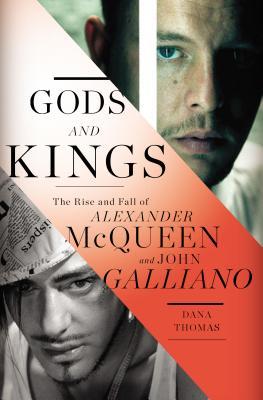

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of

Gods and Kings: The Rise and Fall of

Alexander McQueen and John Galliano

by Dana Thomas

Penguin Press. 422 pages, $29.95

IN THE POPULAR MIND, male fashion designers, like flight attendants, hairdressers, and interior decorators, are assumed to be gay, and not without reason. A few names come to mind: Balenciaga, Dior, Givenchy, Cardin, St. Laurent, Lagerfeld, Valentino, Dolce and Gabbana, Armani, Versace, Franco Moschino, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Halston, Bill Blass, Calvin Klein, Geoffrey Beene, Stephen Burrows, Clovis Ruffin, Tom Ford, Michael Kors, Marc Jacobs, Isaac Mizrahi—not to mention the legendary Charles James, who, rumor had it, used to fit his dresses on Puerto Rican boys in his room at the Chelsea Hotel. Yet no one has written about the strange symbiosis between gay men and the straight women who wear their clothes, go to their fashion shows, write about them, and find an excitement in the fashion industry that may mystify non-fashionistas, but certainly surpasses, for some of us, anything that happens in the NFL.

Dana Thomas’ book is about two gay British designers, John Galliano and Alexander McQueen, and their remarkably parallel careers. Both were gay sons of working-class families—Galliano’s father was a butcher, McQueen’s drove a cab—and both were bullied for being sissies when they were growing up. Both had mothers who supported their interest in clothes. Both went to an arts school in London called Central Saint Martins. Both went to gay clubs—McQueen to a place called Man Stink. Both were

helped by aristocratic women who spotted their talent. Both were hired by Bernard Arnault, the French billionaire who built the luxury conglomerate LVMH, to head famous fashion houses. Both became the fashion equivalent of rock stars, with more money than they knew what to do with, chauffeured cars, apartments in Paris, and total creative freedom. Both were under incredible pressure to design more collections per year than any human being should be asked to (pace Karl Lagerfeld). Both had boyfriends who didn’t last, including, in McQueen’s case, a man he “married” before there was such a ceremony and who, he later claimed, infected him with HIV. Both abused drugs. And both eventually cracked under the pressure—Galliano by telling a woman during a drunken rant in a Paris café that she had “an ugly Jew face,” McQueen by hanging himself in his closet not long after his muse, Isabella Blow, drank weed killer, and his mother died of cancer. (To complete the fatal daisy-chain, McQueen’s ex-husband committed suicide a month after McQueen.)

Gods and Kings is that peculiar paradox—terrible lives that are fun to read about. Fun because we get to watch both men start out as working-class club kids and end up as huge successes. Fun because, after McQueen sold his company to Gucci for $25 million, he chartered a jet one night to fly with his boyfriend to Spain for cocktails, Paris for dinner, and Amsterdam for clubbing. Fun because he took another boyfriend to Africa after buying all the first-class seats in the upstairs lounge of a 747 so they could be alone. Fun because Galliano, who began each day by jogging through Paris with a professional trainer, got his idea for his infamous hobo-inspired fashion show from the homeless men he passed under the bridges. Fun because, when Bernard Arnault called Galliano in after hearing reports of his drinking and told him he had to enter rehab, Galliano stood up, opened his shirt, and said: “Does this look like the body of an alcoholic?” Fun because McQueen “bought the huge Swarovski chandelier he saw in the Four Seasons George V lobby for 30,000 pounds—just so he could use the crystals to decorate his Christmas tree back home in London.” As Andrew Leon Talley, the Vogue editor, put it: “The divadom. The divadom.”

