IF PIERRE S. DU PONT II (1870–1954) loved anyone in his long life, it was Lewes Andrew Mason, the young man who worked at Longwood Gardens as his driver and handyman. Doubtless Pierre felt affection for his wife, Alice Belin du Pont (1872–1944), but a working man from Delaware won his heart.

Unfortunately, family and friends have sought to erase Lewes’ presence from Pierre’s life, and this effort raises issues of prejudice and misunderstanding while it also denies the reality of a relationship that meant a great deal to one of America’s most capable and accomplished businessmen. Thus it is appropriate to rediscover Lewes Mason, to recall his life with Pierre, to make sense of Pierre’s generosity to Lewes both in life and in death, and to view the portraits of Lewes that history has left us, portraits that help explain Pierre’s deep admiration for an ordinary young man.

Lewes Mason was born in Delaware in 1896, and his first name reveals the city of his birth. (Alice usually misspelled it as “Lewis.”) He was first employed at Longwood in 1913, at the age of seventeen, along with his older brother Charlie. Lewes worked mostly as a handyman at Longwood, doing everything from gardening to house chores. When Charlie joined the U.S. Army in 1917 to go to war, Lewes took over his duties as Pierre’s chauffeur. He wore a suit and tie when he drove Pierre to work in Wilmington and to various events in Philadelphia, but he never wore a driver’s uniform, perhaps because Pierre often included Lewes in his social life.

From 1917 to 1918, Lewes became increasingly close to Pierre. He dined with Pierre and Alice at the DuPont-owned Bellevue-Stratford hotel in Philadelphia and even sat in their box for opera performances in Philadelphia and New York. In the summer of 1918, Lewes became engaged to Catherine Chalfont, whose last name indicates her family’s origins in Pennsylvania. Pierre gave Catherine a silver tea service as an engagement gift. He even hired architects to design a house for Lewes and Catherine to be built on Longwood’s grounds. Marriage would not end Lewes’ ties to Longwood and Pierre.

Sadly, Lewes was felled by the Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918 and died at Pierre’s Longwood home on October 19 of that year. Alice records in her ever-cryptic diary: “Lewis died at 7.30. Pierre all in.” In the months before Lewes’ death, Pierre had purchased over 300 shares of stock for his young employee in several blue-chip companies, including DuPont. The income from the portfolio was slightly over $100 a month, which would have doubled Lewes’ income from his job. After the young man’s death, Pierre asked Lewes’ mother, Virginia (Jennie), if he could administer Lewes’ estate, and she agreed. Pierre subsequently sent Virginia a monthly check for $100, for which she was most grateful. (In 1919, the portfolio was valued at almost $45,000, or over $550,000 in today’s dollars.)

Pierre also arranged for Lewes’ burial and purchased two lots at Union Hill Cemetery in Kennett Square, Pennsylvania, arranging as well for the perpetual upkeep of the grave. (Jennie and Charlie are interred next to Lewes.) But by far the most expensive effort on behalf of the deceased was Pierre’s offer to build a new wing for the Chester County Hospital (CCH) in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Pierre had long been associated with this hospital, to which he occasionally gave a donation. He became fonder of the institution after Lewes was treated there for a serious hip injury that occurred in 1917 when the young man fell from a tree at Longwood. Pierre and Alice laid the cornerstone for the new building in 1924, and the wing was opened in 1925. Additional contributions came later to cover the cost of medical equipment and housing for nurses.

