GRINDR, Manhunt, Gaydar, Scruff, Jack’d—for any gay man who’s been “out there” for any part of the last two decades, these websites or applications have become a familiar sight. For many men they occupy a substantial fraction of the day’s stream of experience, and for many others they form an integral part of their personal identity or sense of self.

But long before the arrival of the Internet, the social media, the hookup apps, there were GLBT people who lived, like everyone else, in what is now referred to as “real life.” I would argue that historically gay identity has always been characterized by a fundamental duality. The first identity is a response to the cultural prohibition or negation of homosexuality throughout history. This has been manifested as a lack of rights, a lack of visibility, a lack of social acceptance, a prohibition on the trappings of gay identity: sex acts prohibited, legal unions barred or blocked, blood donations refused, and so on, ad nauseam.

A second identity arose, partly in response to this repression, that stressed the value of overt visibility, of being not just quietly self-accepting but publicly out to one’s family and friends and anyone else who would listen. This is the ideal that would come to dominate cultural representations of GLBT identity for decades to come. In the late 1960s and ’70s, this concept manifested itself as protest marches, the Stonewall riots, the first pride parades, gender non-conformity in public venues, and various kiss-ins, love-ins, and so on.

Gay Liberation was all about bringing gayness into the light of day and dragging people out of the closet. But the closet never went away, and the result was a bifurcated system in which some people were “out” and others “in the closet”—wholly or in part, or perhaps in the process of “coming out.” This dynamic of “in” or “out” created a kind of existential dualism that still operates as a guiding principle of GLBT identity formation.

So, what precisely do the Internet and this age of cyber domination mean for these two polarized identities and the emerging middle-ground identity? If we were to think of an example of each type of identity outlined above, and a GLBT individual who epitomized each, we could come a little closer to imagining the cultural impact of the Internet.

Painting in broad strokes, an identity mired in a sense of prohibition could potentially be a description of a closeted gay man. The feeling of not wanting to inhabit or exhibit a gay sexual identity—and all the efforts of hiding that go with it—could be seen as a “negative space” identity. This identity would have certain hallmarks: refusal to accept a gay orientation openly, lying to close friends and family, internal struggles, deceptive practices to keep everyone in the dark, surreptitious encounters, and so forth. In the past, this may have emerged as seeking out sexual encounters in discreet and anonymous ways: outdoor cruising, for example, with its hidden and anonymous encounters. The defining feature of this negative space was the need to remain invisible: to indulge sexually but not identify as gay; to straddle two worlds without losing any crucial benefits in either of them.

In the modern era of technology, this negative space is clandestine both in the real world and now in the cyber world. The Internet allows even higher levels of anonymity than venues of the past. The classic strategy on Grindr, Scruff, et al. is to display a photo of one’s torso without a head and its all-revealing face. (A related strategy would be to display a fake face photo.) Such a user is also likely to offer very few clues that would give away his actual identity.

Considering the impact of the Internet on this negative identity, we need to keep in mind the nature of cyber reality, which is able to do two opposing things simultaneously. It offers the possibility of total anonymity on one extreme, or the potential for incredible visibility, even a kind of fame, on the other. Between these two extremes, the user’s relative anonymity or visibility can be fashioned as a (semi-)fictitious creation either way: it can act as a projection of a total falsehood or an altered version of the reality of an individual’s life. Prior to the great technological advances of the last few decades, there was no technological platform that could provide this chameleon-like ability to inhabit different identities at will. (Stage costumes were probably the closest equivalent.) You don’t like your profile picture? Use a more attractive one or Photoshop your features just a tad. Or, if you’d prefer, remain the ultimate mystery: a presence behind a screen with no visible characteristics—the alluring (and annoying) blank profile.

To move back to the “negative space” for GLBT identity, it is in the nature of the Internet to enable the closeted to operate in full stealth mode. The unprecedented success of a mobile geosocial networking application such as Grindr, created by Joel Simkhai in 2009, is testament to the fact that cyberspace has become the new haven for closeted gay men. The app was designed using geolocation technology to pinpoint other men using Grindr in one’s immediate vicinity, whose pictures and profiles appear in real time on your smartphone. This is the modern equivalent of cruising a park or restroom hoping to happen upon another like-minded individual seeking similar sexual release.

It’s interesting to note, but perhaps not surprising, that this app was pioneered by a gay man for use by gay men cruising. The straight equivalent came quite a bit later and was based upon the existing gay platforms. It’s also noteworthy that Grindr’s market was originally assumed to be closeted gay men, those who shied away from public venues like gay bars. But if it started as a “negative space” for a closeted gay identity, Grindr and its kind have gone on to become the defining feature of the gay community, the one thing that just about everyone has in common.

What this suggests is that there is also room for a “positive space” identity, which would be the individual who is out in real life and authentic in the cyber world. This individual publicly acknowledges a GLBT identity while also maintaining visibility in virtual spaces. This is usually represented by someone who publicly displays a clear face picture and is comfortable—possibly even militant—in doing so, often specifying in his profile that no one without a face pic need apply.

On that topic, a recent trend on dating and hookup apps is the ostracism of users who don’t include a face picture with their profile. And not just any face picture: it must be recent, well-lit, and free of sunglasses. (Many profiles use slogans like “If you’re faceless, I’m speechless” or “Be a man and show your face.”) Someone who doesn’t have a face pic on their profile (those infamous “torsos”) will probably be asked to provide one on first contact with another user. For this individual, the opposing forces of the two GLBT identities are at work. The need to hide and move in darkness behind a blank profile is countered by the demand for visibility, for revealing one’s authentic self. (And what is more inescapable than a photograph?) Ultimately, it’s a demand that the person “come out of the closet” in almost the old-fashioned sense.

