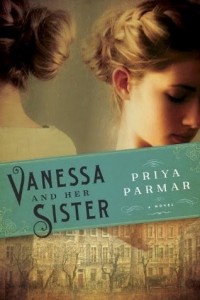

Vanessa and Her Sister

Vanessa and Her Sister

by Priya Parmar

Ballantine Books. 350 pages, $26.

The descendants of the original members of the Bloomsbury Group—a name taken from the neighborhood in which they lived, not coined until the 1960s—are very much among us. Earlier this year, Van Gogh: A Power Seething, by Julian Bell, a painter and writer who’s the grandson of Vanessa Bell (and great-nephew of Virginia Woolf), received front-page coverage in The New York Times Book Review. Vanessa and her younger sister Virginia are the eponymous title characters of a wonderfully appealing and compulsively readable novel by Priya Parmar. It’s told with style and authority by a writer with just one previous book to her credit, a historical novel about actress Nell Gwynn.

Parmar’s narrative relies for the most part on an imagined diary kept by Vanessa Bell from 1905 to 1912. Before her marriage to Clive Bell, Vanessa had been, in real life, a student of John Singer Sargent at the Royal Academy School and an admirer of Whistler’s works. In an almost throwaway comment on the pitfalls of fictionalizing such a well-documented group of people, Parmar writes in an introductory note: “For me the difficulty came in finding enough room for invention in the negative spaces they left behind.” To say that she channeled Vanessa Bell would be facile, but her depth of scholarship and obvious deep regard for the members of the Bloomsbury Group are apparent.

In 1905, Virginia and Vanessa’s beloved brother Thoby Stephen, along with friends he had met at Trinity College, Cambridge, moved back to London. Among them were Lytton Strachey, Clive Bell, and Leonard Woolf. They held weekly salons to discuss art, literature, and politics. At first, the sisters were the only women invited. They would frequently meet outside their salon, in various permutations, sometimes traveling together, sometimes forming passionate, platonic—or even romantic— friendships, regardless of gender or assumed sexual orientation. Strachey is quoted (in the fictional diary) as saying: “We all love in triangles.” The diary frequently veers off into extensive dialog that few diarists would ever be able to replicate exactly. There’s much tragedy, too, in Thoby’s 1906 death (from typhoid, contracted in Greece). “Did you wake up in time to see your last morning?” Vanessa’s diary entry wondered on the day he died.

Parmar creates tremendous tension around the many emotional illnesses that Virginia Woolf endured: “A few years ago, Virginia talked for three days without stopping for food or sleep or a bath. … [Her] words unraveled into elemental sounds: quick, gruff, guttural vowels that snapped and broke over anyone who tried to reach her. Her features foxed with anger growing sly and sharp. … [She] spent a month in the nursing home recovering.” Vanessa’s husband, Clive Bell, and Virginia may or may not have had an affair. (Strachey was quite sure there was nothing going on. “It is your attention she’s after, not his,” he told Vanessa.) Soon, Vanessa found herself involved with the British artist and critic Roger Fry, whose wife was permanently institutionalized for mental illness. Fry, who “galvanized Bloomsbury,” in the words of Richard Shone, author of Art of Bloomsbury (the catalog for a 1999-2000 Tate exhibit), was an acclaimed art critic, writer, and artist.

At one of the Bell’s innumerable house parties, E. M. (“Morgan” to his friends) Forster, just a couple of novels into his writing career, makes an appearance. “Morgan goes about his writing with such an unfussy, self-effacing grace that he is one of the few people for whom Lytton feels no real jealousy, only admiration.” Virginia Woolf, a regular contributor to The Times Literary Supplement, “is bitingly jealous of Morgan and usually avoids discussing his novels.” It bears mentioning that the artists and critics of Bloomsbury started to make their mark before Woolf’s first novel, The Voyage Out, was published in 1915. Between 1911 and ’12, Vanessa had made four portraits of Virginia, who felt overshadowed by the artists’ success and was annoyed that art talk took precedence over literary talk.

Interspersed among the diary entries are imagined postcards that Lytton Strachey sent to his friend Leonard Woolf, who in real life, and in Parmar’s creation, was employed by the Ceylon Civil Service. Many of the postcards urge Woolf to come back to England and to marry Virginia Stephen.

An occasional 21st-century anachronism does creep in, and Vanessa has the rather annoying habit of ending some of her diary entries with a cliff-hanging paragraph beginning with the word “And.” One such entry is about “Maynard Keynes, Lytton’s young economist friend from Cambridge—with whom I understand him to be occasionally involved? But then, I may be wrong. I often am.” Parmar provides a helpful “What became of them” section that can lead readers to the original works by the authors, to their biographies and memoirs, and to the art museums that hold their works.