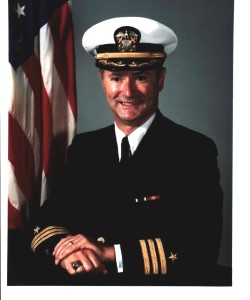

THE YEAR WAS 2005, and on a lovely fall weekend some 400 people, including spouses, gathered at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapo- lis on the occasion of their 45th class reunion. The four-day affair included a formal dinner dance, a Navy football game and a memorial service. Robert M. Walters, a retired U.S. Navy engineering duty officer, was among the distinguished alumni attending. Walters had graduated third in the Class of 1960 out of 797 mid- shipmen. (Two years earlier, Sen. John McCain famously fin- ished fifth from the bottom of his class.) Walters received a doctorate from MIT in Naval Architecture and Marine Engi- neering and went on to help design nuclear submarine fluid sys- tems for Adm. Hyman Rickover, the legendary “Father of the Nuclear Navy.”

But the reunion would also prove a personal moment of truth. At 68, Walters would not be returning to his alma mater as Robert but rather as Robyn Marie Walters, a transsexual woman. Six years earlier, Robyn alerted her classmates about her sex change with a brief news item in the alumni magazine. But this was the first time she would come face-to-face with many of her former classmates for an extended period of time. With the Navy still very much a macho environment, Robyn could not be certain what her reception would be like. Would there be stares and whispers, curiosity and gossip? Would her classmates feel uncomfortable? Would she?

The formal dinner was held in a reception hall at the Navy Marine Corps Stadium, with guests seated by companies at ta- bles of ten. Most of the men wore tuxedos or dark suits, with the women attired in evening gowns and cocktail dresses. Nails freshly manicured, wearing some light makeup and red lipstick, Robyn showed up in a simple spaghetti-strap, black mid-length evening dress, accented by pearls and pearl earrings.

Amid the clatter of cocktail glasses and the buzz among guests before dinner, there was surprisingly little reaction from the crowd, save one incident when she was introduced as “Robyn” to another classmate. “This fellow’s jaw literally dropped, but he recovered well and shook my hand.”

Anyone who looked at Robyn’s hands would have found an- other surprise. In addition to her class ring on her right ring fin- ger and favorite pinky rings on both hands, she was also wearing engagement and wedding rings given to her by her hus- band Emery, who also happens to be a transsexual. In the best romantic tradition, the two were married on Valentine’s Day in 2000, in a ceremony held in Port Townshend, a small town fifty miles northwest of Seattle. Today, the couple live a quiet life, having relocated from Washington State to Maui.

The two had much in common, having met late in life— Robyn was 62 and Emery, 56—over the Internet, no less. Both had previously been married—twice. Both had four children, all now fully grown. And, of course, both had gender identity is- sues. Robyn had sexual reassignment surgery (SRS), going from male to female (M/F). Emery, born Carol Ann Forde, had been a wife and mother before deciding to have SRS to become a man (F/M).

What are the Odds?

The number of transsexuals in the U.S. and around the world is a question on which there is little consensus among experts. Some view it as a gender disorder, others as simply a gender variation. Sampling issues, imprecise definitions, and various biases all contribute to the problem. The American Psychiatric Association estimates that roughly one per 30,000 adult males and one per 100,000 adult females seek sex reassignment sur- gery, and these are the figures most often used by the media. But other experts strongly disagree, among them Lynn Conway, an engineering and computer science professor emerita at the Uni- versity of Michigan, who is also a noted researcher, activist, and herself a transsexual.

Prof. Conway charges the APA figures grossly under-report the numbers. “Can’t psychiatrists count?” she asked in one paper. Based on her research, Conway estimates that “at least one in 500 of those born male now seek to transition, including completing SRS” and “at least some number larger than one in 1,500 of those born female now seek to transition, including completing SRS.” But even if we accept Conway’s estimate, the number of transsexuals relative to the total population is quite small, while the number who have fallen in love is un- doubtedly smaller still. “Unusual perhaps, and fairly rare,” says Robyn, who has read widely on the subject and is also an ac- tivist. “If the odds of being transsexual are one in 10,000, then the odds of husband and wife both being transsexuals should be about one in 100,000,000, meaning about three such couples in America, says Robyn.”

