before rock ’n roll, epitomized American popular music—was equally stuck in the clichés of the European operetta. At least, that’s how a group of young, mostly German- and Russian-Jewish songwriters in New York felt. The fun part of A Ship Without a Sail, Gary Marmostein’s new biography of Hart, is actually the early 1900s, when Lorenz Hart and Richard Rodgers (originally Rogozinsky), Oscar Hammerstein, Yip Harburg, Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, and Harold Arlen were all trying to write songs that sounded less like Sigmund Romberg and more like the city in which they were living. (Rodgers and Hart’s first hit was “Manhattan.”)

Hart grew up on the Upper West Side, the son of a father whose business ethics and ties to Tammany Hall got him sent to jail at least once—a man so vulgar that a friend visiting his son remembered watching the father piss out the third story window of his son’s bedroom “with no trace of self consciousness.” Lorenz, or Larry, as he was always called, was quite the opposite: sensitive, funny, extremely well read, and, after dropping out of Columbia, always writing lyrics for revues. Richard Rodgers, the son of a doctor who lived on West 86th Street, was only 16, and Hart 23, when they became partners in an attempt to infuse the operetta-derived musical with the brashness and energy of contemporary life—or, as Hart put it, to write lyrics that sounded the way people actually spoke.

Another reason the first part of this biography is fun is not simply because all these young men were ambitious and talented and living in homes that bring to mind You Can’t Take It with You (the comedy by George Kaufman and Moss Hart, also contemporaries), but also because they came of age when so much of New York was literally new. Bridges, tunnels, subways, the light bulb that made the theater district the Great White Way—a cultural golden age was just beginning. People who argue that Hart wrote uniquely sophisticated lyrics will have to contend with the fact that there seems to have been something in the water at that time that produced the same urbane wit in the work of the Gershwin brothers, Jerome Kern, Harold Arlen, and Irving Berlin. (The only Gentile in the bunch was Cole Porter, who, when Rodgers and Hart visited him in Europe before Porter had made it big, told his visitors that he had discovered the secret of writing hits: “I’ll write Jewish tunes.”) The truth is, lots of people seemed to be writing the sort of sadder-but-wiser song we treasure in cabaret today. Rodgers and Hart created “Little Girl Blue,” but the Gershwins gave us “But Not For Me,” Arlen “The Man Who Got Away,” and Cole Porter “I Concentrate on You.” They’re all the same song, in a way.

But it’s Rodgers and Hart’s “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” that may be the best example of the erotic Welt-schmerz that Hart brought to Rodgers’ music. The erotic punch of “I’ll sing to him, each spring to him, and worship the trousers that cling to him” is so strong that later singers, including Doris Day and Ella Fitzgerald, felt obliged to change it to “and long for the day when I’ll cling to him.” Even now, the specificity, the power, of those trousers jolts the listener—the gay listener in particular. It was obvious to everyone that Hart was attracted to other men—and, to add to the difficulty, felt himself to be so short and homely that no one could possibly be interested in him. (Cue “My Funny Valentine.”) But the problem for the biographer is that there is so little to go on—no record of a hook-up, much less a lover; no gay bar, though Hart did go to the Turkish baths used by both straight and gay men at a time when even gay gatherings in cafeterias were monitored by the police. What happened was that Hart would simply, when he wanted to, disappear—and no one could find him till he came home drunk the next morning, or was found on a curb somewhere, beaten up so badly he had to be hospitalized. His sexual or romantic life remained a secret.

One wonders if that’s why Marmorstein spends so much time summarizing the plots of the flimsy books around which Rodgers and Hart wrote their music: there is no data on Hart’s private life. (The only other case of a gay life as devoid of evidence as this is one is, oddly, John Singer Sargent.) Of course, that can’t really be why Marmorstein, in a story as rich with research as this, bothers to summarize these shows’ books. Mavens of the Broadway musical are like sports fans who passionately trade obscure statistics about baseball players. How else to explain the summaries of mindless trivia about the plots Rodgers and Hart worked with? Rodgers and Hart got their start writing songs for revues, graduated to musicals based on literary classics (A Connecticut Yankee; The Boys From Syracuse) and finally took their material from contemporary life—to wit, Pal Joey, a musical about a lounge lizard whose “depravity” and “scabrous lyrics” so upset Brooks Atkinson in The New York Times that he said it raised the question: “Although Pal Joey is expertly done, can you draw sweet water from a foul well?” This sort of prudery frustrated Hart. Pal Joey was part of his quest to bring the musical down from its Sigmund Romberg fantasies to street level. Perhaps it’s all about the street in the end; that’s where the energy lies.

