LOS ANGELES-BASED photographer Jeff Sheng spent much of 2009 up in the air. He flew more than 30,000 miles doing portraits of U.S. service members affected by the controversial “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which is undergoing considerable debate and review in 2010. This very serious artistic endeavor found Sheng; he did not find it.

For the last six years, Sheng has photographed high school and college athletes who are out of the closet, an ongoing project he has titled “Fearless.” The most widely seen exhibition of “Fearless” was at the corporate headquarters of ESPN in Bristol, Connecticut. That show was covered in a feature on ABC World News. “Fearless” is usually displayed in school gyms, where athletes pass by it in droves.

“Having those photographs exhibited in gyms and student centers where the majority of the people seeing them were athletes and straight is important to me. For them, being able to look at these photographs of the community, of all these different types of LGBT-identified athletes and then seeing the artists’ statement about it, makes them think a little bit differently about their perceptions of gay people.”

As “Fearless” gained attention, Sheng began hearing from people all over the country who admired what they saw and wanted to share some of their own stories about their lives in sports and in the closet. He also heard from members of the U.S. military serving abroad: “A few of them actually asked if I had ever considered a project on ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell.’ I found out that a lot of these service members had been closeted in high school and college. Now they were in the military and were older, wishing that they had the freedom to be out.”

Sheng was intrigued by the idea but resisted it at first. “I thought about it for a while. I asked many of them if they would be willing to be in this project and they all said yes. The only problem was that they were all stationed overseas at the time. So I would actually have to have them wait to get back to the U.S.” After a few months, he started hearing from the soldiers, who were ending their tour of duty and offered to take him up on the offer of a photo shoot.

Sheng was intrigued by the idea but resisted it at first. “I thought about it for a while. I asked many of them if they would be willing to be in this project and they all said yes. The only problem was that they were all stationed overseas at the time. So I would actually have to have them wait to get back to the U.S.” After a few months, he started hearing from the soldiers, who were ending their tour of duty and offered to take him up on the offer of a photo shoot.

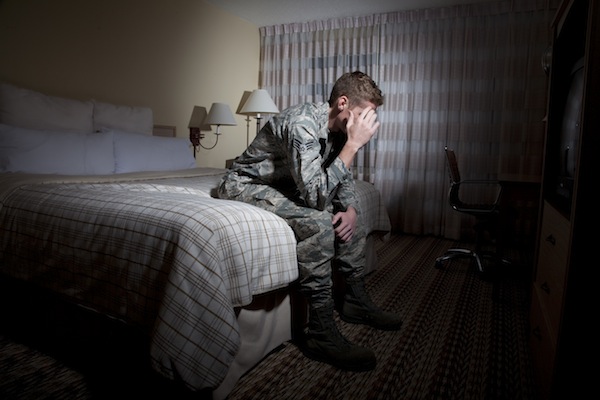

Sheng then faced the challenge of how to do a photographic portrait while not exposing the identity of the subject. As an instructor at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Sheng teaches studio art classes, including the history of photography, so the Harvard–educated artist started to do his homework. “I was looking a lot at portraiture where somebody’s identity was not revealed. I was thinking about portraiture in domestic spaces, such as bedrooms. I was thinking a lot about images that were about exile.” Most helpful to him was Joseph Koudelka’s seminal work Exiles, which showed the devastating impact of Soviet takeovers of various Europeans countries. “Exiles deals with those who had really suffered under the new Communist regime, and the photographs are just heartbreaking. They are very much about isolation, about being cut off from society. And they’re black and white. I’ve pored through this book over and over, looking at the images, thinking about how I could do something similar but using color.” Also, of course, the political elements of Sheng’s project correspond provocatively with Koudelka’s. As Sheng realized, “With ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell,’ you’re in many ways cut off from your peers, your country. You are exiled. You don’t have the freedom to live your life the way you want to live it.”

So, openly gay athletes inspired unwillingly closeted service men and women to come out in this complex way, showing themselves, even as their faces and names are concealed. Being part of this project is a personal and a political act, as Sheng quickly realized. “I got to spend a lot of time with these service members who in many ways have a really positive experience in the photo shoot, in part, I think, because they feel like for once they’re actually being recognized in some way and that this is their way of taking a stand against injustice without ruining their careers.”

A story in Time magazine (Feb. 15, 2010) featured one of the portraits from Sheng’s series. The L.A. Times and The Advocate have printed some of the images, too. He has recently self-published volume one of the project (www.DADTbook.com). A centerpiece in the book is a page with color portraits of the last three presidents; the facing page is an e-mail to President Obama from the email address “Gaysoldiershusband,” who writes: “My partner is currently serving in Iraq, and in a situation where he is under fire on a daily basis. … The day he deployed, I dropped him off far from his base’s main gate, and he walked alone in the dark and rain to report for duty. When the rest of his buddies were surrounded by spouses and children at mobilization ceremonies, he stood by himself. … I am not sure if I can adequately convey the mixture of fear, pride, heartache and hope I feel. … I ask you to consider relieving the burden of fear and dishonor from brave men and women who risk being punished simply for whom they love.”

For Sheng, too, all of his work is personal and political. He is an athlete, having won a gay tennis tournament in Indianapolis in the summer of 2009, as well as participating in the 2009 Gay Games in Copenhagen, where “Fearless” was exhibited as part of an LGBT Human Rights conference. He has recently returned from the Winter Olympics, where an installation from “Fearless” was on display at Pride House in Whistler and in Vancouver, the first-ever LGBT space geared to athletes and spectators at an Olympic venue. In reflecting on why he focuses so much on these issues, Sheng says, “As a second-class citizen in this country, I have no choice but to make work that tries to make progress in terms of my equality. I cannot exist as a human being in America right now knowing that I do not have equal rights and not do anything about it. I can’t sit by and watch injustice happen.”

Jeff Sheng is a young artist with a vision and a purpose. Reflecting on his training and his inspiration to become a photographer, he realized that the most vivid images most of us have of the Civil Rights movement or the Vietnam War are photographs. The still—the moment frozen in time—can have a powerful, harrowing, lasting impact. Observes Sheng: “With photography, you only need a split second to put an image in front of somebody for them to begin to think about it in a way that could begin the process of changing somebody’s mind about something.”

Chris Freeman, co-editor of Love, West Hollywood: Reflections of Los Angeles, teaches at the University of Southern California.