A SAINT SEBASTIAN pincushion sits on my desk. More voodoo doll than icon, the figure suggests something of the quirky iconography of the saint, and the ways that Sebastian imagery blurs so easily into the iconoclastic or the camp. Across the room, there’s a small icon on my bookshelf, a collage by a local artist in which a sinewy nude Sebastian out of some art history book leans back, almost post-coital, in the middle of an old magazine ad for cameras—“Ne perdez pas votre temps!” (“Don’t waste your time!”). As Hunter College professor Richard Kaye (1996) has written, St. Sebastian is “a figure who winkingly seems to mock religious ecstasy as an erotic put-on.” His eyes are lifted up, as they always are, though my eyes are drawn to the arrow in his side, his pale skin, that thin drift of hair on his chest. As Willard Spiegelman (2011) wrote of the visual eroticism of Peter Paul Rubens’ St. Sebastian in The Wall Street Journal earlier this year: “Talk about a combination of the sacred and the profane.”

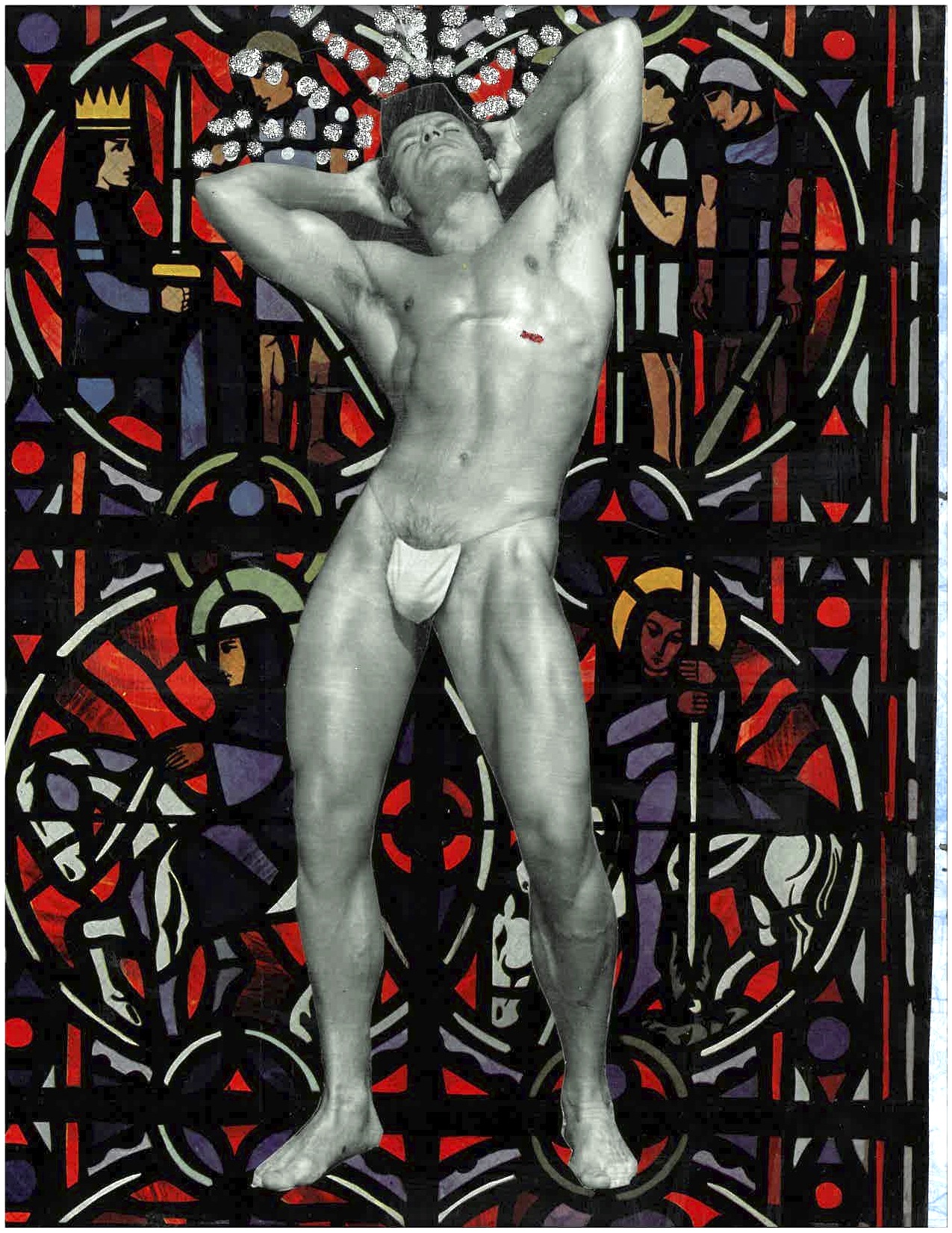

It was precisely this combination that impelled a small group of artists, most of us based in Columbia, South Carolina, to stage a collaborative art show centered on the image of Saint Sebastian, patron saint of soldiers and athletes, plague saint, gay icon. Conceived by visual artists Alejandro García-Lemos and Leslie Pierce, the show explored the iconography of the saint, who was martyred twice—the first one didn’t take, as Saint Irene pulled all the arrows out—his eyes always raised to heaven but his body writhing across the history of Western art in masochistic ecstasy. (The publicity art by Leslie Pierce, which juxtaposes a male pin-up with stained glass, captures, I think, some of the weirdness of this icon.)

Saint Sebastian: From Martyr to Gay Starlet was on display last fall at Friday Cottage Art Space, a gallery in one of Columbia’s historic downtown homes. Scheduled to open as part of a week of events leading up to the South Carolina Pride Festival in early September, the show featured the work of García-Lemos and Pierce, as well as work by media and performance artist Santiago Echeverry (from Tampa, Florida), filmmaker Betsy Newman, and a poet, to wit this writer. Other local artists contributed work as the project gained momentum.

Although there were campy elements to the show, we were deeply invested in what Richard Kaye (2004) has characterized as the saint’s “enduring and unruly power,” a favorite martyr of gay artists but easily adopted by any “who require a potent symbol of sexual disorder, political or personal rebellion or beatific self-surrender.” Kaye observes: “Sebastian’s classic Renaissance pose of youthful, beatific, pious surrender to a grisly, arrow-ridden