With the greater tolerance toward gays and lesbians has come a softening of public attitudes toward the transgendered generally—what with the benefit of more knowledge on the part of doctors, health care professionals and other experts, more surgeries being performed, changes in the media coverage, and greater visibility by transgender people. In 2011, the Public Re- ligion Research Institute, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research and education organization, released a report that showed that an overwhelming majority of Americans—89 percent—believe that transgender people deserve the same rights and protections as everyone else; and three-quarters (74 percent) favor the expansion of federal hate crime laws to include crimes committed on the basis of the victim’s gender, sexual orientation, or gen- der identity, compared to only 22 percent who opposed.

These changes have been reflected in the popular culture as well, in the form of books and movies that treat the transgen- dered more favorably than in the past. Examples include: the book She’s Not There: A Life in Two Genders, by Jennifer Finney Boylan; the film Boys Don’t Cry (2003); the film docu- mentary Becoming Chaz (about Chaz Bono); the TV drama

Normal on HBO; the play (later a film) Hedwig and the Angry Inch; and dozens of TV talk shows. A body of literature on the topic has emerged with titles like Gender Outlaw (by Kate Bornstein), Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman (by Leslie Feinberg), Sex Changes: The Politics of Transgenderism (by Patrick Califia), and Mom, I Need to Be a Girl (by Just Evelyn).

Toward the end of 2010, a new magazine called Candy, aimed at the transgender community, seemed to catch the spirit of the times. The cover featured an arresting color photo of actor James Franco who, in a compassionate nod toward gender non- conformists, was shown playfully vamping in drag—a haughty dominatrix in a dark power suit, complete with bright red lip- stick and heavy eye makeup. This kind of gender-bending, media-grabbing event prompted William Van Meter to declare in a New York Times “Style” piece (Dec. 8, 2010) that the year 2010 would “be remembered as the year of the transsexual.”

Amid all these stunning changes, however, a question arises: what about transgender people over fifty years of age, like Robyn and Emery Walters, who grew up in the pre-Stonewall Rebellion era when it wasn’t okay to be gay—or certainly trans- gender—back when poodle skirts were all the rage for girls, long pants were a symbol of a boy’s manhood, and marriage was forever? Their story is important because it crosses that great cultural divide of the 1960s and ’70s, taking us back to a time when transgender people were deeply imprisoned by the constraints on gender roles in general.

Gender In the 1950s

Maui, with its gorgeous sunsets and scenic views, is a won- der, even in January. And here the Walters make their home in a modest 640-square-foot, one-bedroom condo, crammed with books, memorabilia, and comfortable furniture. Nice, but a far cry from all the fast-track “Maui Millionaires” on the island. Crisply dressed in a medium-blue matching top and Bermuda shorts, Robyn could have been any seventy-ish, bespectacled, proper-looking lady, attracting no notice in a crowd. Emery arrived a bit later, having been out hiking and taking photo- graphs in the small woods near Black Sand Beach in Makena. Slight of build, wearing a baseball cap, beige shirt and long pants, Emery seemed even less likely to stand out. In conver- sation, he was the more reserved of the two. While Robyn often called her husband “sweetie” and “honey,” Emery avoided such endearments.

Except for gender issues, neither of their early lives was terribly eventful. Carol Ann Forde (Emery) was born in East St. Louis, the youngest of two daughters, and came from a family of modest means. Robert (Robyn) was born and raised in New Jersey, the only child of a non-degreed engineer and his wife. Growing up, he was a nice, quiet Catholic boy, whose mother went to church on Sunday and whose father was an agnostic.

Very early on, both little Carol and Bobby knew they were different. “At age five, I knew I was a cowboy and not a cow- girl,” Emery recalls. Throughout her school years, Carol’s gen- der conflicts were ever-present. One journal entry written many years later notes she was “devastated at having to dance the girl’s part in the minuet in ballet class, while some kid named Marie who was taller, got to dance the boy’s part.”

