New Museum, New York City

Sept. 27, 2017–Jan. 21, 2018

SINCE ITS FOUNDING fifty years ago by my friend and colleague Marcia Tucker, New York’s New Museum has mounted many novel exhibitions. Trigger: Gender as a Tool and a Weapon is no exception and heralds things to come in contemporary art. Curated by Johanna Burton, the exhibition is accompanied by a copiously illustrated catalog that includes essays and conversations with participating artists. The unifying theme of the exhibition, if one can be found, is the deconstruction of sexist, racist, homophobic, patriarchal institutions from the 1960s to today.

The critical problem with Trigger is that it mainly echoes Dada and Surrealism in presenting obvious outrage. Glamorous, demented, grotesque, silly, monstrous, clichéd, and campy, the exhibit gushes extravagantly in a display of hundreds of mixed-media works by over forty artists, mostly younger artists intent on critiquing today’s society and culture in a typically postmodern fashion. It demonstrates the extent to which many of today’s bright young things could learn a lot from activist artists of the past.

Trigger is a scattershot show full of hits and misses, cheap shots, and wannabe big shots. It asks the question: how can art serve two masters, social justice and art itself, without turning into propaganda? Works are spread out from the fourth floor all the way down to the museum basement and cover artists working across scores of mediums and genres: film, video, performance, painting, sculpture, photography, and craft. Advancing no single point of view, the exhibition brings together a wide range of practitioners, some with a longstanding commitment to activism, others who have recently entered the fray.

One recurring target of Trigger is the binary, heterosexist, racist, white male patriarchy that rules society, and its failure to deliver on the promise of a better deal for everyone. It is a compilation of today’s ills that will cause some to shudder, others to scratch their heads, and still others—those familiar with contemporary feminist art from the 1970s—to ask, haven’t we been here before?

The inclusion of a few smart, savvy artists of yesteryear helps to broaden the frontier. Still, the question of what is “normal” regarding masculinity and femininity, however vexing, is pretty old territory. After going through the entire chaotic show, I concluded that the younger generation is mostly standing on the shoulders of earlier feminists and queer artists who tried to take us beyond binary (or other) classifications at a time when it was risky to do so. I think of Jackie Jackson and the Jewel Box Revue and other drag shows and female impersonators, of shows that were actively political, referencing gender fluidity and challenging heterosexism long before these younger artists were born. I think of Charles Ludlam’s 1983 farce Le Bourgeois Avant-Garde, a comedy after Molière performed by the gender-bending Ridiculous Theater Company at One Sheridan Square. Ludlam’s play, a satire on the downtown New York art scene, is as relevant now as it was then.

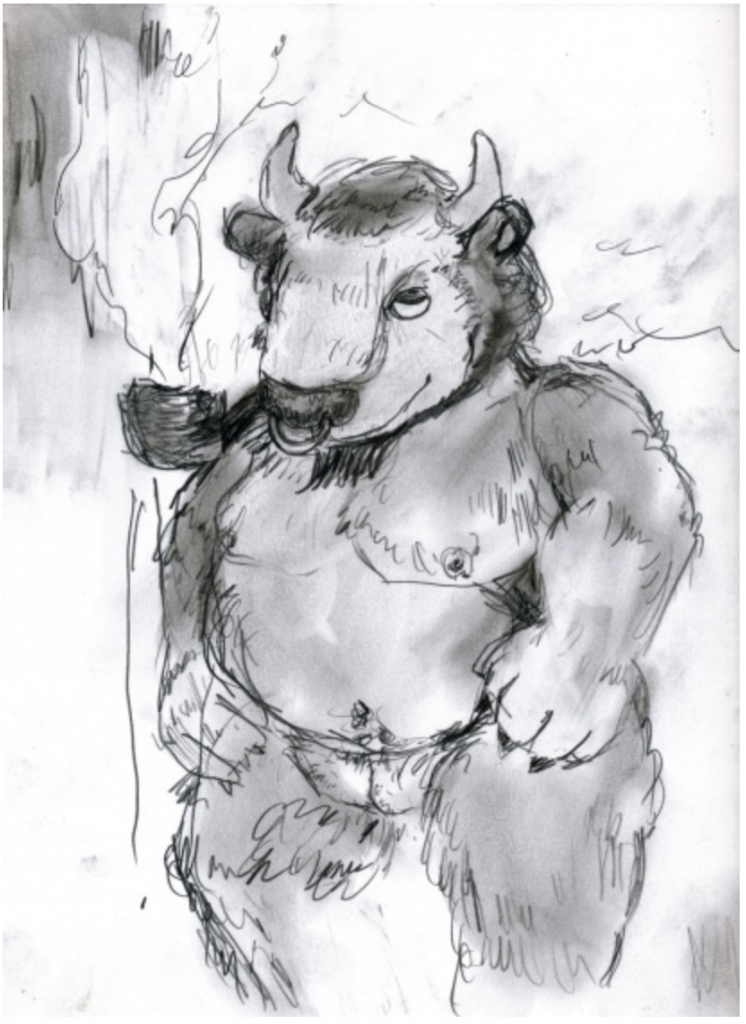

For all my criticisms, the organizers of Trigger can be commended for including contributions by pioneering artist Nayland Blake, whose “fursona” is hybrid bear-bison “Gnomen,” who playfully morphs into a different species and gender right before our eyes. Here the artist spoofs the preference for furry partners among gay men and performs as Gnomen, giving free hugs to his audience. Elsewhere in the exhibit, appearing onscreen are the deceased members of the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, including Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson at the Stonewall Riots. Johnson, a black transgender woman, participated in Ludlam’s plays, and her inclusion here pays homage to the activism of an earlier generation.

Commissioned performances figure prominently in the exhibition, such as a work by AIDS activist Gregg Bordowitz titled Only Idiots Smile (2017). Wu Tsang’s film Girl Talk (2015) plays on a loop in a separate gallery and captures poet and theorist Fred Moten (also a curatorial adviser to the exhibition), bejeweled and shrouded in velvet, twirling and gesturing at the camera in a sun-spotted yard while Josiah Wise’s cover of the jazz standard “Girl Talk” plays.

Among the more interesting works are those by Tschabalala Self and Vaginal Davis. Self, working in traditionally female-associated media, stitches racially and sexually ambiguous figures from patches of fabric on canvas. Davis’ Proper Butch Goddess Freya (2015) presents a violently ripped image—made with raw, red neon nail polish purchased from the beauty supplies section of a dollar store—depicting female genitalia. A series of these is arrayed horizontally along the museum’s wall like bleeding scarlet gashes cut across a long history of sexism in which women have been reduced to their usable organs.

Trigger ends up being a mildly provocative carnival comprising everything that was and still is on the streets of New York City. It harks back to a time when sexual freedom could be expressed in any form you wanted it to take, and birth control pills allowed women to embrace their desires as freely as men. It reinterprets the ethos of Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground and the bathhouse urbanites who provided Bette Midler with her first audiences, along with Andy Warhol’s Factory and, later, grunge culture. These were some of the engines of creativity that ran the spectrum during the period covered in this show.

Trigger calls to mind pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s comment that he wanted an art “that does something more than sit on its ass in a museum.” The New Museum’s curators have pulled the trigger; now it is up to the viewers to decide which ones hit their mark and which ones miss—or, to return to Oldenburg’s metaphor, which ones will get off their asses and stay with us even after we leave the museum.

Cassandra Langer is a freelance writer based in New York City.