Cock

Directed by James Macdonald

At The Duke on 42nd Street, NYC

MIKE BARTLETT’S new play Cock, which last year won an Olivier at London’s Royal Court, has come to the Duke on 42nd Street in its London production, with the Court’s director, James Macdonald, once again shaping this relentless verbal battle that leaves no survivors. It is sometimes called a comedy; I found it immensely sad. The title might seem obvious, since the phallus looms large in the play. The size and sight of the genitals of the male participants are more than once brought up for consideration, although in a refreshing change from most contemporary theater, everyone keeps his or her clothes on, and the audience is asked to use its imagination.

The story is ostensibly about a seven-year gay relationship threatened by the younger man’s defection to the bed of a woman he has met going to work. You could say that the fight over him is really about who’s going to get to enjoy his cock. The New York press, ever demure, generally refers to the play in print as “Cockpit,” an allusion to the wooden construction of the theater as seats in concentric rows from which the audience looks down at the two main characters lunging at each other verbally and physically, which, along with the broken bits of dialogue—more weapons than words sometimes—immediately recalls the fight to the death of two male birds, typical of the many provocative and rewarding ambiguities of this drama.

Throughout the play there are no props, nothing to impede the flow of brutal assaults in the fight put up by M (Man) for John, and then against W (Woman). All the while John is attempting to stake out his own position. While John’s halting response to the abrupt, aggressive remarks addressed to him marks him as their victim, he sometimes appears to be an annoying kid who can’t make up his mind.

The two men having a go at each other in the pit are about a decade apart in age, maybe late thirties and late twenties, but the younger looks and acts like a teenager, which might cause viewers of a certain age to recall the terms “chicken” and “chicken hawk” to describe the two parties. The older male picks at his often inarticulate young partner with a relentless barrage of cruel irony that brings to mind a Bette Davis impersonator. The one-liners can be funny, but the style seems dated—The Boys in the Band back from the grave—so the humor is lost, especially as a response to the boy’s utter seriousness when trying to make his point. Jason Butler Harner as M, determining to keep the boy, speaks like a vicious “cock of the walk,” though his body language registers immense despair at certain moments, however brief, when he relaxes his aggression.

In London, the play was sold out for the run before it opened, and I suspect that casting the glamorous stage and screen sensation Ben Wishaw (Bright Star) as the boy-toy helped the box office. I cannot imagine anyone, however, conveying the heartrending vulnerability of John better than this production’s Cory Michael Smith. He is excellent at playing off the vulnerability and desirability of his impossibly slim body, about which the Woman says: “Some people might think you were scrawny. Like drawn in with a pencil. You need to be filled in.” Smith’s beautiful eyes, of which the character John is very proud, are magical in how he employs them to suggest the yearning, the hurt, and the confusion that haunt this lost or befuddled soul. It would be easy to say that John is bisexual or momentarily mistaken about his orientation, but what Smith brings to this role is the character’s change in intensity, emotion, and affection as he confronts the other people in this triangle. He is confused, they say, but those eyes say that at each moment he is altogether there in that moment; it makes him a person who is both tentative and incoherent.

The drama moves to what seems to be the conventional collision when M has John invite the Woman to dinner, except, of course, like every other perversity in this play, M is revealed to be even more pathetic when he announces that he has asked his father along for moral support. And it is shocking, really, that just as he’s losing the game, M is propped up by the entrance of his father (played by Cotter Smith), a welcome relief of stereotypical bluff and authoritative manliness—thundering stereotypical heterosexuality—dropped into the endless jockeying for position of the other three. This is indeed a dinner party from hell.

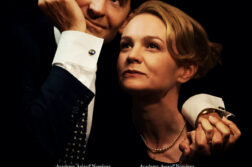

Woman (played by Amanda Quaid) is as good looking as the younger man and as aggressive as the older one. Unlike the fighting males, who are dressed in nondescript clothing that does nothing to enhance their sex appeal, Woman wears a low-cut dress that suggests the eternal feminine archetype of the maternal, nurturing helpmate. She is thus marked as something of an Other, theoretically speaking, as distinct from the males, whose clothing leave them unmarked: they have no discernible chests, thighs, or crotches under their clothes.

Identities or categories are what it’s all about in this play. “I’ve never found women attractive,” says John. “I’m not women, I’m me,” she replies. John can make the distinction between a desire for the heterosexual life and his desire for W, when he says in his typically mangled way: “I’m so happy, I was so worried that although that’s what I thought I really was into sexually, romantically everything I was worried that actually it was just wishful thinking that maybe I wanted the children and the house and the life and what I considered normality, and that was really what I—but it’s not. It’s something really simple. It’s this. There it is looking at it. It’s simple. I just fucking fancy you so much.”

But Father will have none of it. In a play dominated by rapier thrusts of brief dialogue, he delivers an oration outside of the pitched battle raging at the dining table in which he talks of the history of his change of heart about the gayness of his son, and ends by insisting that gay is normal now and John must accept it. In an extraordinary rejoinder, Woman attempts to demolish the Father’s speech by describing in detail how his gaze played (hetero)sexual politics with her body all the while as he defended John and his son’s relationship, which leads to the triumph of the male, so to speak. When the play ends, the young man is crouched on the floor in surrender to his partner’s barrage, while the older men insistently hand the Woman her coat and usher her out the door. And yet, one doubts that John will ever have sex again with M, or whether indeed he will manage to get that cock up for anybody after what he has been through.

Charles Rowan Beye formerly taught ancient Greek language and literature. His memoir My Husband and My Wives: A Gay Man’s Odyssey will be published in October (Farrar, Straus and Giroux).