Once, as a nine-year-old boy, Bobby wandered into his par- ents’ closet when no one was home and put on one of his mother’s dresses. “I forget what it looked like, but it had a silky lining, and a wonderful fragrance.” But when it fell off the hanger, panic set in and he ran out of the room. It was the little boy’s first cross-dressing experience. There followed a pattern in which he would amass a cache of lingerie, only to be over- come with guilt and dispose of it in toto.

Confusion and conflict continued to mark both of their lives. Both embarked upon a desperate but fruitless search to align their physical anatomy with their gender identity. But both ul- timately succumbed to the rigid cultural standards of the time, which ordained marriage and motherhood for Carol (Emery), career and family for Robert (Robyn). “At fourteen,” Emery says, “I decided I would pretend to be the best woman I could be. I married when I was seventeen and pregnant, even though I had a shameful secret.” This marriage lasted seventeen years and produced three daughters, ending when her husband asked for a divorce.

Fearing she might lose her kids, she jumped all too quickly into a second marriage, later giving birth to a son. In time, how- ever, the family fortunes declined in the face of her second hus- band’s heavy drinking and mounting money problems. Facing eviction and shut-off notices, hubby Number Two hightailed it out of Phoenix, where they had been living, leaving Carol and her seven-year-old son to fend for themselves.

Not one, but two marriages had fallen apart. Well into her forties now, she and her young son moved into her sister’s house in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Fortunately, Carol’s big sister was sup- portive—giving financial support which enabled her to get a de- gree from Concordia, a small Lutheran college. But after she lost a part-time county job in 1999, her sister, who had a grow- ing family of her own, asked her to move out. Broke and alone at 56, Carol found herself living in subsidized housing in Ann Arbor with other residents, many of whom were elderly, dis- abled, or drug-addicted. With kids gone, no real job skills, bouts of depression, and huge credit card bills, she concluded: “That’s when I could not tolerate living life as a female any longer. That’s the point at which many MTFs put the gun in their mouths. I didn’t care what happened to me.”

Robert had an easier time of it, relatively speaking. As a stu- dent who loved science, coupled with the promise of a free ed- ucation, he enrolled in the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. But despite an exemplary academic record, it was not a perfect match. “I was uncomfortable physically. They did sports. I was manager of the dingy team,” she now jokes. But if going to col- lege with a bunch of macho guys was hard for Robert, being married was even more challenging.

After getting his engineering degree, Robert was commis- sioned as an ensign in the U.S. Navy. Soon after that, he mar- ried a Maryland woman, with the newlyweds settling into a house in Washington, D.C. And so he would spend most of his adult life—building a stellar career while struggling to be a good husband and family man. By his own admission, he did better as a father than a husband. For nearly forty years, he was married: first, for thirteen years (1960 to ‘73); and then for 26 years (1973 to 2000). While his marriages produced four daugh- ters (two with his first wife, two with his second), both wound up in divorce.

Everyone at the time thought Robert and his wife had the perfect life. But always in the background was that little quali- fication. Eventually, the Navy sent him and his family to the Boston area, so that he could get his doctorate at MIT. But the same compulsions would invariably surface. One night, he took a pretty nightgown from his wife’s dresser, then accidentally fell asleep in their bed with the nightgown spread on top of him. His wife never said a word.

His second marriage, this time to an accountant, lasted twice as long, but did not bring an end to these fantasies. Then, one day, in the kitchen of their northern Virginia townhouse, while his wife was making pancakes: “I walked upstairs and Robyn bubbled up. I was calm and told her, ‘I want to be a cross- dresser, and I may want to take hormones.’ That was the end of our marriage.” While they stayed together for more than a year, his wife became more disengaged. Their sex wasn’t very good. And his wife’s frustration and sense of betrayal at times would erupt into rage. “She became very, very angry and would try to choke me or flash a butcher knife (in the direction of his geni- tals). ‘You don’t need this,’ she said. One time she had me down on the floor. She was afraid of what she would do to me. She thanked me for giving her a reason to leave the marriage.”

