The following is excerpted from The Real Tadzio: Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice and the Boy Who Inspired It (Carroll & Graf, 2003).

ON A DECEMBER afternoon in 1910 Thomas Mann treated his immediate family circle, his wife and elder brother, to a reading of a short work of fiction, “The Fight Between Jappe and Do Escobar,” which he had just that day completed. Mann, who was then in his mid-thirties, had been feeling as ill-humored, as cantankerous, as irritably out of sorts, as one of his own neurotic protagonists. He had laid aside (temporarily, he assumed) a projected comic novel to which, as it transpired, he would return only at the very end of his life and which was first published, in English, with the rather unwieldy title Confessions of Felix Krull, Confidence Man: the Early Years, in 1955. He had also been troubled, although less profoundly than might have been predicted, by the horrific death of his younger sister Carla. The garish circumstances of her suicide—she had swallowed, as Mann himself was later to write, with an unnerving absence of sibling warmth, “enough potassium cyanide to kill a company of soldiers”—suggested that poor Carla had ceased to make too much of a distinction between her own life and the melodramas in which, as a hopelessly third-rate actress, she had tended to be cast.

Unable to channel his intellectual energies into any form of extended labor, Mann had quickly dashed off his new story after an unexpected encounter with a childhood friend, Count Vitzum von Eckstädt, revived memories of their schooldays together, memories which, as was almost invariably his custom, he sought at once to transmute into fiction.

“The Fight Between Jappe and Do Escobar” is a minor but perfectly achieved example of Mann’s storytelling genius. It centers on an abortive fist-fight between two youths, a German and a Spaniard, refereed by a somewhat equivocal dancing-master, Herr Knaak (“who picked up the edge of his frock-coat with his finger-tips, curtsied, cut capers, leaped suddenly into the air, where he twirled his toes before he came down again”), and observed by a third boy, a twelve-year-old English cherub named Johnny Bishop. This is how Mann pictures Johnny in his Sunday finery: “He was far and away the best-dressed boy in town, distinctly aristocratic and elegant in his real English sailor suit with the linen collar, sailor’s knot, laces, a silver whistle in his pocket and an anchor on the sleeves that narrowed round his wrists.” And here is Johnny on the beach, languorous and naked: “He looked rather like a thin little cupid as he lay there, with his pretty, soft blond curls and his arms up over the narrow English head that rested on the sand.” In light of what was to happen to its author a mere six months later, such a description of pubescent androgyny now seems eerily prescient.

In May of the following year, fretting over head-, stomach-, and tooth-aches (he was a lifelong martyr to his teeth), still incapable of settling down to real work, Mann decided that what he needed was a long holiday in the sun. So, accompanied by wife Katia, who was also ailing, and brother Heinrich—a by no means negligible novelist in his own right, even if his reputation had already been overshadowed by Thomas’s precocious neo-Goethean aura (if ever a writer wore his learning lightly, it wasn’t Thomas Mann: Brecht, his arch-enemy, would mischievously refer to him as the “Starched Collar”)—he left Germany to spend a few weeks on the island of Brioni, off the Dalmatian coast.

From the start this hoped-for sabbatical from the agonies of creation was plagued with distractions and dissatisfactions. The weather was cold and cheerless, none of the trio cared much for Brioni, and Thomas was especially incensed to discover that an unbroken line of chalk cliffs rendered a pedestrian’s access to the Mediterranean, for which he had a Northerner’s thirst, virtually impossible. Worst of all was the hotel, albeit the island’s finest. The Archduchess of Austria was among the company, and protocol required even non-Austrians to rise to their feet as she entered the dining room, which she affected to do only after all the other guests were seated. It was an irksome and demeaning performance made the more exasperating by having to be gone through a second time once the meal was over.