THE SHEER RANGE of identity expressions that avail themselves to those who acknowledge their GLBT identity on some level and present themselves to the world is substantial and far-reaching. The first question is the Internet’s impact on the manifestations of these “positive space” identities. The paragon of positive identity would be the GLBT person who uses the Internet as a platform and a means of identity expression that is merely an extension of his real-life persona: the openly gay man who is out on-line and clearly displays his face for the world to see.

However, the world of virtual encounters is rarely that straightforward, and there are various means of identifying oneself that involve more layered identities. In the virtual world, participants have to swiftly alert other like-minded participants to their existence. Part of the lure of the Internet is its ability to reveal vital statistics quickly, with little left to the imagination, so as to screen out undesirable attributes and speed up the interaction. Thus a verbal shorthand has evolved to speed up the screening process. One example would be the widespread use of the phrase “straight acting/appearing” as a way to screen out those with camp sensibilities or effeminate mannerisms. While the use of these screeners can be traced back to gay personal ads in the 1970s, the cyber world makes ample use of them. Some apps have identified “tribes” that men can subcribe to—such as “Bear,” “Geek,” “Jock,” “Poz,” and so on—affiliations that become part of your identity whenever you inhabit this world. While this self-sorting method does have its efficiencies, it might also be seen as divisive, a source of exclusion and cliquishness.

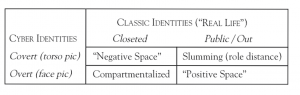

With the “pure” positions of “positive space” and “negative space”—the guy who’s out in real life and presents his authentic self in cyber world, versus the guy who’s closeted IRL (in real life) and conceals his identity, or presents a false identity, on the app—it’s time to consider the mixed positions. To understand these different groups and their cyber avatars, we need to be able to imagine four distinct positions or ways of identifying. In addition to the two consistent positions, there are two others that present a dissonance between everyday reality and virtual reality.

The first is the gay guy who is closeted or semi-closeted in real life spaces yet is quite open in the cyber world. Whereas the “negative space” identifier refused to display an accurate face picture, this person does not mind being out in virtual space. There may be high levels of deception—such as not giving away too many personal or real life details, the use of a false name, only choosing to meet at specific venues or under certain conditions—but by all appearances this guy is a star, everything you could want in a casual hookup. For such a participant, the app is a fantasy playground that’s a world apart from everyday life, and it should remain so. This individual may be heard saying, “I may be gay but it doesn’t define who I am” or “My private life has nothing to do with my work life.” There may even be a certain level of self-deception that leads this individual to believe that the virtual world and real world are further apart than they actually are, which may result in vastly different behavior in the two compartmentalized domains.

The second position is that of the gay person who’s out and proud in real life, and may even be actively involved in GLBT social and political arenas, but who doesn’t necessarily want it to be widely known that he’s active on Grindr or Scruff. When it comes to the cyber world, a certain degree of surreptitiousness comes into play. This behavior is motivated by a desire to remain anonymous in the world of virtual encounters: a certain distancing of roles occurs that is typified by secrecy on-line (a reluctance to show a face picture), versus a high degree of visibility in the real world. For this person, there may be shame in reconciling the differing aspects of his personal identity—the prominent and successful person for whom cruising on the dating apps is a kind of “slumming.” Such a person might have a desire to go incognito when on-line and engage in less wholesome activities there.

The two “mixed” identities demonstrate that, beyond pure visibility or pure anonymity, the social network allows for various permutations on visibility and on personal identity itself. How a person chooses to identify himself in this world has much to do with what he wants from it, whether a simple hookup, the faster the better, or the opportunity to play the game of hooking up, or to be on display, or just to make friends, as many users claim. Are Grindr et al. ultimately a furtive world, the Ramble in cyberspace, or is it the ultimate Panopticon, where everyone has a perfect view of everyone else? People can try to separate the two worlds, but ultimately they leak into one another, as when you spot your neighbor on Grindr or your coworker on Scruff. And, of course, hookups do take place on occasion, perhaps quite frequently, which is the whole point, after all—and the point at which “real life” gets the upper hand, and the reliability of profile pics and specs is put to the test.

At the risk of schematization, the two realms of identity formation can be crossed with the two ways of being (out versus closeted) to produce a typology with the four positions that I’ve described:

The four ideal types that I’ve suggested are formed by the intersection of real life spaces and the cyber world. The Internet allows GLBT individuals to put their identities into motion in varied and volitional ways: it provides a range of choices for how you will be identified and what version of yourself you will choose to put forward in the virtual world. The significant interplay between the Internet and GLBT culture has occurred due to precisely the duality inherent in both: secrecy versus openness, anonymity versus identity. Given the whole history of the closet and the concealment of one’s true nature, the dualities of social media encapsulate those of the GLBT community in a special and particular way. The importance of social media to modern gay identity is evident every time you sign in to your favorite mobile dating application: for better or worse, this is where much of the cultivation of personal identity takes place in the digital age.

Krishen Samuel is a writer and speech pathologist based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He can be reached at krish-s@hotmail.com.