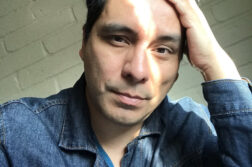

I first encountered Sarah Schulman in January 1997, when she was a speaker at “Literature in the Age of AIDS” in Key West. That was a world ago. We met again a couple of years later at UNC-Asheville, where she was beginning to articulate her ideas about “familial homophobia,” the central idea in her remarkable book Ties That Bind.

Schulman has spent her whole adult life as a journalist, novelist, playwright, and activist. In 2016, she has two new books, a novel called The Cosmopolitans, which came out in the spring, and the powerful nonfiction book Conflict is Not Abuse, due out October. Hugh Ryan recently wrote a long retrospective piece on Schulman’s body of work for the Los Angeles Review of Books. In assessing the power of her voice, he observed that Schulman “places a high premium on accountability, responsibility, and consistency, and it shows in the way she chases an idea from book to book, from nonfiction to fiction and back again.” Ryan’s insight is spot on. Schulman is a public intellectual, an artist, an idea maker; she does not shy away from controversy and does not seek the spotlight. For me, her integrity as an artist and a citizen makes her a singular presence in American (queer) culture.

This interview was conducted in April in West Hollywood.

Chris Freeman: You are a distinguished professor, an author, an activist, but you had an unconventional education for someone in your professional position.

Sarah Schulman: I had an excellent public school education at Hunter High School, which was at the time a school for smart girls. Elena Kagan was a year behind me, but we were in student government together. Then I went to the University of Chicago, where I was a terrible student. I dropped out. After Chicago, I went to Hunter College, where Audre Lorde was my teacher, and I finally got my BA from Empire State College. But at Chicago, I had a class on 19th-century French realism. Balzac’s novel Cousin Bette stuck with me all these years, and it showed up again for me in 2003 in a play called “The Burning Deck” that I wrote for the La Jolla Playhouse. The play was expanded into The Cosmopolitans.

CF: While you’ve been an artist and writer since your twenties, it looks to me as if you’ve been an activist all your life.

SS: I came back to New York in 1979, and two important things happened around that time. After leaving Chicago, I went to Europe (with my student loan money) and was involved with an illegal abortion situation, not for myself, but for a friend. When I came back to the United States, the Hyde Amendment had just passed, which attempted to limit women’s rights to abortions, so I got involved in fighting that immediately. I became a member of CARASA (Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse). I was part of a protest at Congress, a direct action. With the Women’s Liberation Zap Action Brigade, I disrupted a Congressional anti-abortion hearing and was charged with “Disruption of Congress.” That is the first time I got arrested. CARASA didn’t like that strategy, and that political difference over direct action was soon followed by other conflicts that resulted in a lesbian purge.

CF: A strange parallel to a decade earlier when the lesbians were kicked out of NOW.

SS: Yes, exactly. And this is coincided with my work for WOMANEWS, a new feminist paper. I covered the radical right (what would become the Tea Party) and the anti-abortion movement for them.

CF: Is that where your career as a journalist really started?

SS: Yes. I wrote for WOMANEWS, Gay Community News, and The Guardian, a hundred year old Marxist paper out of New York, and The Native. They’re all movement publications: GCN was left-wing gay men and women; The Native was for gay men; The Guardian was lefty and almost anti-gay; and WOMANEWS was a feminist paper for gay and straight women. I’m still a journalist. I published a piece in Slate recently on HIV Criminalization.

CF: You started covering AIDS early on.

SS: I did a piece for The Native about the first AIDS case in the Soviet Union in the early 1980s. We had no concept of AIDS as global. That was my first HIV piece. I was a City Hall reporter for The Native. Ed Koch was mayor, and I used to go to meetings and press conference to ask about when we were finally going to have a gay rights bill. And then AIDS started, so I was on that beat already. I covered the closing of the bathhouses for The Native too. The fact that I was assigned to this story reveals how chaotic coverage was. After all, I was not allowed in the bathhouses. Reporters were dying. It was hard to understand what the stories actually were.

CF: You also wrote about AIDS for the Village Voice.