On impulse the Manns elected to cut short their sojourn and travel onward to what was then, as it is today, by far the least disappointing tourist spot in Europe: gorgeous, gangrenous Venice, “the incomparable, the fabulous, the like-nothing-else-on-earth,” in Thomas’s ecstatic phrase. At Pola they bought passage on a steamer, aboard which they were both amused and bemused to witness the antics of an elderly, goatish queen (in the homosexual sense of the word) who had contrived to ingratiate himself with a party of boisterous clerks out on an excursion. With his crudely dyed moustache and grotesquely rouged cheeks, he reminded them all of Herr Knaak (who also, intriguingly, pops up in one of the most perfect of Mann’s short stories, Tonio Kröger). A more disquieting incident followed at the steamer’s landing stage. The Manns had duly transferred their luggage to a gondola which would take them to the Lido, at whose Grand Hôtel des Bains they had two adjoining rooms reserved. But their gondolier proved to be a surly, incommunicative fellow who, although he steered them skillfully enough, proved reluctant to stay around to collect his fare when they disembarked. It turned out that, having had his license revoked, he had been alarmed by the presence on the pier of a cluster of harbor policemen.

Eventually, however, the three were installed in the sumptuous Hôtel des Bains. And it was there, on their first evening, as they lounged among the elegant, cosmopolitan crowd waiting for the gong to be rung for dinner, that Thomas’s attention was drawn to a nearby Polish family, which consisted, in the momentary absence of the mother (who, like the Archduchess of Austria, appears to have been an adept of the delayed entrance), of three starchily outfitted daughters and one very young son. Amazingly, this sailor-suited ephebe—of, to his connoisseur’s eye, near-supernatural physical beauty and grace—was the very image, teased into life, of the Johnny Bishop whom Mann had conjured up just six months before.

Panicked by a cholera alarm, uncannily portrayed in the pages of the novella-to-be, the writer, his wife, and brother hastily quit the Lido only a week after their arrival and renounced all notion of a holiday. Back home—or, rather, in his newly built summer villa in Bad Tölz in Upper Bavaria—Thomas at once began work on Death in Venice, taking one entire year, the twelve months between July 1911 and July 1912, to compose the seventy-odd pages of his novella about an aging writer in febrile thrall to the ultimately fatal charm of a Polish adolescent. It was first published, to well-nigh universal acclaim, in two successive 1912 numbers of the Neue Rundschau review and thereafter in book form, with an initial print run of 8,000 copies, in February 1913. That edition sold out at once, and the novella has been ever since, in one edition or another, in one translation or another, an international bestseller, still the most popular and widely read of all Mann’s fictions. In fact, almost before it appeared, its fortunate publisher, Samuel Fischer, had proclaimed, with pardonable hyperbole, its instantaneous “enrollment into the history of humanity.”

In the years that followed the 1911 trip, when Death in Venice would, as Fischer had foreseen, come to be recognized as one of the undisputed classics of contemporary European literature, Mann was not averse to acknowledging a debt to the sublime happenstance that had laid out before him, in the correct order, a sequence of narrative units that could scarcely have failed, even in lesser hands than his, to engender a masterpiece. Even now, nearly a century after the event, it is not generally realized, save by the many specialists of Mann’s work and life, that virtually everything experienced by Gustav von Aschenbach in the novella, short of his premature death on the beach, had first happened to the author. Yet Mann never sought to camouflage just how little of a novelist’s imaginative gifts had gone into this particular tale. More than once he admitted to the world that there really had been an effeminate, posturing fop, a gruff gondolier, an aristocratic Polish family, and, of course, a beautiful boy, as he himself wrote:

Nothing is invented in Death in Venice. The “Pilgrim” at the North Cemetery [who makes a brief cameo appearance in the prelude to the story proper], the dreary Pola boat, the gray-haired rake, the sinister gondolier, Tadzio and his family, the journey interrupted by a mistake about the luggage, the cholera, the upright clerk at the travel bureau, the rascally ballad singer, all that and anything else you like, they were all there. I had only to arrange them when they showed at once and in the oddest way their capacity as elements of composition.

Or, again, of his fateful sojourn in Venice:

A series of curious circumstances and impressions combined with my subconscious search for something new to give birth to a productive idea, which then developed into the story Death in Venice. The tale as at first conceived was as modest as all the rest of my undertakings; I thought of it as an interlude to my work on the Krull novel.

