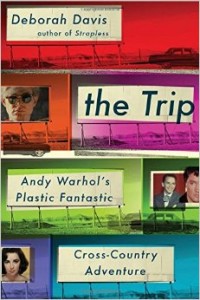

The Trip: Andy Warhol’s Plastic

The Trip: Andy Warhol’s Plastic

Fantastic, Cross-Country Adventure

by Deborah Davis

Atria Books. 336 pages, $26.

IN THE SUMMER OF 1963, Andy Warhol and three friends—the young poet and Warhol’s handsome assistant Gerald Malanga, filmmaker Taylor Mead, and painter Wynn Chamberlain— packed into Chamberlain’s Ford Falcon station wagon and drove from New York to Los Angeles. Andy didn’t own a car, or a driver’s license. For much of the trip, he lounged on a mattress placed in the back of the station wagon and watched the landscape and brilliant colors of the billboard advertisements pass by while perusing celebrity magazines. Deborah Davis suggests in The Trip that this experience—with its roadside motels, silver diner meals, brightly colored billboards, and neon lights, all bathed in an Americana patina of mid-century kitsch—would prove a turning point for Warhol and Pop Art.

The four were in a rush to get to the coast for the opening of an exhibit of Warhol’s painting at the Ferus gallery and, more importantly, a party that actor Dennis Hopper and his first wife Brooke Haywood were hosting for Warhol. Hopper and Haywood had admired Warhol’s work ever since they encountered his “Campbell Soup Can” canvases at his first exhibition at the Ferus gallery in 1962. Warhol was more than excited to be the center of a real Hollywood party. While he was already successful and wealthy from a decade in advertising illustration—he owned a townhouse on the Upper East side, where he lived with his mother Julia—his place in modern history had yet to be established. Many collectors and critics viewed Warhol’s canvases with their bright colors and commercial subjects with suspicion, seeing him as an odd interloper to abstract expressionism, which still dominated art journals and gallery shows.

Davis has a knack for turning historical events into breezy passages, illuminating a constellation of personalities and social dynamics within a tightly focused narrative. In Party of the Century, she luxuriated in the gossip and details of Truman Capote’s 1964 Black and White Ball. Similarly, in Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X (2003), she focused on the social scandal following Sargent’s sexually suggestive portrait of the American expat and society celebrity Virginie Gautreau in late 19th-century France. In these histories, Davis gave us compelling and fast-paced stories that simmered with the paradoxes of fame and celebrity.

Davis has a knack for turning historical events into breezy passages, illuminating a constellation of personalities and social dynamics within a tightly focused narrative. In Party of the Century, she luxuriated in the gossip and details of Truman Capote’s 1964 Black and White Ball. Similarly, in Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X (2003), she focused on the social scandal following Sargent’s sexually suggestive portrait of the American expat and society celebrity Virginie Gautreau in late 19th-century France. In these histories, Davis gave us compelling and fast-paced stories that simmered with the paradoxes of fame and celebrity.

These themes anchor The Trip as well, though Davis turns what is often a footnote in Warhol’s biography into a life-changing event early in his career. These momentous changes she finds in the minutiæ of the trip, as Warhol, well known for his packrat habits, kept nearly every receipt and scrap of paper from the journey that summer, giving Davis an unconventional chronicle of where they went and what they did. She was also aided by the recollections of Malanga. Finally, she retraced their steps by driving the same route from New York to L.A., though she never develops this line of research, omitting whatever insights she may have gained from her trek across contemporary America.

The book itself has all the distractions of a road trip, with detours every so often to detail the backstories and historical trivia about personalities and products. We learn about the origins of credit cards in the 1950s, as Warhol had a newly acquired Carte Blanche, which he used as often as possible, diligently consulting the register of hotels and restaurants that accepted the card. We get a brief history lesson of the photo booth from its origins as the Photomaton in 1920s Times Square. When the wealthy art patron and collector Robert Scull called on Warhol to do a portrait of his wife Ethel in 1963, he took her to a photo booth in Times Square and fed the machine a hundred dollars worth of quarters. From the resulting stack of images, he created a series of silkscreen portraits arranged in five rows of seven and called it Ethel Scull Thirty-Five Times. Scull was ecstatic. Notes Davis: “it made her look—and feel—like a movie star.”

And there were other side trips. We learn about the origins of the federal Interstate highway system in the 1950s and ’60s, and how Warhol and friends took the now iconic Route 66 from Chicago to L.A. just as that two-lane road was becoming obsolete. With its attractions and oddities, Route 66 was at root “conceived to make money,” Davis remarks. The highway was filled with billboards advertising a host of modern products that flashed past the car windows as Warhol reclined in the back. Davis imagines Warhol’s fascination: “America … was a gallery of enormous images, and it was all now! To him, this was the new art.”

