IN A NATIONAL REFERENDUM on May 22, Ireland became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, not by judicial or legislative action, but by a popular vote. How did a country long assumed to be a conservative Catholic stronghold, which only decriminalized homosexuality in 1993, become the first to take this course of action?

IN A NATIONAL REFERENDUM on May 22, Ireland became the first country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage, not by judicial or legislative action, but by a popular vote. How did a country long assumed to be a conservative Catholic stronghold, which only decriminalized homosexuality in 1993, become the first to take this course of action?

At final count, the vote was 62 to 38 percent in favor of marriage equality, a spread of almost 25 points. As surprising as the magnitude of the result was the breadth and depth of the vote, which swept up not only the liberal suburbs of south Dublin but also the working-class suburbs north of the city and across the rural center of the nation. High voter turnout played a role, especially among young voters, as did a massive wave of migrants returning home to vote. But the biggest factor was undoubtedly the Catholic Church’s loss of moral authority following a series of clerical abuse scandals in the early 2000s.

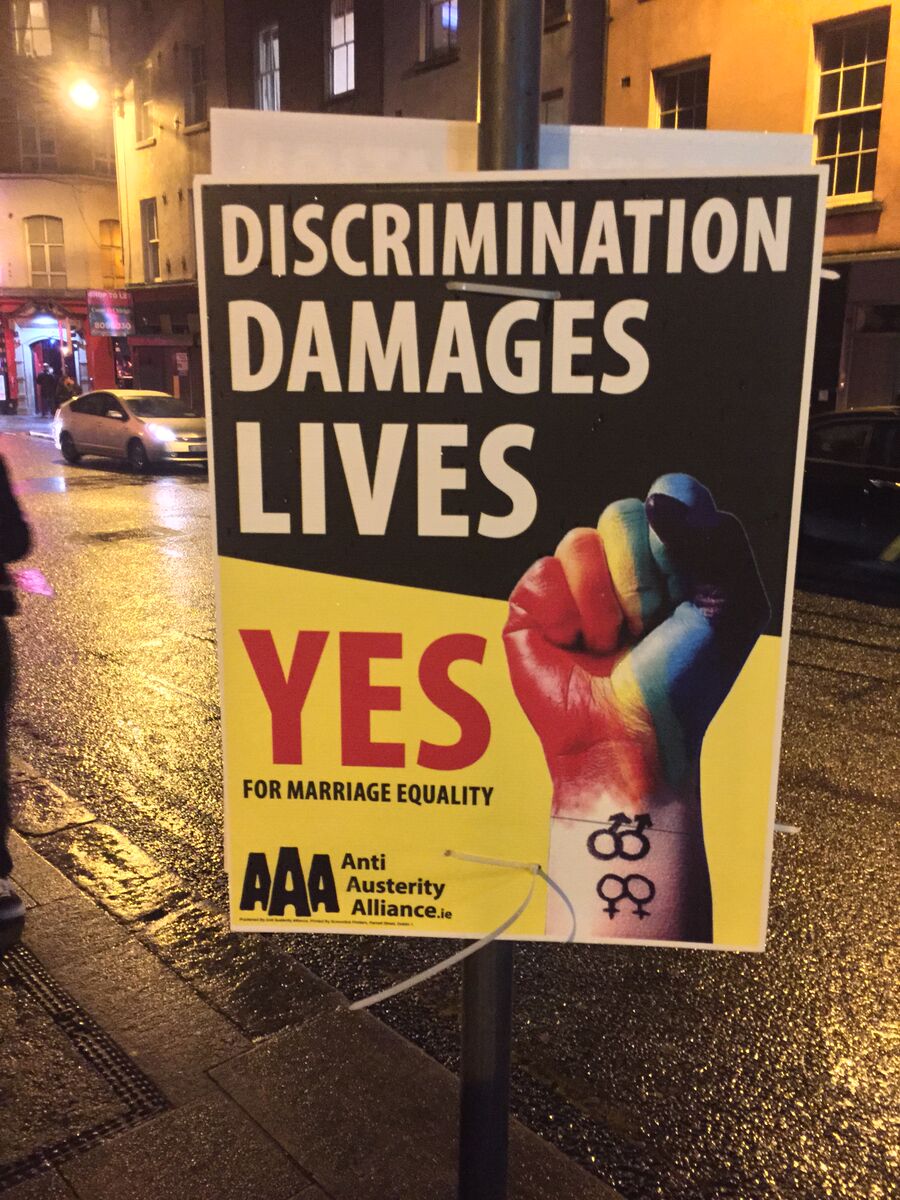

A major factor was the way in which working-class voters, who are generally conservative on social issues, mobilized around the call for “equality” after being politicized by recent austerity politics. In Ireland, “the usual left critique of marriage politics doesn’t fit,” wrote Anne Mulhall of University College Dublin, “because most people weren’t really voting on marriage equality.” If the constitutional question was marriage, the vote was never simply that. Explains Mulhall: “In the end the referendum came to be about whether or not people accept lgbtq people as fully human.”

In a similar vein, Irish novelist Barry McCrea said the vote was not “about couples and weddings but about equality and inclusion. Now Irish gays and lesbians of my generation will no longer have the lurking fear that they are secretly despised and feared by most of their fellow citizens, and younger generations will no longer grow up with the feelings of exclusion and self-hatred.”

Irish Times political commentator Fintan O’Toole offered a similar interpretation: “There’s no ‘them’ anymore. LGBT people are us—our sons and daughters, mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, neighbors and friends. We were given the chance to say that. We were asked to replace tolerance with the equality of citizenship. And we took it in both arms and hugged it close.”

