Under My Skin

Under My Skin

by Orville Lloyd Douglas

Guernica Edition. 80 pages, $15.

Haiti Glass

Haiti Glass

by Lenelle Moïse

City Lights/Sister Spit. 79 pages, $10.95

The Road to Emmaus

The Road to Emmaus

by Spencer Reece

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

124 pages, $24.

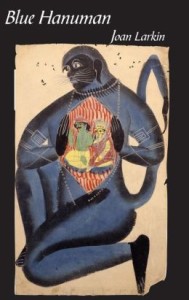

Blue Hanuman

by Joan Larkin

Hanging Loose Press. 78 pages, $18.

ORVILLE LLOYD DOUGLAS concludes his latest book Under My Skin with the lines: “My thoughts will be a sledgehammer to smash the doctrine of my oppressors/ I would murder millions if my words could kill.” Even if we put aside the stale image of the sledgehammer, we are faced with two problems of activist poetry: first, that poetry is not a very good sledgehammer for smashing doctrines; and second, that you have to believe that conditions are capable of changing in order to arouse people to act. Murdering millions undoubtedly would change the world, but even that threat is undercut by Douglas’ awareness that words don’t kill.

The most moving and fascinating portion of this book is a section titled “Vick,” a sequence of poems about a failed love affair between Douglas, who is black, and Vick, who is Sikh. Vick is unwilling to give up his family and his heritage to live with Douglas. Instead, he marries and fathers children. Douglas is able to convey his love, anger, sadness, and resentment in a complex mixture. In the poem “Touch Me,” he orders his interlocutor to “touch me, but not with your hands,” and also to “soothe,” “hold,” “speak,” “see.” It concludes with the order: “Believe me: I do love you.” The speaker of the poem doesn’t do anything; all the actions are demanded of the beloved. But what strikes me is that the demand to believe already suggests disbelief, and that disbelief is heightened by the strained “I do love you,” which sounds as if Douglas is trying to convince himself. It is a not-quite love poem, in which Douglas tries to silence his own doubts. Still, these doubts are far more interesting than his efforts “to expunge all the negativity out [his]hole” whenever he thinks of Canada on the toilet.

Whereas Douglas thinks of Canada when he flushes, Lenelle Moïse must confront a much greater horror: what has happened to her nation of origin, Haiti. For Haiti has been shaken until it broke apart and then drowned in one natural or political disaster after another. She is angry for and at a country that has been subject to “embargoes, exploitation/ stigma, sabotage, scalding/ doubt,” yet she retains the hope that much can be done to ameliorate these conditions and asks people to join her in the “much more to do.”

Moïse feels more guilt than anger, not only for escaping Haiti’s disasters of the last few years but also for causing her parents to suffer as they provided her with the opportunities available only in the U.S. In her prose poem “The Children of Immigrants,” she describes the sacrifice her mother endured to protect her from the violence of the ghetto where they lived. Her mother, however, proves to be more than protective, showing a support for her daughter’s sexuality that is atypical. In “Madivinez,” one of the best poems, Moïse calls her mother to find out the Kreyol term for lesbian, which does not appear in her Kreyol-English dictionary. Her mother tells her the word is madivines, but warns her that “it’s vulgar/ [a word]no one wants/ to be/ called.” Nevertheless Moïse embraces it with her “holy, haitian dyke heart.” This is a book that prays for the children but asks “first/ teach them/ to play.”

Spencer Reece is an Episcopal priest. This fact explains some of the quiet, ruminative authority of his voice. But underneath his disciplined calm there’s an anger so barely contained that I found it impossible to trust these poems or to get close to them. They are like the beautiful tabby that rubs up against you and then bites you when you try to pet it.

The clearest example is the prose poem “Margaret.” Margaret is a survivor of the Holocaust who lives with the guilt that the man whom she paid to escort her father safely out of Hungary took the money and placed her father “on a train to Auschwitz.” How Margaret survived the war we are not told. We get the enigmatic news that she had a husband, “but during the war they were separated in the chaos of Budapest, and later she lost track of him.” This little barb at her loyalty to her marriage is followed by a suggestion of her vulgarity when she has to add that The Cherry Orchard is by Chekhov. But the claws really come out at the end, and they are directed at readers. As if the poem were a travelogue and we were bidding goodbye to Bali, he tells us: “As you leave Margaret behind and turn the page, listen as the page falls back and your hand gently buries her. This is what the past sounds like.” What are readers to do? We’re cruel if we turn the page; we’re inattentive if we don’t. Why are we blamed with burying her (even if gently)? How did we become the agents of history? And where is Reece’s responsibility in all this? I felt used by this cheap little guilt trip.

The title poem plays a similar trick. It’s about his relationship to Durrell, his sponsor in AA, a former Harvard student and closet homosexual filled with snobbery and self-hatred. But Reece wishes to tell that story as part of his therapy with Sister Ann, a Franciscan. I’m not at all clear about Reece’s problem with Durrell, who seems a perfectly unlikeable person, but somehow Sister Ann gets blamed for terminating the therapy because her order has relocated her. As Margaret lost track of her husband, so, too, Reece “lost track of Sister Ann.” Indeed the book is a tale of lost connections, or knots never really tied, an angry, drifting narrative in which we are dared to turn the page.

Joan Larkin’s new book takes its name from a painting, “Bought for a few annas,” depicting the Hindu monkey god Hanuman ripping open his chest to reveal Rama and Sita, the perfect ruler and wife, hidden inside him. It is a fitting emblem for a book concerned with finding the human hidden in the animal, the spirit stuffed within the body, the past burrowed in the present and vice versa. Finding these hidden properties requires both delicacy and determination. They do not show themselves without pain. The poems—all short, most in one stanza—are like hard seeds that need to be cracked and ground. For example, in “eye,” a strange underwater arctic beast some of whose legs “eat what blooms/ between ice crystals” speaks to us only after we have sent our camera down “six hundred feet/ under the ice shelf.” Sometimes we get there almost too late, as in “The Porch” in which Larkin observes a spider producing a “shining dome” out of her “small steel body” to preserve the corpse of a moth caught in her web.

All animals live on other life. Their survival requires the death of other living beings. The ravages of life are ravishing in these poems. “Wendell Seal,” one of the simplest and most extraordinary poems in this marvelous collection, issues from the voice of the seal who “fell from sealmother’s/ liquid womb into fast-ice/ and she suckled me with her thick/ milk and kept me, fifty days.” It ends fifteen lines later with the seal old and toothless, the prey of other predators, aware that “sea-stars, worms, and flesh-eating/ amphipods will slowly cover/ me and devour my meat.” Until then, she remains “standing in the wind,/ seal flesh still warm.” Now in her seventies, Joan Larkin is a poet used to standing in the wind, but her flesh glows with primordial heat.

David Bergman is a poet and professor of English at Towson University. He is the poetry editor for this magazine.