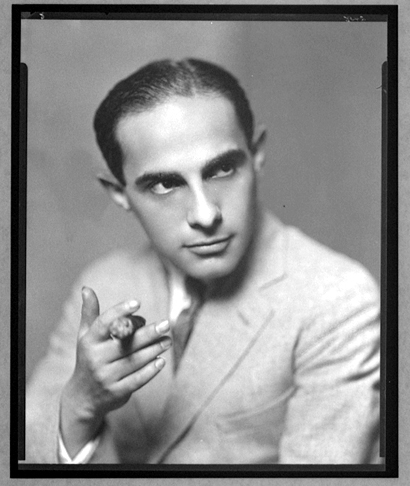

This is a book with which to escape the present—a saga of two glamorous careers, two men who, even before they’d written their biggest hits, were already working for Hollywood (though Hollywood would buy a show by Rodgers and Hart and then throw out all or almost all of their songs and replace them with the work of other composers, a logic that is hard to follow). The photographs that illustrate the book, like the life, seem glamorous on the page, but in reality before very long Hart’s alcoholism started to cause difficulties for the partnership. Famous for being able to come up with new lyrics on the spot—he’d scrawl them on the back of an envelope—the problem was finding Hart in the first place. Rodgers had to resort to all sorts of stratagems to get him to work. As the years went by and their success increased, the other line on the graph—Hart’s sobriety and availability—was going in the other direction, until finally the inevitable moment came when Rodgers went looking for another partner, and found one, in Hart’s own friend from college, Oscar Hammerstein II. (That they were all friends is part of the charm of this book, and its ultimate sadness.) The Hollywood movie (Words and Music) based on the lives of Rodgers and Hart, like the one based on Cole Porter, was completely fabricated, leaving out, in both Hart’s and Porter’s case, the same-sex attraction, and, in Hart’s case, the addiction to booze. Had Hollywood made a movie about that, it would have put The Lost Weekend in the shade.

Whether alcoholism was a genetic predisposition or Hart could not handle his homosexuality or what he saw as his lack of physical charm, it’s impossible to say. Larry Hart, the generous, funny, endearing gay friend to so many, remains in the end a total enigma. Suffice it to say, the story of Rodgers and Hart makes the role reversal in A Star Is Born look sunny. That Rodgers’ first post-Hart musical should be Oklahoma!—a success Hart was still alive to witness—makes the contrast between the two men’s fates all the more dramatic. After Oklahoma!, Rodgers went on to create Carousel, The King and I, South Pacific, and The Sound of Music, among many others. (Noel Coward said of Rodgers: “he positively peed melody.”) Worse, a few weeks after the opening of Oklahoma!, Hart’s mother died. Marmorstein reports that Hart was hardly ever sober after the death of the woman he’d lived with all his life—even during the revival of A Connecticut Yankee that Rodgers instigated that summer in order to give his ex-partner something to do. It didn’t work; Hart kept drinking, while Rodgers went on with a new partnership that would prove so successful that when Moss Hart was visiting friends during the try-outs for The King and I, and his hostess looked out the window and asked what could possibly be under the tarp on the big barge making its way down the East River, Moss Hart replied: “That’s Rodgers and Hammerstein sending their money down from Boston.” As for Larry Hart, he died in November, eight months after the opening of Oklahoma! and seven months after the death of his mother.

Years later, after Rodgers had lost Hammerstein as well and he was writing his first musical by himself (No Strings), he told his lead, Diahann Carroll, when she asked about Hart: “You can’t imagine how wonderful it feels to have written this score and not have to search all over the globe for that little fag.” One’s first reaction is to be taken aback, to chalk it up to the famous womanizer’s homophobia; but reading this book, you see it in a different light. When Hart died at 48 of pneumonia in a New York hospital (after a friend found him sitting in the gutter outside a bar on 8th Avenue), Rodgers “took one last look at his partner of twenty five years” in the coffin … turned away, and collapsed, sobbing, into his wife’s arms.”

