Editor’s Note: The following piece is excerpted and adapted from the pages of the author’s forthcoming book, “We Met in Paris”: Grace Frick and Her Life with Marguerite Yourcenar, to be published later this year by the University of Missouri Press.

IN JANUARY 1981, I was preparing for my doctoral oral exams in French literature at the University of Connecticut when The New York Times Magazine ran a lavishly illustrated article on the imminent induction of a woman—the first one in 350 years—into the Académie Française. That woman was Marguerite Yourcenar, author of such distinguished works as Mémoires d’Hadrien (Memoirs of Hadrian) and L’Œuvre au Noir (The Abyss). I also learned, astonishingly enough, that she was living on an island in my home state of Maine with her American companion, Grace Frick. One question I undoubtedly would be asked at my orals was on what or on whom I planned to write my dissertation. I knew immediately upon reading Mémoires d’Hadrien what the answer to that question would be.

Over the following months I read everything of Yourcenar’s that I could get my hands on, finally zeroing in on the subject of “sacrifice” in the French author’s novels and plays. After a brief exchange of letters in the summer of 1982, Mme Yourcenar graciously allowed me to come speak with her in person. On August 17, I found myself knocking on the door of her home, “Petite Plaisance,” in the Mount Desert Island village of Northeast Harbor. I arrived with piles of notes, hoping to show that I had found the key to her work. I soon realized that Madame, as she preferred to be called, would not be easy to convince. Sacrifice had a role in her works, to be sure, but in her view not a terribly important one. So we spoke of other things, laying the foundation of a friendship.

At about the same time, Mme Yourcenar began handing me pages she had just finished drafting of projects she was working on that summer. The first batch was the beginning of an essay collection about her recent trip to Japan (later published as Le Tour de la Prison, 1991). Because I was not an Orientalist, she wondered whether I would find the content accessible. Each typed page was festooned, as I wrote in my diary at the time, with “taped fragments of pages, as one might piece together disparate fragments of an antique statue.” More drafts came my way, including an essay that speaks poignantly about her last travels with Frick. It was a thrill to read and comment on Yourcenar’s writing, something that Grace Frick had done over the course of many years, I learned—and did so with a sharp editorial eye that I did not possess. But I did eventually work with Mme Yourcenar on a few translation projects, which gave me an idea of what daily life must have been like at Petite Plaisance before Grace died.

Ten years later I would translate Josyane Savigneau’s Marguerite Yourcenar: Inventing a Life (1993) into English. The release of that book brought me a letter from one of Mme Yourcenar’s oldest and closest American friends, Paul Minear, a retired professor of theology at Yale Divinity School and a highly regarded New Testament scholar. He and his wife Gladys had known Grace Frick since 1931, when they were the host and hostess of the women’s graduate residence at Yale. It was they who first brought Frick and Yourcenar to Mount Desert Island in 1942, where the two women would eventually take up permanent residence. Paul Minear saw much that was good about the Savigneau biography, and he was grateful for it.

Nevertheless, his primary reason for writing was to express his distress at the book’s “grossly unfair” depiction of Yourcenar’s American companion. Savigneau’s biography presents Frick as a controlling figure who dominated Yourcenar, forcing her to remain in the U.S. after World War II ended rather than return to Europe. At the same time, paradoxically, Savigneau treated Yourcenar’s partner of more than four decades as a peripheral figure. Minear emphatically protested this assessment in his letter’s final, passionate paragraph: “The bonds between the two friends were so strongly rooted in intellectual, psychological, societal and spiritual affinities that they created together a single life. … Their mutuality in living was so authentic that this book should have been a biography of Marguerite Yourcenar and Grace Frick, with a subtitle: Inventing a Single Life.”*

Jean Hazelton, another close friend of Frick and Yourcenar, was similarly disturbed by the portrayal of Frick in the Savigneau biography. Hazelton and her husband Roger had met the two women in the early 1950s. In November 1993, Hazelton sent her thoughts about Inventing a Life to Gladys Minear. Her reaction to the work was so intense that she found it hard to write coherently. “I resented the author’s belittlement of Grace in almost every reference to her,” she begins. “She is made to seem a silly American.” Hazelton is further offended by the use of “such words about her as maniacal, fits of passion, indignant, shocked, eccentricities, etc.” Like the Minears, the Hazeltons had known Grace and Marguerite for decades. They had dined, attended plays, and taken trips with the couple in France, had stayed with them on several occasions at Petite Plaisance, and hosted them at their own homes in Massachusetts and Maine. They remained in touch until Grace’s death in 1979 and Marguerite’s eight years later. But in reading the Savigneau biography, Hazelton wrote: “at times I thought I was reading about strangers whom I had never known.”