Robyn and Emery each thought that marriage would bring respectability and reassurance about their gender identity. “Nor- malcy”—that was the goal. But that pipe-dream proved naïve. “The happiest day of my life was when I had a hysterectomy in 1989,” Emery says grimly, looking back.

A Thoroughly Modern (Cyber) Romance

With marriages over, kids grown, and more than half their lives behind them, the two were ready to bid farewell to their bor- derline lives—no longer resisting, but rather embracing the per- sons they felt they were. Radical change began as a series of small, tentative steps. February 7, 1999, is etched in Carol’s mind as the date on which she resolved to change. “I was living someone else’s life—it just wasn’t mine. Overnight, my inner male woke up from jail, and I was there to stay.” That’s when Carol started searching the Internet for information on trans- sexuals and learned that Kate Bornstein, the transsexual writer and activist, was coming to the University of Michigan. Carol went to the talk, which led to going to “trans-inclusive” meet- ings at the university twice a month.

At 58, Robert was still a married man with a family living in Virginia. But major changes were imminent for him as well. He too started to use the Internet, and one day typed the word “cross-dresser” on his computer keyboard. This led to his join- ing a chat group. By 1997, his marriage was unraveling. De- pressed and at loose ends, he left for Seattle, hoping for a new start. Boxes of women’s clothes and a wig stayed hidden in the trunk of his car until he moved into the new house. Robyn came out of the drawer the following Easter—in church no less. A month later, she attended an intense, five-day trans- gender conference.

Robert, perhaps naïvely, still hoped to save his marriage and made a few trips back to the East Coast. But when he revealed to his wife he had been living full time as Robyn, it was obvi- ous the situation had become impossible. One day after return- ing to Washington State, he went to a shopping mall as Robyn. Getting her ears pierced, she told the saleswoman she had at last gotten her mother’s permission, at the age of 61.

By February1999, for both Robyn, now 62, and Emery, now 56, self-acceptance was at hand. And in this Digital Age, what better way for two shy, isolated souls to connect, one living in Seattle, the other in Ann Arbor, than on the Internet? Each had joined a support and networking e-mail list for over-fifty trans- gender people. In this safe haven, a fantasy game was drawn up, complete with fictional biographies. However, in this ver- sion, each child would be the correct gender—the gender they felt was the right one.

Robyn joined as a girl of sixteen; Emery joined as a rascally boy of twelve. Robyn came up with the idea of having a virtual Sadie Hawkins’ Day dance, in which the girls could pick out their partners. Playing a shy girl, Robyn asked a boy named Emery to be her date. He accepted, and by that night the two “teens” were going steady. It wasn’t long before the adult Emery and Robin were chatting on the phone, sharing e-mails, photos, and gifts.

A couple of months later, Robyn flew from Seattle to De- troit-Metro Airport to meet Emery in person. There he was at the gate, waiting for his lady with open arms and a bouquet of Toot- sie Pops. The next day, after talking through the night, Emery took Robyn for a walk in the park, sitting her down on a bench that had a straw angel on the back, and words, written with a black marker, that read: “Emery (Heart) Robyn.” Then, drop- ping to his knees, he asked for her hand in marriage.

Several months later, the two were married in Washington State. In order to avoid any potential legal hassles, on their mar- riage license Robyn was listed as male and her spouse-to-be as female—which on that day happened to be true. At their formal church ceremony, with about thirty friends on hand and with the strains of “Lady in Red” played in the background, Robyn entered the room wearing a floor-length burgundy gown made of satin; Emery opted for a more casual look, attired in a turtle- neck, dark slacks, and a sports coat.