fate, has proven to be of enduring fascination to writers and artists interested in non-normative forms of desire. For unlike other Christian martyrs, whose piety rendered them obsolete in an age of secularization, Sebastian suggested a different kind of martyr, one who had an inherent but ever-mutating perversity.” Elsewhere, Kaye (1999) finds in St. Sebastian “a visual metaphor for social outcasts and the politically suppressed.”

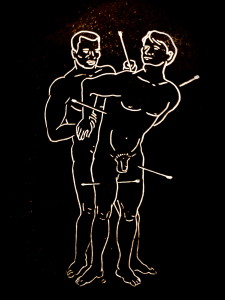

García-Lemos, a founder of Palmetto & LUNA, an organization promoting Latino arts and culture, began with a series of linocut prints, including a study for a larger painting titled “La Liberazione.” We used this print as a frontispiece for a limited-run hand-sewn poetry chapbook created for the show’s opening. (The cover was a beefy and bearded linocut Sebastian in a blizzard of arrows—some of these later Hello-Kitty-fied with gaudy hand coloring.) In the print, one naked man stands behind another, removing the arrows from his body and, apparently, fucking him at the same time, indicating that the removal of the arrows—of shame or name, stigma or social taboo—is connected to sexual pleasure. García-Lemos said he wanted to address taboos about representations of male sexuality. Other images were of penises or anuses pierced by arrows or a satyr with a phallus riddled with nails, suggesting prohibitions of sexual pleasure. (Many of these images are on the artist’s website at garcialemos.com.)

Pierce, who coordinates public programming and community relations at the Columbia Museum of Art (and whose Sebastian & Cameras sits on my bookshelf), worked with collages, situating traditional images of Sebastian in absurd contexts, such as a communist street demonstration in Paris, or displaying male nudes against religious backdrops. A local reviewer noted in Columbia’s alternative weekly Free Times (8/31/11) that “her collages depend as much on wit as on human anatomy.” She was also interested in Saint Irene, who nursed Sebastian back to health after he was shot, imagining her anachronistically and playfully as a kind of fag hag avant la lettre.

In my own work, I tried to respond to some of the images by Pierce and García-Lemos, but also immersed myself in the visual tradition. At the same time, because it was scheduled for gay pride week, I kept thinking about gay shame, and found myself reading everything from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and Michael Warner on gay shame to Gabriele D’Annunzio’s 1911 Le Martyre de Saint Sebastien. Publicity materials for the show included a saint’s prayer card, one of Pierce’s collages on one side, one of my “prayers” to Saint Sebastian on the other (“Arms be bound./ Arms be bound with rope and shame”).