We also get this intriguing historical fact: the Ford Falcon that carried the group across the country was the idea of Robert McNamara, who in the 1950s was a vice president of Ford Motors. The Falcon offered a smaller, compact car for American drivers and especially for export overseas. With the success of the Falcon, McNamara was promoted to president of the company, only to resign two months later to become Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense. As Davis writes, “By 1963, McNamara was ensconced at the Pentagon, masterminding the war in Vietnam, with Detroit a distant memory.” One wishes he stayed with Ford.

These fascinating historical currents run through the book and enliven the cultural context that Davis maps out. However, The Trip offers few new insights into Warhol himself. Instead, the journey largely confirms our understanding of Warhol’s eccentricity, his fascination with celebrity culture, and his increasingly elusive persona as he redefined himself from advertising illustrator to Pop Artist in the early 1960s.

One major flaw concerns the way that Davis deals with sex—which is often to ignore it, a quality I thought was strange for a book about four young men traveling cross-country in the ’60s. Davis mentions an unrequited flirtation between Warhol and the handsome Malanga, but leaves it at that. She does note that the gregarious Taylor Mead kept the group entertained with his travels in California and the Midwest, conjuring stories of Beat hangouts and poetry readings, as well as his sexual exploits. On their many stops for gas, Davis writes: “Taylor had a knack for persuading handsome young gas jockeys—guys who were absolutely straight—to accompany him behind the building for a quick session of oral sex. They were ‘trade’ in the strictest sense of the word.” How Davis knew that they were “absolutely straight” is not entirely clear; but this brief story is meant more to illustrate Taylor’s personality than the sexual exploits that were possible in mid-century America. Warhol, Davis claims, was both “intrigued and annoyed” by Taylor’s antics, adding that “he was jealous that Taylor was getting so much action in unexpected places and might have wished they could have traded places, but he was in a hurry to get to California and counting every wasted minute.”

Once in L.A., the opening night went well, though few works were sold. The party at the Hoppers’ house was filled not only with L.A. art world personalities but also a host of movie stars, including what Davis terms the “most impressive sighting of the evening … the tabloid couple of the moment, Troy Donahue and Suzanne Pleshette,” adding with emphasis “in the flesh.” Davis conjures the excitement that Warhol must have experienced in the presence of celebrities that he’d only admired in magazines.

During his sojourn in L.A., Warhol had an idea to make a short, campy film called “Tarzan and Jane Regained … Sort Of,” with the skinny and awkward Taylor playing Tarzan. Back in New York, the film played at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative in Manhattan and garnered some critical attention. The film was one of many he was working on in the early ’60s, experiments that would later turn his artistic focus away from the canvas for a time.

On their return to New York, Warhol and company spent an evening in Las Vegas. Warhol was fascinated by the dazzling neon lights of the strip. Strangely, at that same moment French artist Marcel Duchamp was also visiting the city, though there’s no indication that the two men crossed paths. Duchamp called the city a “wonderland” even as he was stunned by the “authentic” American-style Folies Bergère performance he attended. As with Duchamp, it was the light and architecture that attracted Warhol the most. Davis notes, for Warhol the city felt like “one fabulous Pop Art museum.”

A year after his Hollywood adventure, Warhol would move into a new, large warehouse studio on the East Side that he named the Factory—a word that evoked, among other things, his working-class roots in Pittsburgh. Davis suggests that the Factory was Warhol’s answer to Hollywood, a “counterculture MGM” with actors, artists, and an assortment of “addicts, hustlers, and other underground personalities.”

What we get in The Trip is a fast-paced biography of Warhol from his Pittsburgh childhood to his death in a New York hospital, with the cross-country journey sitting at the center of this story. Davis shows us how that moment in the summer of 1963 can illuminate much about how Warhol became Warhol. She also reminds us of the cultural context for the artist’s development. Just a few months after Warhol’s return to New York, Kennedy was shot in Dallas, and the Technicolor world of postwar America would soon metamorphose into the realities of war and social protest. “After the assassination,” writes Davis, “the country would never be the same, and after the autumn of 1963, neither would Andy.” Warhol would be inspired to turn the tragedy into art with a series of silkscreen images of Jackie Kennedy taken from Life magazine and stills from the famous Zapruder film footage. Davis gives us a story as much about Pop Art’s elusive icon as it is about the era that shaped him.

James Polchin teaches at New York University and is a frequent contributor to this magazine.