By this time, Robyn had one more decision to make— whether or not to have Sex Reassignment Surgery (SRS)—a very personal decision. Some transsexuals are perfectly con- tent to live full time as a woman, without changing their gen- italia; some can’t afford it or simply don’t want to endure the lengthy process. Previously, Robyn had gone through most of the steps: psychotherapy, hormone replacement, a legal name change, and living full-time as a woman for at least a year— all of which were necessary before authorization could be given for SRS. In the end, Robyn opted for the complete pack- age. Three months after her wedding, on her 63rd birthday, she traveled to a Portland, Oregon, hospital and was operated on by Dr. Toby Meltzer, a well-known gender reassignment sur- gery specialist. When she woke up six hours later, Emery was there to greet her. The next morning she carefully lifted the sheet, eying the bandages. “Yes!”, she exclaimed, making a celebratory fist pump.

Emery got his chance about a year later, when Dr. Meltzer performed top, but not bottom surgery on him. “That’s all that’s legally required,” he says. “Have not had bottom because it’s not very good yet, too involved, and I didn’t like the looks of the various pictures of outcomes. If I were younger, I think I’d feel differently about it.”

Life Today: Comfort and Companionship

Married for thirteen years now, Robyn, 76, and 70-year-old Emery Walters have a nice life in Maui. “We have a wonder- fully satisfying relationship,” Robyn says, in her no-nonsense manner. “I cook and he does the laundry.” Their relationship, however, is not without its complications and adjustments. “I don’t like the bother of shaving, and I’m going bald,” Emery gripes. Relations with their grown children, all eight of them, vary. Robyn says she is “very close” to her second and third daughters, but not to the other two. Emery’s only really warm relationship is with his 34-year-old son Archie, who is gay.

In a couple of respects they seem more comfortable in their former gender roles. Emery, perhaps echoing his life as Carol, still knits and does the sewing; Robyn, perhaps reverting back to her life as Robert, handles the bills, finances, and driving. Even with the benefit of a sex change, gender roles don’t al- ways change accordingly. “It takes Robyn half an hour to vac- uum. It takes me five minutes,” Emery says, laughing, adding: “My wife, who of course grew up male, is still stronger than I am. When we travel, she’s the one lugging the heavy baggage, and I’m tottering along behind like Stan Laurel with the lamp- shade. It can be embarrassing.”

But overall, life is good. The two like to hike with friends, in addition to swimming, strolling on the beaches, or just keep- ing an eye out for humpback whales. They also spend a great deal of time on their computers—Emery working on his latest self-published novel and Robyn consulting for the Navy and working on her beloved ham radio, a childhood hobby she still adores. She also remains a staunch activist for over-fifty transgender people, until recently running an on-line support group for the transgendered called Elder TG. A member of the Trans- gender American Veterans Association, she has twice flown to Washington, D.C., to openly pay respects at memorials to fel- low troops who have silently served their nation.

Strolling along with their guest on La Perouse Bay, with its eerie-looking landscape covered with lava, the site of Maui’s most recent volcanic activity, the couple is asked if it was all worthwhile. “Absolutely worth it. I’m now living my truth,” Robyn says, later adding: “It’s not perfect, but it’s damn close.” And, for Emery? “Meeting Robyn,” he says, “was like God whopped our heads together and said, ‘Here you go. This is for you.’ I can’t explain it any better, nor do I need to.” All of which prompts a final question: doesn’t their story raise a more fundamental question about what it means to be “nor- mal”? “‘Normal’ is what you set your washing machine to,” Robyn replies.

Terry Ann Knopf, a lecturer in journalism at Boston University, has written for the Columbia Journalism Review, Boston Magazine, and The New York Times, among other publications.

Discussion2 Comments

Emery, I met you today on the beach near our rented condo for 6 nights. After a merry Christmas greeting between us, you stopped and shared bits and pieces of this story and a business card. This is a fascinating, beautiful and painful story. I live the normal washing machine quote. I can use that with my students. I know that they represent such a wide variety of struggles that are probably unrealized at their age, but if I can share that message maybe they can find comfort in who they truly are. Blessings to you both, Charlotte- mom on the beach in Kihei

Robyn, we were classmates from kindergarten through Madison High graduation. You have led a remarkable life and your work in Hawaii is amazing. I hope these recent fires have not harmed you or your family and that recovery for the island and everyone’s lives can come before too much time has passed. It looks so devastating but the spirit of the people there will prevail.

All the Best,

Jackie