One begins this book perhaps knowing already that Hart had a difficult personal life—he seems to stand for every queen getting quietly soused in a midtown bar even now—but one ends not really knowing the source of his self-destructiveness, or his gifts. Hart wrote an unpublished essay complaining that Tin Pan Alley had become all technique, like the lighting men in the theater who wanted a laugh at the end of a song before a black-out. But lyric writing was not a science, he said, it came from the heart. Hart’s heart is what remains a mystery here. In a book so stuffed with information, we get little interpretation—of even the relationship between Hart’s private life (a mystery) and the words he wrote. But it was a gay man, Alec Wilder (“I’ll Be Around”), who coined the term the “American Songbook,” for this music that has become a hallmark of urban, and gay, sophistication; and it’s no coincidence that two other gay men, the late Bobby Short and Michael Feinstein, have devoted themselves to this music.

People ask if there is such a thing as a gay sensibility. If there is, one is tempted to offer Hart’s work as a prime example. For whatever reason, he brought a heartfelt romantic longing to lyrics that is as distinctive as Schubert’s tenderness. Critics say that Hammerstein’s optimism made Rodgers’ music less complex, and watching the recent Carousel with Nathan Gunn, it’s hard to imagine Hart writing a song about June bursting out all over, much less “You’ll Never Walk Alone.” But is this because Hammerstein was a married father and Hart an alcoholic homosexual? That sounds a bit simplistic. The very heterosexual Richard Rodgers ended up with a drinking problem too. It’s tempting to think only an unhappy queen could produce lines like “All alone, all at sea/ Why does nobody care for me?” But Hart wrote upbeat lyrics as well (“The Lady is a Tramp”), and very sweet ones (“Have You Met Miss Jones?”), and some that sound almost mystical (“Where or When”). But his public persona seems linked to songs associated with a sort of love hangover (“I Didn’t Know What Time It Was,” “It Never Entered My Mind,” “He Was Too Good To Me,” or the aptly named “Glad To Be Unhappy”). Clifton Fadiman wrote: “The Rodgers-Hammerstein purified musical comedy, with its stress on the wholesome, has weaned us away from the indiscretions, with their mild suggestion of the street corner, of the Larry Hart school. One feels some embarrassment, too, the embarrassment that comes of listening to the small boy saying something shocking in the drawing room.” What was shocking in the drawing room, what gave Hart’s lyrics some of their heart, seems, to this reader at least, to have been the world into which Hart disappeared when no one could find him.

At the end of his book Marmorstein finally gives us the overview we’ve been wanting when he articulates what set Hart’s work apart from that of other lyricists. (Listening on YouTube to the myriad versions of Hart’s songs will also do the job.) Marmorstein concedes what Rodgers called Hart’s “pinwheel brilliance” to only one other lyricist, Cole Porter—though he quotes Hugh Martin on the difference between the two: “Cole Porter was all about sex, Larry was about love.” Isn’t what makes Hart so powerful that he blended, as many gay men do, the two?

Readers can make up their own minds, though they’ll be tipped off about Marmorstein’s take on his subject not only from his title (taken from one of Hart’s songs), but also by the epigraphs he has chosen for his book. One comes from that classic of frustrated romance, Cyrano de Bergerac, the other from novelist Dawn Powell’s diary on March 1, 1939: “Wits are never happy people. The anguish that has scraped their nerves and left them raw to every flicker of life is the base of wit—for the raw nerve reacts at once without any agent, the action is direct, with no integumentary obstacles. Wit is the cry of pain, the true word that pierces the heart.”

That’s why, presumably, men still sit in dim rooms in Manhattan, listening to the latest interpreter of these songs, and why the Great American Songbook has become, as Marmorstein says, America’s classical music. A Ship Without a Sail reminds us that this music came from below—in this case, from people who were gay or Jewish. Since then, other outsiders have moved pop music along, though what pop music is nowadays is hard to say. Part of the thrill of gay clubs in New York in the ’70s was precisely the knowledge that we were dancing to music no one could find on the radio (unless it was WBLS)—music that required decades before it ended up in aerobics classes at the Y. But the Broadway musical has long since ceased to be a source of hits. Given the new technology, we are so Balkanized now there may not be such a thing as American popular music—though one shouldn’t romanticize the past. In 1940, when Hart was asked about a turf war over music licensing that had led to the radio stations’ boycott of Broadway songs, Hart replied: “Nobody cares anymore whether a song is good or not. People just listen to bands.” Now they’ve got iPods. I hope some Rodgers and Hart is on yours.

Andrew Holleran’s latest book is Chronicles of a Plague, Revisited: AIDS and Its Aftermath.