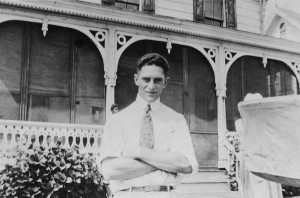

Pierre also engaged three artists to paint portraits of Lewes based on photographs he obtained from Jennie. Recreating Lewes’ image became a primary concern for Pierre, since he had no photographs of his own, and there are none showing the two men together. Pierre requested two portraits from Clawson S. Hammitt (1857–1927), an accomplished portraitist: one of Lewes and one of Pierre. He also engaged (at Alice’s suggestion) Eleanor F. Crownfield (1867–1950) to paint a portrait of Lewes based on a photograph depicting the young man in front of a white frame house, in a white shirt and tie, his bare arms folded in front of him, his face a smiling testament to youth and happiness. Another portrait was requested from Fred W. Wright (1880–1968), who also painted a portrait of Pierre’s brother Irénée in 1931, the same year he painted Lewes’ portrait. Wright’s portrait of Lewes now hangs in the Chester County Hospital. When the building was dedicated in 1925, Pierre was delighted to see that the Board of the CCH had commissioned a portrait of Pierre, which also hangs in the Director’s office almost directly across from Lewes’ portrait. (Neither painting is in public view, although a wall display in the Mason Wing gives a good account of the Mason-du Pont connection.)

The history of the paintings underscores some of the difficulties the du Pont family had with the relationship between Pierre and Lewes. Biographical accounts of Pierre’s life also show the discomfort the family felt over Pierre’s extravagance in memorializing a youth who died at the age of 22, and whom Pierre had known for only five years.

In his 1961 book, The Du Ponts: From Gunpowder to Nylon, Max Dorian writes: “An oil painting of Mason occupies, as it always has, the place of honor over the fireplace in Pierre’s office at Longwood.” This was Hammitt’s painting, which was removed from its “place of honor” at least thirty years ago. While no one at Longwood can recall exactly when it came down, the painting has been in storage for decades. The portrait depicts Mason from the chest up in a dark suit wearing a tie with a green stick-pin. He appears much older than 22. Above his broad forehead, Lewes’ hair is dark and wavy. His expression is somber, and the whole atmosphere of the portrait is rather dark, even funereal. In contrast, the Wright portrait based on the same photograph is much brighter.

Pierre had hoped that the Crownfield portrait would reveal Lewes as he wanted to remember him, with a smile and a cheerful countenance, and dressed more casually. Crownfield changed the setting for the portrait, placing Lewes in a grove of trees at Longwood. While she captures his face extremely well, the perspective is disjointed. Pierre was never happy with the final product, and, although he paid Crownfield $1,300 for her efforts (she reworked the portrait several times, never getting it right), Pierre did not display the painting, which was completed in 1925 and intended for the new Mason Wing. Unfortunately, Crownfield’s painting has suffered major damage in storage at Longwood Gardens.

In written accounts, Pierre’s relationship with Lewes tends to be neglected or described inaccurately. A few biographers of the du Ponts have mentioned Lewes Mason and Pierre’s affection for him, though the standard biography of Pierre, Pierre S. du Pont and the Making of the Modern Corporation (1971), by Alfred D[u Pont]Chandler and Stephen Salsbury, does not include any reference to Lewes. The most detailed account of Lewes and Pierre appears in Leonard Mosley’s 1980 book, Blood Relations: The Rise and Fall of the du Ponts of Delaware. Mosley’s title suggests a certain animus toward the family, and the book includes details that would certainly not endear him to the du Ponts.

Mosley begins his history by describing Pierre’s inability to attend a company board meeting the day before Mason’s death, writing that Irénée “was embarrassed by the real reason” that kept Pierre at Longwood. Pierre’s brother lunched at Longwood on October 16; thus he knew of the young man’s grave illness, but how Mosley knew Irénée was “embarrassed” is unclear. Still, Irénée did not tell the DuPont Board that his brother was tending to his sick driver, and so embarrassment may be inferred. Mosley goes on to say that “the intimacy Alice wanted was reserved by P.S. for the young man who was his chauffeur, valet, and handyman.” Mosley adds, however, that there is no evidence that Pierre and Lewes ever engaged in any sexual activity.

Pierre, in keeping with his reserved nature, wrote little about Lewes after the young man’s death. He did mention in a letter to a physician that Lewes “was a fine man and I feel his loss keenly.” He addressed Mason as “Lew” and described him succinctly in another letter as “my boy Mason.” Pierre’s affection for Lewes is appropriately characterized in the few studies that mention Lewes as “paternal,” and much of Pierre’s generosity toward Lewes strikes one as just that—fatherly. Pierre and Alice were in their forties when they married in 1915, with little hope of children before them—particularly if Pierre was not interested in consummating the marriage.