Divadom is fun to read about even when it isn’t. This book is filled with self-destruction, disloyalty, megalomania, betrayals, overdoses, and cocaine. (“He was spending 600 pounds a night,” a friend of McQueen’s said. “He had five dealers.”) Isolation seems to have gone along with grandeur. Galliano would deal with the pressure by refusing to get out of bed, even on the day he was invited to Buckingham Palace to be given an award by the Queen. The more down-to-earth McQueen was all alone at the end when he attempted suicide, first by slitting his wrists and, when that failed, by hanging himself from the shower head, and after that buckled, from the pole in his closet. (Bingo.) The two men’s lives confirm every cliché about fashion one has ever entertained, including, in McQueen’s case, the obligatory trip to India and the dalliance with Buddhism—the search for peace with which Charles Ludlam opened his play about the very gay fashion designer Claude Caprice.

Caprice seems to have been the bane of the two men’s existence—not just their own whims, but the passionately judgmental audience at their fashion shows, who wanted to be astonished, amused, moved to tears, and transported by a new way to dress. Thomas’ descriptions of these shows are like the recreations of long-forgotten Broadway shows that we remember only for their songs, which can be tedious because she leaves nothing out: where they got the theme, who did the music, hair, makeup, hats, accessories, and lighting, and who was in the front row. (That said, go to YouTube and watch McQueen’s The Horn of Plenty show, and you may understand why this book was written.) Both McQueen and Galliano created narratives for the collections they were showing (“a ravished Russian royal named Princess Lucrecia who flees from danger at home to Scotland. … She’s a very sensuous woman, in complete control of her own destiny”). In the old days, at Christian Dior, collections were shown to clients by models who entered the room with a little card bearing the number and name of the dress. By the time Galliano and McQueen were hired, the fashion show had become a theatrical production where props, venue, special effects, and music could cost millions of dollars.

If haute couture was the province of rich women who went to Paris to be fitted for gowns in the 19th century, by the latter half of the 20th, according to Thomas, businessmen were buying up the individual fashion houses and folding them into conglomerates. (Exactly what has happened to publishing.) The idea was to turn the individual ateliers into brands whose glamour would sell handbags and perfumes, where the real money is made, since by the 1970s very few women were buying haute couture. What made the designer-as-rock-star worth his salary for Arnault was the sale of accessories—in McQueen’s case, just a scarf with his logo (a skull) on it. A million dollars for a fashion show got Dior 25 million dollars in publicity. There was no such thing as bad press—until Galliano’s meltdown. In short, what the “gods” (the business tycoons) did was to use the “kings” (Galliano and McQueen) to imbue Givenchy and Dior with enough glamour that the brand could go on after the designers had vanished.

But it was all about sex. “My goal,” Galliano said, “is really very simple: when a man looks at a woman wearing one of my dresses, I would like him basically to be saying to himself, ‘I have to fuck her.’ I think every woman deserves to be desired. Is that asking too much?” McQueen said he wanted women in his clothes to feel powerful, not abject—though when he introduced “the bumster,” which was nothing more than pants cut so low in the back that the ass-crack showed, you’d think, reading this book, that he had discovered radium. (He also spoke of something called “the cuntster.”) McQueen was admired for the technical skills he honed as a tailor on Savile Row—he won over the staff at Givenchy when he installed a sewing machine next to his desk. Galliano was praised for his theatrical imagination. Both men were charged with “degrading” women when their shows bombed, accused—as gay men have often been—of misogyny. On the other hand, when the audience loved the new collection, it was extremely emotional. Jesus—if not Anna Wintour—wept.

There was, of course, a dark side. “I love what I do,” McQueen said, but after seeing a TV documentary on Thomson’s gazelles, he remarked: “I watched those gazelles getting munched by lions and hyenas and said, ‘That’s me!’ Someone’s chasing me all the time, and if I’m caught, they’ll pull me down. Fashion is a jungle full of nasty, bitchy hyenas.” “He knew,” said one of his assistants, “that success was going to take so much effort to maintain that one day he would be like every other famous artist and have a dip in popularity. That scared him, the fear of going out of fashion.”