Yet, surprisingly, in that selfsame year of 1912, Mann was complaining to Fischer of the novella’s “errors and weaknesses” and describing it to his brother Heinrich as “full of half-baked ideas and falsehoods.” (By one of several weird coincidences that are threaded through our story, Heinrich had made his own international reputation with a lurid account of another intellectual prostrated by an unworthy object of desire, the novel Professor Unrat, the tale of a sadistic schoolmaster who falls flat-on-his-face in love with a blowsily alluring nightclub chanteuse. If no longer very much read, it is recalled still as the basis for the 1930 film, Josef Von Sternberg’s Der Blaue Engel, or The Blue Angel, which first dangled Marlene Dietrich before a mesmerized world.) Had he been afforded the opportunity of writing Death in Venice over again, Thomas insisted, he would have made it significantly less of a “mystification.” And, indeed, as we have long known, the reality is that, notwithstanding his claims to the contrary—that the novella’s narrative had simply and magically unfolded before his eyes and that all he had had to do was transcribe it from life, as though taking dictation from God—he had been as economical with the factual truth as the majority of his fellow novelists.

Since fiction and autobiography are distinct if frequently overlapping categories, there were of course, as ever, a number of trivial divergences in Death in Venice from what we now know to have happened on the trip which inspired it. Aschenbach, for example, is alone in Venice, Mann was accompanied by his brother and wife (and, as is clear from her memoirs, the complaisant Katia was well aware in what direction her husband’s eyes would usually rove, not excluding, in the later years of their married life, towards his own strikingly good-looking son Klaus); Aschenbach has an estranged daughter, Mann was not yet a father; Aschenbach brazenly pursues Tadzio just about everywhere the boy goes, Mann (according, again, to Katia) attempted to restrain himself, to rein in his passion; and so on.

Even in his supposedly humble and self-deprecating statement of the “curious circumstances and impressions” that led to the creation of Death in Venice, Mann could not resist dissembling, refashioning his material to make it appear more miraculous than it was in reality. The “mistake about the luggage,” for example, listed above among the elements transferred—verbatim, as it were—from life into fiction, involved only Heinrich’s cases, not Thomas’s or Katia’s; the rumor of cholera emanated not from Venice itself but from as far away from the northeastern coast of Italy as Palermo; and, more crucially, even before writing Death in Venice, Mann had long mulled over the idea of a short story whose subject would be the catastrophic loss of dignity suffered by a great and mature artist infatuated by a very much younger object of his lust. Nor had he been considering just any great and mature artist. His protagonist was to have been Goethe himself, who in his seventh decade fell in love with (and even, unbelievably, proposed marriage to) the seventeen-year-old Ulrike von Levetzow. Mann, although something of a prude in his public self-presentation, was patently fascinated by the expression “to fall in love,” by the notion that love is something into which one falls.

Of greater significance, though, were the liberties that he allowed himself to take with the character of Tadzio. In the first place, the boy’s name was not Tadzio at all—or Thaddeus, for which “Tadzio” is the diminutive—but Wladyslaw. This, at least, was probably not a deliberate subterfuge on Mann’s part (when he set to work on the novella he sought advice on spelling from a Polish-speaking acquaintance). What Aschenbach, his protagonist, hears on the Lido when the other children start calling the Polish youth to play is “something like Adgio—or, often still, Adjiu, with a long-drawn-out u at the end.” And that is exactly what Mann himself would have heard, save that Adgio—or, correctly, Adzio—is, via “Wladzio,” short for “Wladyslaw.”

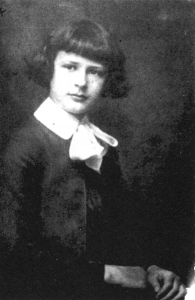

Even more significantly, Adzio was not a youth but a child. Wladyslaw Moes—the real boy’s real name—was born in the second half of 1900, which means that, at the time of their encounter on the Lido, he whom Mann would complacently portray as “a longhaired boy of about fourteen” was not quite eleven years old, a significant difference where approaching or receding puberty is concerned. Furthermore, although his older beach companion “Jaschiu” (Mann’s phonetic spelling of “Jasio,” the vocative form of the name “Jas”) also existed, and was called Jan Fudakowski, he was in reality Adzio’s junior by a few months and therefore neither the “sturdy lad with brilliantined black hair” of the novella nor, a fortiori, the muscular hunk, visibly in his late teens or even early twenties, of the film that Luchino Visconti adapted from the book in 1971.

