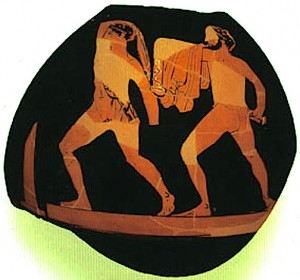

WHENEVER I give a GLBT tour at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, I always stop to talk about this fragment from a red-figured Greek vase. It’s not much to look at, and certainly a casual observer would see nothing homoerotic about it.

WHENEVER I give a GLBT tour at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, I always stop to talk about this fragment from a red-figured Greek vase. It’s not much to look at, and certainly a casual observer would see nothing homoerotic about it.

What you see are two men with drawn swords, presumably facing an opponent off to the left. The one to the left is a beardless youth with his sword raised over his right shoulder in a slashing gesture. The right-hand one is a bearded adult with his sword drawn back for a forward thrust; he is using his cloak to mask his intentions. And that would seem to be that. But anyone who knows ancient Athenian culture and art would recognize at once that these are two of the greatest gay heroes of all time: Harmodius and Aristogeiton. We hear about them from both of the first historians, Herodotus and Thucydides, as well as in Plato’s Symposium, among many other places.

Why all the fuss? Harmodius and Aristogeiton were lovers who in 514 BCE assassinated Hipparchus, the brother of Athens’ tyrant Hippias, and—though historians claim this was a private revenge killing and preceded the end of the tyranny by several years—they were regarded by the Athenians as the founders, or at least the patron saints, of Athenian democracy. It would be hard to  exaggerate the level of adulation they received—posthumously, because they were killed by the tyrant’s guards. They were seen as heroes and as demigods, and blood sacrifice was performed at the spot in the city’s common grave where they were buried. Their descendants were provided for by the city. And they were the subjects of the first statue ever erected in the Athenian agora of human beings (as opposed to gods). A double statue of them was erected in the Agora early in the democratic period. When the Persians invaded in 490 BC, they took the statues to Susa, but the Athenians responded by erecting a second pair.

exaggerate the level of adulation they received—posthumously, because they were killed by the tyrant’s guards. They were seen as heroes and as demigods, and blood sacrifice was performed at the spot in the city’s common grave where they were buried. Their descendants were provided for by the city. And they were the subjects of the first statue ever erected in the Athenian agora of human beings (as opposed to gods). A double statue of them was erected in the Agora early in the democratic period. When the Persians invaded in 490 BC, they took the statues to Susa, but the Athenians responded by erecting a second pair.

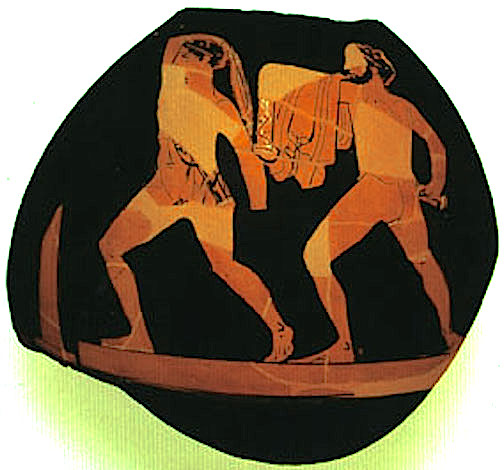

The original statues, like almost all Greek bronzes, have disappeared, melted down for weaponry at some point in late Antiquity. But we have a remarkable amount of evidence for how they looked. There are a number of pieces of Roman copies, and a well-preserved marble copy in the Naples Archaeological Museum, which you can see here (or in the flesh, as it were, on Oscar Wilde Tours “Gay Italy, from Caesar to Michelangelo and Beyond” tour this October!). This is a fancier piece of art than the Boston vase fragment, but the heroes are in the same positions. They are the perfect role model for the Athenian citizen—permanently ready to assassinate a tyrant. In all versions they’re portrayed as a male-male couple—exactly the kind of bond that the Greeks associated with courage in battle. As the Pausanias says in Plato’s Symposium: “Even the tyrants of this city learned this (that Eros instills loyalty) by experience: for the steadfast love of Aristogeiton and Harmodius destroyed their power.”

To learn more about gay history and culture in world art, come on one of Oscar Wilde Tours’ tours! Visit www.oscarwildetours.com for more information.

Andrew Lear is the founder of Oscar Wilde Tours.

Discussion1 Comment

Pingback: Gay Heroes of Ancient Greece - Oscar Wilde Tours