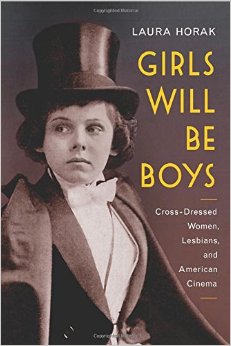

Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-Dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934

Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-Dressed Women, Lesbians, and American Cinema, 1908-1934

by Laura Horak

Rutgers. 311 pages, $29.95

EVEN IN ITS TITLE, Girls Will Be Boys sets out to correct past takes on cinematic representations of cross-dressing. Most of the writing about the issue has focused on men dressed as women. Laura Horak’s highly insightful book doesn’t neglect that phenomenon, but its main focus is cinematic moments when women dressed as men, and in this respect it manages to upend a lot of conventional wisdom. Indeed, even for those well-versed in depictions that challenged traditional gender roles, Horak’s book will be an eye-opening examination of a tradition that’s far more complex than previously thought.

Horak begins by identifying the most iconic moments of female-as-male cross-dressing: Marlene Dietrich in Morocco (1930), Greta Garbo in Queen Christina (1933), and Katherine Hepburn in Sylvia Scarlett (1935). These are often presented as among the few examples of such cross-dressing in early cinema, and they’re often cited in film history books. Horak argues that this is a perception of history that’s as misguided as it is widely held: “Where previous accounts have identified only thirty-seven silent American films featuring cross-dressed women, I have discovered more than four hundred.”

Further, Horak points out not only that cross-dressing in silent movies was much more common than previously thought, but that it wasn’t perceived as particularly transgressive or threatening. That’s because in the cinema’s early years it was taking many of its cues from the theater, and in that milieu women or girls filling male roles was an accepted casting choice and far from unusual.

The girls-as-boys casting call became threatened early on due to the evolution of American cinema, which became more invested in realism and began to pull away from its theatrical roots. While having a female play a male role worked well on the stage—where disbelief is routinely suspended—this became far less acceptable for screen actresses. Horak outlines how journalists admired actress Marie Doro’s impressive drag act in the 1916 film Oliver Twist, in which she played the titular character. They pointed to how clever the illusion was, but later on, such gender switches that were common in the theater went out of vogue in films. (At this juncture, film historians will shudder in horror: Horak culled her visual material for Oliver Twist from a magazine article that was promoting it; all known copies of the 1916 feature have been lost.)

By the late 1920s and early ’30s, the moral crusaders had moved in, and images of women dressed in male garb were causing panic among studio execs. Studio head Jack Warner told a Los Angeles Times reporter in 1933 that the “trend toward mannish attire for women is a freakish fad” and that “we have refrained from showing any women dressed as a man in our pictures.” He concluded with a quote that says as much about the oppressive star system (in which studios had stars on strict contract, effectively owning them) as it does about Hollywood’s homophobia: “The order becomes effective immediately and our feminine stars have been warned that they must stay feminine.”

This growing backlash against cross-dressing, equating pants with perversion, grew stronger after 1934 with stricter enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code or “Hays Code” (no relation) and the emergence of moral crusaders to see that it was. Stars who dared to cross gender lines found themselves under scrutiny by the press. Horak cites one absurd moment when journalists were attempting to raise doubts about one star’s persona by analyzing her home decoration choices: one reporter noted that Garbo “likes solid substantial furniture and hates feminine geegaws,” while another described her home as devoid of any “feminine appointments … the furnishings are solid and mannish.”

Horak’s exhaustive research turns up many incredible moments in the history of gender shake-ups in the movies. Girls Will Be Boys is a hugely satisfying read, one of those rare books that offer distinct value to scholars while simultaneously being an entertaining read. It’s also another reminder of the bizarre mass of contradictions in the Hollywood dream factory: a place full of liberation and titillation, countered by the forces of censorship, moral panic, and repression.

Matthew Hays teaches film studies at Marianopolis College and Concordia University in Montreal.