Lewes Mason was, in effect, Pierre’s surrogate son, even though Pierre’s largesse and attention suggest the love was more than filial. Lewes’ importance to Pierre is underscored by a remark Alice made in her diary a few days after the young man died: “Hard realization of my place.” Mosley interprets this remark to mean that Alice was unable to give comfort to Pierre, or to compensate for the lost Lewes. Alice’s diary entries before Lewes’ death show her awareness of being isolated from the relationship between her husband and his driver. She observed them listening to music from a Victrola, sitting side by side behind Pierre’s desk in close consultation, and engaging in conversations that excluded her. (Alice was almost completely deaf but could read lips, unless faces were turned away.)

While the nature of the relationship between Lewes and Pierre has been the subject of gossip for years, a 1996 A&E film biography about the du Ponts did raise the question of Pierre’s sexual orientation. One of the film’s contributors, Gerard Colby, says that “some in the family believed he [Pierre] was gay.” Most of the people who appear in the film are friendly to the family. Thus the producers added some controversy when Colby was included, especially since his 1974 book, Du Pont: Behind the Nylon Curtain, caused the family to rally against Colby and his publisher, Prentice–Hall. Mosley brings up the gay issue near the end of his prologue, as he describes the need for Pierre to rein in his emotions: “It would be dangerous to let them [Pierre’s cousins] know how badly he had been wounded by Lewes Mason’s death. The more unscrupulous among them could easily make a great scandal out of it.”

Mosley is probably referring to A. I. du Pont (1864–1935), who was ousted from the company by Pierre in 1916 at least in part because Alfred divorced his wife Bessie Gardner du Pont (1864–1949) after having had a well-known affair with his cousin Mary (Alicia) Bradford (1875–1920), whom A. I. later married. The lawsuit that forced A. I. out of the company was long and acrimonious, so he was probably in a vengeful mood toward his cousin Pierre. However, he never used the Mason relationship as a weapon against him.

Yet if one believes that Pierre was indeed homosexual, then one needs to consider how difficult a hand he was dealt. (The New York Times review of Mosley’s book refers to Pierre as a “repressed homosexual.”) Lewes, despite his obvious affection for the older man, could never have requited Pierre’s love. Nor could a man of Pierre’s stature and fame have simply run off somewhere for secret assignations. Even if he could have kept Lewes close after the latter’s marriage, he would still have had to share Lewes with Catherine. In any event, death changed everything, and all Pierre was left were intense moments of grief and many tearful visits to Lewes’ grave.

In a 2009 biography published by Longwood Gardens, Pierre S. du Pont: A Rare Genius, the accompanying DVD makes no mention of Lewes, but the written text includes some pages about Pierre’s philanthropic generosity, noting that Lewes’ death heralded Pierre’s career as a major donor to many different causes, particularly public schools in Delaware, the University of Delaware, and, of course, the Chester County Hospital. The book also includes the two photographs on which the portraits of Lewes were based.

At least this recent study does not shy away from the Mason story, as so many others have. Still, a photo exhibit in the Longwood house shows the 1924 cornerstone event at the hospital, without a word about Lewes. Moreover, talk of returning the portrait of Lewes to its place in Pierre’s study has been only talk; the painting remains in storage. Surely the time has come to give Lewes Mason some recognition and remembrance, and to honor the love that Pierre S. du Pont felt for this young man. Pierre du Pont gave America and the world the extraordinary legacy of Longwood Gardens. Surely there is room for his most profound relationship to be remembered and cherished as well.

John Allen Quintus was instrumental in creating the German-American Dialogue Center in Magdeburg and founded the Vienna Initiative for Central Asia. Since retiring from the State Department in 2005, he has taught at the University of Delaware.

Discussion1 Comment

Pingback: Longwood Gardens in October, Part I | gardeninacity