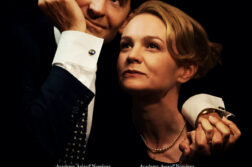

The Kids Are All Right

Directed by Lisa Cholodenko

Mandalay Vision

THE KIDS Are All Right deals in matters of sexual ambiguity and raises some bold questions about desire and identity—questions that the movie then ignores for the most part. Let me say that I enjoyed watching these fine actors in this artfully written script. It will succeed for many in presenting a normalized portrait of two women in love who are raising a family. Nic (Annette Bening) and Jules (Julianne Moore) have grown a little bored with their long marriage just as “the kids,” now teenagers impatient for liberation day, decide they want to know their biological father.

You can see from the start that it won’t take much to pull a thread and start things unraveling, so when Mark Ruffalo rides in on a motorcycle, well, what can we expect? He is Paul, the sperm donor and long-lost genitor of the family: so a seed of curiosity has been planted that will carry the narrative to its end. More than that, Ruffalo’s presence serves to seduce the audience by summoning an image of the scruffy little hipster in a room with a beaker all those years ago. Now of course it’s true that sperm donors are a plain reality for many lesbian families. But the role is slyly sexualized here, and while I have nothing against cheap thrills, this is, to say the least, a notable move for what might be a breakthrough moment in lesbian representation.

Like Brokeback Mountain five years ago, Kids grants opposite-sex coupling more open representation than same-sex coupling. Jules is ravenous for Paul and screws him like her life depended on it. By contrast, in the scene with her uptight wife Nic, who tries to manufacture some heat by watching—wait for it—vintage 70’s gay male porn, Jules is hidden away under the comforter. To be fair, having Moore go down on Bening at all was kind of daring for this mainstream movie. But even sympathetic viewers might get the message that sex between two women doesn’t really deliver. What we’re supposed to be witnessing is the waning of desire in a long-term relationship versus the blaze of lust with someone new and different. But the gender of the participants has changed! And what about that gay male porn? The film behaves as if we aren’t supposed to notice these extravagant details.

Jules reassures everyone she’s gay (mostly by screaming “I’m gay” into a cell phone), that it was all a huge mistake, and that she wants her groovy middle-class California family life back. By this turn of events, the movie takes a nasty swipe at Paul. The enemy of family values, he ends up alone and unhappy for his life of emotional and sexual promiscuity. Shut out of the glowing domestic interior and disgusted with himself, he throws his helmet at the curb.

Kids wants to dramatize the difficulty inherent in long-term coupledom and make the point that when you get right down to it, the gender of the partners is incidental. Left dangling are more dangerous questions like the one Jules puts to Nic in a restaurant bar as the drama reaches its little crisis: “Are you even attracted to me any more?” The film retreats instead into a warm blanket of nuclear family unity, whose worth is simply asserted as beyond question. Which brings us to the film’s title: how are we to interpret it? “The kids are all right, even though they’re being raised by lesbians.” Not a ringing endorsement of gay parenting, but perhaps that reading is unfair. Although the script never references the title directly, the idiom of conventional wisdom rings through loud and clear. “Are the kids all right?” “Make sure the kids are all right.” And above all: “As long as the kids are all right … nothing else really matters.” This reading is of interest in light of some recent queer theory talk about the mystification of children as a sort of supreme force in our society, keeping us all in line. Sentimental enshrinement of children is a mainstay of traditional heterosexual family ideology, and there’s a way in which Kids sells a story about lesbians by playing to this fundamentally conservative impulse and placing its main erotic investment firmly in the hands (or hand) of a randy young man.

This is, I suppose, the perfect GLBT film for our times, what with gay marriage looming as the ultimate triumph of assimilation. Judging from this movie, it looks like gay people have at last been completely domesticated. There’s something both touching and annoying about the way this film wants to save Paul from himself, to stop him from wasting his manhood on stray transactions—be they in a closed little room, or with a menacing black Siren who works in his restaurant. Intelligent and sometimes poignant, The Kids Are All Right has enjoyed wide release and even garnered some Oscar buzz. It will probably ease acceptance in the land for certain gay families. But we still can’t help wondering what it means when, in this remarkable new lesbian picture, a cute straight guy with a motorcycle is the queerest character on the lot.

Gary Cestaro teaches in the LGBTQ Studies Program and the Department of Modern Languages at DePaul University in Chicago.