SS: The Voice had two editors who covered AIDS, Robert Massa and Richard Goldstein. Goldstein wrote long, personal pieces; Massa had AIDS and wanted to cover it in a much broader context. He was my real editor, but he was dying. I did the first story on women’s exclusion from drug trials. I had to go to Robert’s apartment when we worked; he was that sick. He died when I was in the middle of a story about pediatric AIDS. I was writing on AIDS in a social context. Goldstein was not interested in these issues. The piece I wrote about double-blind placebo studies with infants and HIV was not something Goldstein wanted to run, so I published it in WOMANEWS. After that, I was no longer part of the Voice. I pitched twelve ideas to The Nation—and I wrote the first story ever on AIDS and homeless people. It appealed to them in part because it was a class or an economic story, not a “gay” story. So AIDS and Social Justice is something I have focused on for more than thirty years, as a writer and an activist. I’m still on that beat. My new book, Conflict is Not Abuse, has a huge section on HIV criminalization.

CF: Your career as an artist was also beginning to gain traction at the same time.

SS: My first novel, The Sophie Horowitz Story, came out in 1984, from Naiad, a lesbian press run by Barbara Grier, who had been the book editor at The Ladder for the Daughters of Bilitis. I had about sixty rejections. I got letters saying that it was so funny, but if only the character weren’t a lesbian. My girlfriend’s other girlfriend was a temp at Scribner’s, and she sent my manuscript on their letterhead, which got the attention of Naiad. They took it, but they didn’t really know what to do with a Jewish novel. The drawing of Sophie on the cover made her look Black. The cover copy said “Sophie is up to her Jewish earlobes in murder and intrigue.” It was highly racialized. The book was read, though. It represented a generational shift; I was part of a generation of lesbian writers who had never been in the closet. So, whereas most previous lesbian literature was a dance between popular culture and a kind of lesbian subculture, the writers of my generation didn’t write that way. For us, lesbians were part of popular culture. So I wrote a detective novel with a lesbian protagonist. Then in 1986, I wrote a book called Girls, Visions, and Everything, which was published by Seal Press. In it, I was responding to the literature of Beat culture in the East Village in 1960’s, but with an 80’s lesbian spin. The next year, ACT-UP was founded and I became part of it, and that same year Jim Hubbard and I founded MIX, the New York Queer Experimental Film Festival. So experimental film, activism, and writing were all part of what I was doing.

CF: In a sense your writing career in the 1980s and 90s was part of the rise, the peak, and the splintering of publishing, both in terms of gay books and of how publishing worked.

SS: Absolutely. My novel After Dolores was published by Dutton in 1988 and was reviewed, by a straight man, in the New York Times. It was a rave review; it was life changing, and I turned thirty that year. This was before niche marketing. The book was translated into eight languages. Mainstream publishers began to acquire lesbian titles; there was a big discussion at the time about big publishing houses versus women’s presses for lesbian books.

CF: Didn’t Dutton publish Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina in 1992?

SS: Yes, and a lot happened in the five or so years between After Dolores and Bastard. Mainly, AIDS, which created a visibility for gay things. The first OutWrite conference was in 1990; queer writing was growing in popularity. Allison’s novel created a quandary for the publishing industry. She was an out lesbian, but her novel did not have lesbian content. This was new. Thus developed a two-tiered marketing program. Bastard was sold as “general fiction,” while people like me became part of “lesbian fiction.” This is when Barnes & Noble started having a “gay and lesbian” section. The review I got a few years earlier in the New York Times would never really happen again, because we were all competing for the very few niched “lesbian” spots in mainstream coverage.

CF: The OutWrite conferences are important documents of this incredible time in queer life and publishing. There is footage on YouTube of you at the San Francisco conference back in 1990, on a panel called “AIDS and the Responsibility of the Writer,” with Essex Hemphill, John Preston, Pat Califia, and Susan Griffin. It is stunning to watch this, seeing each of you in the first decade of the epidemic trying to make sense of it. You talked about your then-new novel, People in Trouble. You said, “I identified for myself the category of “witness fiction.” . . . In writing about something of this enormity, when it surrounds you, it leaves those of us who write about AIDS no possibility of objectivity; nor can there be any conclusiveness, since the crisis around us changes daily. I knew that what I was writing would already be history when it was published.” It is astonishing to watch and listen to this “of the moment” conversation from today’s perspective.

SS: That was the opening plenary of the conference. Essex and John died not too long after that. People were dying right in front of us. I remember Craig Harris, a Black writer, who could barely stand up and was dripping with sweat. Jim Hubbard and I, in working on the ACT-UP Oral History Project, have realized that we as a community have been good at documenting and writing about the heroism of AIDS, but not about the suffering. We have not been able to convey the depth of the suffering.

CF: Some of your AIDS-related writing was published in My American History: Lesbian and Gay Life During the Reagan/Bush Years.