While everyone had a different take on the tradition and the imagery, what I found most energizing was the collaboration, the ways our work fell into conversation. Both Echeverry and Newman took poems I’d written in response to images by García-Lemos and used those as the basis for short films. Newman, a documentary filmmaker and producer for educational television, worked with “Red Star,” a poem that was both a pæan to the pleasure of being sexually penetrated and a response to the García-Lemos print “Pierced Hole.” Using the poem as a soundtrack, she transformed it into a feverish meditation on penetration—mouths became flowers trembling with bees, arrows pierced skin (a free-range pork loin the stunt double for human flesh). For me the opening evoked Rocky Horror (is that my mouth?!), but that camp referent—appropriate as it was—was soon overwhelmed by the intense color of her close-ups of bright orange tithonia blossoms and the hum of bees.

A Colombian artist and professor of digital and media art at the University of Tampa, Echeverry took another poem, “Prick,” as his text, a poem about anti-gay discrimination written in response to another image, “Pierced Cock.” The film is a beautiful meditation on the male body, the camera exploring the body of a young man posed as Sebastian, while lines from the poem, like arrows in red, white, and blue, traverse the screen. (The short film “Prick,” the poem, and related images are available online at echeverry.tv/prick.)

At the opening on Sept. 1, visitors walked past a live Saint Sebastian in loincloth and pierced, his arms loosely bound and leaning against a tree. (Two local artists took turns as Sebastian.) Derek Jarman’s Sebastiane was projected, silent, on a wall above an outdoor bar. Inside, the central L-shaped gallery displayed the work of Pierce and García-Lemos, as well as sculptural pieces by Britt Hunt and Ivan Segura. The two films by Echeverry and Newman were screened in a small dark room off the gallery.

Another room was set up as a small chapel to Sebastian. With the help of my partner, Bert Easter, we transformed the room with prayer banners, church pews, and candles. In one corner was a skeleton pierced with arrows. A fireplace mantel became a campy altar to Sebastian, a small plaster saint surrounded by a mob of small action figures—Indians, knights, Green Arrow, a Smurf, all with arrows drawn and aimed, all of it framed by offertory candles. A large and abstract stained glass Sebastian by Amanda Segura filled the window opposite.

The prayer banners included bits of my own prayer poems in gold and red along with images of bound and pierced bodies. We found a large folk art crucifixion at a local auction, and I cut up the bodies of Jesus and the thieves—a torso pierced by an arrow on one banner, arms bound with rope woven in and out of the banner itself on another. There was something wicked and vaguely erotic about this little craft project, blasphemous even, appropriate to the themes that inspired the show.

In one corner we also had an interactive piece: a large soft mannequin. Thinking of both Celtic clootie tree and Latin American milagro traditions, we asked visitors to pin a prayer to the saint’s body. There were arrow milagro charms, pins, and long strips of blood-red paper. A nearby sign read, “Here in our chapel dedicated to Saint Sebastian, we ask that you pin your own prayer to the saint’s body—a prayer, a desire, a shame.”

The range of art—and the provocative nature of the work—was remarkable for South Carolina. After all, Columbia isn’t Austin or Atlanta. We’re outside the centers of queer culture. I was also impressed by the collaboration—in any arts community there’s a lot of talk about inter-arts collaboration, but I don’t think I’ve ever experienced the range and energy of collaboration that I found in this show. A local reporter called the show “the most ambitious art show” in the history of South Carolina pride events. All that said, I’m more interested in the cultural and political work this kind of show made possible.

The weather was beautiful. The DJ played a crazy mix. The Sebastian boys at the entrance made everyone pause and take photos with their phones. The galleries were full. People lit the offertory candles in the chapel. And by the end of the evening, the mannequin was covered in strips of paper, desires and shames written on the saint’s body, some silly, some predictable, some quite moving. “Accept or fuck off.” “My shame? I have no shame.” “Heal all of HIV.” “May all that are gay know themselves and be liberated by that knowledge.” “Marry GR and live happily ever after.” “That it’s not as bad as I think it is.” “My mom dies without pain.” “Not everyone knows.” And perhaps most moving of all, given the context: “Forgive my lack of understanding.”

References

Kaye, Richard A. “Losing His Religion: Saint Sebastian as Contemporary Gay Martyr,” in Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures. Routledge, 1996.

Kaye, Richard A. “‘Determined Raptures’: St. Sebastian and the Victorian Discourse of Decadence,” in Victorian Literature and Culture, 1999.

Kaye, Richard A. “St. Sebastian: The Uses of Decadence,” introduction to Saint Sebastian: A Splendid Readiness for Death. Gerald Matt and Wolfgang Fetz, eds. Kerber Verlag, 2004.

Spiegelman, Willard. “Finding Inspiration in the Flesh” [on Peter Paul Rubens, “St. Sebastian”], Wall Street Journal, 20 Aug 2011, C13.

Ed Madden is an associate professor of English at the University of South Carolina and author, most recently, of Prodigal: Variations, his second collection of poetry.