In fairness to Mann, it should be pointed out that, if he aged Tadzio by three years—if, to borrow the term used in the antique trade to define the deliberate, frequently fraudulent “antiquation” of furniture, he “distressed” him—then he took a far greater liberty with his own fictional surrogate. In 1911 Mann was thirty-six years old. As for the hero of Death in Venice, it is in the novella’s second sentence that the reader learns that the once von-less Gustav Aschenbach had officially earned the right to be addressed by the nobler moniker “Gustav von Aschenbach” only, as the text has it, “since his fiftieth birthday.” Aschenbach is, then, older than fifty. He may well be, in fact, approaching sixty, and therefore by some twenty years Mann’s senior.

How should we interpret the fact that Mann chose to alter the factual age, so to speak, of not one but both of these fictional characters? As part of a structural tactic whereby—it being absolutely crucial to the novella’s meaning that Aschenbach be shown to be an artist at the very height of his literary renown—it became necessary, if the “miraculous” parallels with the real incident were to be upheld, to add a few extra years to Tadzio’s own age? Or, less generously, as a sneaky endeavor by Mann to underplay, even minimize, the not always latent eroticism of his story, in that the desire for a prepubescent boy on the part of a late-middle-aged man would stand a chance (back in 1911 if not necessarily today) of being regarded as less threateningly carnal than that of one in his thirties? Or simply as a ruefully ironic reflection of how old Mann actually felt when caught in the headlamps of the eleven-year-old Wladyslaw Moes’s limpid gaze? Whichever, it was almost certainly these age differences to which he was alluding when he spoke of wishing to demystify his work.

Mann, of course, never did write Death in Venice over again. Nor, ever more Olympian and aloof, did he trouble to ascertain who precisely was the little Polish boy on the beach of the Lido or what might have become of him.

In fact, bizarre as it may seem, little Adzio grew up in Poland as ignorant of, and indifferent to, the role which he had unwittingly played in Mann’s masterpiece as, it appears, was the entire Moes family. The novella was almost immediately translated into most European languages, including Polish; yet it was not until twelve years later, in 1924, when Wladyslaw Moes was in his own early twenties, that one of his cousins finally read Death in Venice. Taken aback by the story’s references to an aristocratic Polish family staying at the Hôtel des Bains, to the amusingly vulgar musicians who had been hired to entertain the resident clientele, and the insidious rumors of cholera that had started to circulate through the city, taken most aback by the narrative premise of an elderly voyeur entranced by the spectacle, on the beach of the Lido, of two extremely personable young boys at play, boys whose nicknames, moreover, Tadzio and Jaschiu, were disturbingly reminiscent of Adzio and Jas, she naturally showed the book to her nephew. Adzio was amused, perhaps flattered; but for the moment a handsome young man leading an easy, affluent life, he was not terribly interested. In any case, he never chose to identify himself to Thomas Mann.

Gilbert Adair has written five novels, including The Holy Innocents (which Bernardo Bertolucci is making into a film), a verse parody of Pope entitled The Rape of the Cock, and assorted nonfiction.

Discussion2 Comments

A very interesting article about the book and Mann’s real life experience.

I came upon this after reading through numerous comments on a film titled “The Most Beautiful Boy In The World” (which I have not seen). The film is about the life of Bjorn Andressen who was cast as Tadzio in the film version of Mann’s book. It seemed obvious to me that quite a few of those commenting on the film “Death in Venice” had not read the book – and perhaps also had not heard of Mann.

Quite a few comments focussed on what the viewer (comments) inferred as the sexual interest of Aschenbach in Tadzio. This was roundly condemned in many comments as disgusting and was referred to as paedophilia.

In fairness to those commentators it should be said that the direction that Andressen received by Visconti in his role as Tadzio in the film often seemed to imply a knowing awareness of a darker motive for Aschenbach’s interest than Mann had probably expressed or even intended in his book. Although the above article certainly suggests that Mann’s wife Katia was aware of his interest (sexual?) in young males.

In the fourteenth paragraph is a major factual error, if I am reading it correctly. In listing the differences between Mann’s 1911 trip to Venice and Aschenbach’s in the novella, Adair states “…Aschenbach has an estranged daughter, Mann was not yet a father…” At the time of the trip to Venice, four of Mann’s six children had been born.