Nor was it only Grace and Marguerite’s old friends who found tendentiousness in Savigneau. Stephen Goode of the Washington Times (Oct. 31, 1993), for example, wrote skeptically: “In a very French manner, the author lacerates America. Yourcenar, though born in France, chose to live most of her life on Desert Island [sic]in Maine with Frick. But this wasn’t a happy time for her, according to the author, because Yourcenar was living in a country ‘without civilization,’ and which she could endure only with the greatest pain.” Publishers Weekly noted that Savigneau “simply cannot believe this practitioner par excellence of the French language would want to live in the U.S.—or, for that matter, with Frick. Savigneau does not present convincing evidence for the oft repeated thesis that Yourcenar, tough though she decidedly was, was bullied by Frick into staying in the U.S.” And L. Peat O’Neil observed in her witty Belles Lettres review (Issue 9.3, 1993-94), titled “Invent Your Life—Lest Someone Beat You to It,” that Savigneau “creates a tension between the two principals that I did not find in the supporting quotes. … Furthermore, the character painted so adroitly in early chapters would hardly put up with a destructive partnership or be held hostage by guilt. A woman willing to do legal battle with the powers of French publishing hardly needs 50 ways to leave her lover.”

Despite these critiques, once Savigneau had laid the groundwork, subsequent biographers and commentators mostly built on that portrayal of Frick, some of them even upping the ante.** Perhaps it is true, as Janet Malcolm aptly notes in her fascinating Two Lives: Gertrude and Alice (2007), that the biographer’s single-minded focus on his subject “blinds him to the full humanity of anyone else.” But when two lives are as intimately entwined as those of Frick and Yourcenar, there comes a point at which the disparagement of the one yields a distorted portrayal of the other.

Marguerite Yourcenar was never one “to spill … my emotions in public,” as she told Cathleen Medwick of Vogue magazine in November 1982. Though she believed deeply in the need for all-encompassing sexual liberation, she did not take a strong public stand against the oppression of gays and lesbians as she did, for example, against racism, the Vietnam War, destruction of the natural environment, and animal cruelty. She always tried, as she said in With Open Eyes: Conversations with Matthieu Galey (1980), “wherever relations with other human beings who really mattered were concerned, whether lasting or brief, intermittent or continuous … to keep them in the shadows that conform so well to the important things in life.”

I would be remiss, however, if I failed to acknowledge that Yourcenar herself is at least in part to blame for biographers’ negative perceptions of Frick. Although she often spoke of her companion with admiration, tenderness, and gratitude in the years after Grace’s death, she also made a number of dismissive comments about her, both publicly and privately. One almost gets the impression that Yourcenar was determined not to sentimentalize her relationship with Frick at all costs. This resolution seems to run parallel to her desire not to express self-pity over the fact that her mother, Fernande de Crayencour, had died of complications related to Marguerite’s birth. Joan Acocella picked up on one of Yourcenar’s trivializing remarks in her New Yorker article (Feb. 14 and 21, 2005), writing that “when she was old, she said that her passion for Grace exhausted itself after two years.” Of course, there were difficulties, conflicts, and struggles for control. What intimate partnership lacks them? But there was also affection, harmony, joy—and, yes, passion of all kinds. If we look not at what Yourcenar sometimes would say after Grace was gone but at the couple’s trajectory as it evolved, we get a more nuanced, and more accurate, view. The romance did not in fact exhaust itself after two years; it was part of the women’s everyday life.

In the months before she died, Yourcenar was working on the semiautobiographical Quoi? L’Éternité. In the later pages of that unfinished work, she recalled “unforgettable moments” from a long-ago trip to England, a country to which both she and Grace were deeply attached. “In my mind’s eye,” wrote Yourcenar, describing one of those moments, “I see a young woman, with a young Sibyl’s features, sitting on one of the gates that separate the fields from the pastures over there; we’re at the foot of Hadrian’s Wall; her hair is waving in the wind from the mountaintops; she seems to embody that expanse of air and sky.” That young Sibyl probably did not possess the ancient prophetess’s gift to tell what lay ahead; but the aged author, looking back, clearly saw what lay behind, and, in one of many guises, it was love.

* Paul Minear, letter to the author, December 22, 1993. At the top of this three-page, single-spaced typewritten letter, Minear indicated that the document was “not for publication.” I obtained permission to quote from it only what I’ve quoted herein when I interviewed Paul and Gladys Minear, April 5–6, 2004.

** Three other biographies include Michèle Goslar, Yourcenar: “Qu’il eût été fade d’être heureux” (Brussels: Racine, 1998 ; rev. ed., 2014); George Rousseau, Yourcenar (London: Haus, 2004); and Michèle Sarde, Vous, Marguerite Yourcenar: La Passion et ses masques (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1995).

Joan E. Howard, director of Petite Plaisance in Northeast Harbor, ME, is the author of the forthcoming Grace Frick and Her Life with Marguerite Yourcenar.

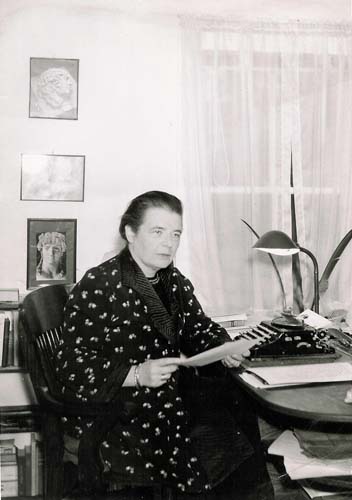

Mme Yourcenar in Maine

0Published in: March-April 2018 issue.