In its closing months, the marriage campaign seemed more a people’s movement than a top-down initiative. Even though the political parties and national leaders supported the measure, the campaign was driven by grassroots organizing—by young people who went back to their home towns to campaign door-to-door, by older couples speaking out in forums on-line in support of their lesbian and gay children. Perhaps more than anything else, the vote was the culmination of twenty years of Irish men and women coming out to their friends and families and making homosexuality personal and real.

One upshot of the vote may be to discredit the insistent use of the “will of the people” chestnut by anti-gay politicians in other countries who argue that activist courts and judicial fiat have thwarted public opinion. Recent polls in the U.S. suggest that a growing majority of Americans support marriage equality—a reality that politicians may find it that much harder to deny.

The Irish vote was a decisive repudiation of the Catholic Church as an entrenched system of oppression and social control, and this may be the referendum’s most far-reaching effect, as it suggests a rejection of repressive moral authority and an embrace of authentic social change. Like same-sex marriage, divorce became legal in a constitutional referendum (in 1996), though the margin of victory was very slim, after a previous referendum had failed in 1986. Both initiatives were vigorously opposed by the Church.

In the wake of this victory, Mulhall suggested that the question now is “how to resist the impetus from the political mainstream, straight and GLBT, to say that ‘equality’ has now been achieved.” As I write, the U.S. Supreme Court was poised to announce its decision on same-sex marriage. Regardless of the outcome, GLBT people in many states can still be legally fired for being gay; sexual minority youth still face bullying and homelessness; “ex-gay therapy” is still legal in 48 states. Marriage equality won’t fix these problems, though it can help reshape a culture that allows these injustices to exist. Both here and in Ireland, the Irish vote can offer a context for thinking differently about achieving equal rights.

Ed Madden is director of the Women’s and Gender Studies Program and an associate professor of English at the University of South Carolina.

Discussion1 Comment

The old conservative right wing has to take a step back from the new wave of liberalism that is sweeping the world. Ireland will profoundly influence the neighboring countries of the UK until all English speaking countries legalize same sex marriage. The greatest sign of equality is showing that you accept and respect all sexual minorities so that no exclusion from mainstream living ought to be recognized. Ireland is making it possible for gays and lesbians to experience the same quality of life that is deserved of everyone. It is time once again to see how the papacy reflects on this government decision to legalize all same sex relationships.