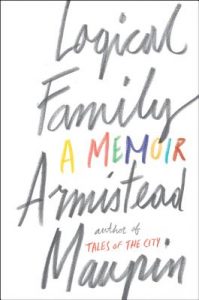

Logical Family: A Memoir

Logical Family: A Memoir

by Armistead Maupin

Harper. 304 pages, $27.99

IN his semi-autobiographical novel The Night Listener (2000), Armistead Maupin’s fictional alter ego Gabriel Noone makes the following observations about storytelling: “I’m always too aware of the effect I’m making. I’m afraid people will lose interest if I don’t keep tap-dancing. My whole mechanism is about charming people. And fixing things that can’t be fixed. That’s why I tell stories: it helps me create order where none exists. So I jiggle stuff around until it makes sense to me and I can see a pattern.”

Maupin’s latest book, the memoir Logical Family, is his first book of nonfiction, yet he brings to it the unique storytelling gifts that have animated his fiction, and he more than delivers on the “tap dancing” that will win his readers’ attention and engagement. Maupin fans will recognize many of the stories and autobiographical details that he shares in this memoir; he’s mined them often for his fiction, particularly in The Night Listener, as well as throughout his nine “Tales of the City” novels, and always to great effect.

He’s equally forthcoming about his encounters with the famous and the infamous, a list that includes Jesse Helms, Richard Nixon, Christopher Isherwood, Ian McKellen, Tennessee Williams, and Rock Hudson. It’s no stretch to describe Maupin’s memoir as “highly anticipated,” and he doesn’t disappoint.

But Logical Family is also a coming out story, and it’s this idea of finding one’s own community (or “claiming truth,” as Maupin phrases it in a prefatory note) that gives the book its title. As members of the LGBT community, says Maupin, we eventually “join the diaspora, venturing beyond our biological family to find our logical one, the one that actually makes sense for us.” Naturally, a good chunk of this memoir focuses on the writer’s biological family, which was Southern and decidedly conservative. There’s even a gothic element, as Maupin explores the mysterious circumstances surrounding the suicide of his paternal grandfather.

Maupin assumes an almost apologetic tone as he describes the roots of his family’s conservatism and his youthful embrace of its politics. Jesse Helms was a family friend, and one of Maupin’s earliest writing gigs was as a conservative columnist for his college newspaper. In fact, Maupin carried the conservative banner all the way to the White House, so to speak. Shortly after his tour of duty in Vietnam—he had enlisted and served in the Navy—he went back to complete a community-building mission, essentially a PR effort, that earned him the admiration of President Nixon and an Oval Office visit. This meeting is captured in a photograph that Maupin later displayed proudly (if ironically) in his San Francisco apartment. (It’s also included in the book). (Years later, historian Douglas Brinkley informed Maupin that his visit was recorded on one of Nixon’s infamous White House tapes.)

It was during his time in the military that Maupin lost his virginity, at the relatively ripe old age of 25. His account of the event is wonderfully honest and unvarnished. He also includes a funny (and perhaps, to many readers, painfully familiar) story about getting crab lice for the first time.

Maupin eventually ends up in San Francisco, and after a few stops and starts he lands the writing jobs that lead to the birth of his famous “Tales of the City” books. For readers who happen to be aspiring writers, Maupin offers stories about just how hard it was to break into writing full time, and how many lackluster jobs he had to endure before he finally found his footing. And for fans of the “Tales of the City” novels, he provides intriguing background on the people who inspired his creation of Anna Madrigal and some of the novels’ other colorful characters.

Perhaps the most enjoyable aspect of Logical Family is reading about those who, to varying degrees, were part of Maupin’s “logical family.” His friends included Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, and Ian McKellen, among others, and he paints an engaging and moving portrait of these relationships. He also describes his romance and friendship with Rock Hudson. What emerges is a poignant portrait of a restless soul who came to an untimely and tragic end. The Hudson-related stories are not without humor, however, especially when Maupin describes his first actual sex with the former matinee idol.

Some of Maupin’s encounters with the famous are very brief, but wonderfully telling, such as the time he unexpectedly found himself offering refuge, and a joint, to a beleaguered Tennessee Williams. Maupin’s logical family is a richly populated one. There are tender reminiscences about a wide array of lovers and friends with whom he navigated San Francisco in the 1970s, and the consequences of the AIDS epidemic that followed soon after.

Over the past couple of decades, the memoir has evolved into a kind of publishing phenomenon. You don’t have to be a former head of state, a movie star, or some other luminary to write your memoirs, but you do have to know how to read the currents of your experience and find within them the particular poetry of your life. Maupin’s storied career has certainly provided him with the raw material for a rich memoir, and in Logical Family, he’s woven it all into an intriguing and beautiful pattern.

Jim Nawrocki, a writer based in San Francisco, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.

Discussion1 Comment

Your review of Logical People has inspired me to get a copy and enjoy Maupin’s memoir. I met him in passing while he lived in Santa Fe, and we knew some of the same people. I am putting finishing touches on my next autobiographical work, A Kaleidoscope: Fragments of Memories over the Decades. Thanks for the heads up.