Most people will never encounter the world this book is about unless they watch the red carpet at the Oscars or walk into a Walgreen’s and find Isaac Mizrahi’s name on a box of Kleenex. But at the heart of all these consumer objects is the glamour associated with Paris, and at the heart of that is the old idea of romantic genius—even if, in McQueen’s case, it resided in a gay man who had issues with his weight. Throughout Gods and Kings, the author, like most fashion critics, makes a distinction between a designer and an artist. Galliano was hailed for bringing fantasy back at a time when fashion had gone minimalist (Halston, Calvin Klein, Armani). McQueen apparently did something more. “The word ‘artist’ is thrown about recklessly in fashion,” Thomas writes, “but here it felt apt. This kid, not yet thirty, wasn’t just making clothes. Nor, like Galliano, was he making costumes. He was using fabrics and embellishments to create something that took our breath away, the perfect meeting of color, perspective, texture, and shape—something truly sculptural—that happened to be worn. McQueen was indeed an artist, a natural-born one with a clear and informed vision, and his work now was bordering on genius.”

But what sort of genius? A terrible folie de grandeur, an awful hubris, runs through the story of these two men’s ascent, or descent, into divadom. As one of McQueen’s boyfriends said after his death: “He had researched Marilyn Monroe’s suicide in detail. … He said to me, ‘As I was powerful in life, I will be a god in death. And gays don’t do old.’”

No doubt years ago a book like this could not have been written; there would not have been a word about the designers’ private lives, or the gay clubs in London where they first practiced their art. Galliano and McQueen were simply gay men who loved making dresses. (Both designed a men’s line as well, though menswear for some reason resists change—otherwise we’d all be in kilts.) But they got caught up in a brutal circus created in large part by the media. Thomas’ book reads like the story of Icarus, or Suddenly Last Summer. Amid the jacquard, chiffon, and gazar, the two men seem to have been sacrificed on an altar whose meaning is not quite clear. You may say it was just their own bratty behavior or the temptations put before two boys of working-class origins who suddenly found themselves with Paris apartments, chauffeurs, and all the drugs they wanted. Thomas’ thesis is simple: “In the mid-1990s, luxury fashion experienced a seismic shift from the business of creation to the business of hype.” McQueen was always ambivalent about his profession, a struggling soul who seems to have had a conscience as troubled as his ambition. Before he died, he was trying to move to San Francisco to teach. Galliano simply withdrew, with the help of an assistant who was an all-too-effective gatekeeper, according to friends—an assistant who added to the awful body count by dying of a heart attack while bingeing on cocaine. There are almost as many corpses onstage at the end of this book as there are in Hamlet.

What does it all mean? Leafing through an issue of the fashion magazine W in a doctor’s office not long after reading this book, I came upon an ad for Alexander McQueen (whose line is now designed by his assistant Sarah Burton): on one page a dress, on the other a handbag. How much, I could only think, lies behind that purse! It’s easy to make fun of fashion journalism when it gets too intellectual about clothes—like the piece The Washington Post ran a few years ago about the significance of Michelle Obama’s boots, which sounded like a graduate student applying Foucault to footwear. Dana Thomas’ book is like a long article in Vanity Fair: all narrative, all dish. But the problem is that Galliano and McQueen are such individual cases that they overwhelm her central thesis, which is that tycoons like Arnaud crushed what was once a world of individual creativity under a juggernaut of international merchandising.

This dish-filled nightmare makes it hard to decide whose ego was greatest—the women wanting to be powerful and desirable, the gay boys behaving like divas, or the Svengali behind them all, Bernard Arnault, whose Gehry-designed museum of contemporary art, that Medici-like gift to the people of Paris, just opened in the Bois de Boulogne. One can’t decide whether Gods and Kings is about the horrors of consumerism or two gay Brits who experienced the catastrophe of success. Whatever the answer, it makes one wish the whole business would shrink, subside, and return to what it used to be. (Couture means simply “sewing.”) At his last show for Givenchy, the audience was moved when McQueen came out to take his bow with two women: the heads of the ateliers that had made the clothes. What no one could know, of course, was the amount of human wreckage still to come. Gods and Kings makes House of Cards look like Leave It to Beaver.

Andrew Holleran’s novels include Grief and The Beauty of Men.