SS: Yes, and that is my first book of nonfiction. It is my journalism from before AIDS, through the epicenter of the crisis. It is about the transformation as I started to understand what was happening. I’m one of the few people who’ve been writing about AIDS from the beginning. It is an enduring relationship for me. With the ACT-UP Oral History project, I’ve conducted 187 long form interviews with ACT-UP members over the past fifteen years. Jim Hubbard and I now know more cumulatively about ACT-UP than anybody.

CF: In 1998, your talk at the literature conference at the University of North Carolina, Asheville was about “familial homophobia,” something you’ve spent more than a decade writing and thinking about. This work culminated in Ties That Bind (2009). I think this is such an important part of your legacy.

SS: I started using first person in My American History, and that was important. Never forget that I’m not an academic. Nobody wanted to publish Ties That Bind. This happens with a lot of my work. It was the very first book to identify familial homophobia. I had to coin that term, because gay people just called it “it.”

CF: How do you approach writing nonfiction? Is it different from fiction for you?

SS: I never write about an ongoing conversation. That is to say, every nonfiction book I write is to initiate a conversation. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. For example, Ties That Bind has not been as widely read as Gentrification of the Mind, but I believe Ties should have been published by a mainstream publisher. When you are the first person to present an idea, it is not easy to get published. Gatekeepers don’t recognize it as what it is: new knowledge.

CF: Gentrification of the Mind is a groundbreaking, insightful book. It helps us understand modern cities, modern ways of thinking and living. You are a kind of case study of urban life: your life for half a century in New York is a record of these cultural shifts. First, where did you get that title?

SS: I gave a talk at the New School in the 1990s with that title, and I kept it. It was kind of a weird talk; basically, I was noticing that people were being mean everywhere. I wanted to know why. The culture was homogenizing. One thing I cited in the original talk was that, in the earlier years, I could call any lesbian, and she’d call me back. I remember a lesbian dance critic named Jennifer Dunning at the New York Times. I called her because two gay people were burned to death in Oregon as part of the anti-gay initiative there. I wanted the Times to cover it; she called me back. I told her what had happened and she did the internal stuff and got it covered. But younger lesbians wouldn’t call me back. Why? Because they had been gentrified. They have rights and privileges that we had not had. They took it for granted, but they theorized it as their own personal triumph, rather than as something that my generation had fought for and won. They didn’t understand why they had the power they had.

CF: I think Gentrification is such a comprehensive book. It’s small but powerful, sort of thesis driven.

SS: I’m realizing that my theme for my entire body of work is, “why are people mean?” It’s the subject of my new nonfiction book, too.

CF: You are doing a genealogy of meanness. Tell me about what you are taking on in that new project.

SS: It’s called Conflict is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair. It’s about three realms where I feel that conflict is misrepresented as abuse, through the overstatement of harm: the interpersonal realm, the criminalization of HIV, and Israel/ Palestine. I define conflict as “power struggle” and abuse as “power over.” My thesis is that when we deny our participation in creating conflict, and instead claim that we are victims of abuse, the power of the state is enhanced.

CF: Like calling the police instead of having a conversation with someone.

SS: Yes, and people get killed. So with the criminalization of HIV, for instance, these laws encourage people to call the police on someone who didn’t disclose their HIV status, regardless of their health, viral load, or whatever. For the past thirty years, the HIV negative person has been seen as being responsible for that status and for maintaining it; with criminalization, the HIV positive person becomes the “abuser,” while the negative person is now the person who has been criminally wronged. It is a state apparatus exploiting a new social trend of us not taking personal responsibility for our role in situations of conflict. Or, to give a different example, New York City has 200,000 cases of domestic violence, so when someone overreacts to conflict, claiming abuse when it is not abuse, they redirect resources away from those who most need them. The book’s final example is an analysis of the rhetoric surrounding the 2014 Israeli war on Gaza. Again, we see the exteriorizing of interior anxiety, negative group loyalty, the refusal to face one’s own role in creating conflict: all these elements that the book articulates converge on the murder of over 2,000 people in Gaza. I show that the same tropes an individual uses to claim “abuse” because they misunderstood or were made uncomfortable by an email, becomes the tools of government propaganda, that there is a direct relationship between the intimate refusal of accountability to the nationalistic projection. If we shun, cold-shoulder or bully the people we know because they say something or exhibit difference in a way that makes us uncomfortable, how are we going to be able to make peace or welcome refugees, or win justice? These two actions are antithetical.

CF: The final section of the book brings up your role as an outspoken critic of Israel. You’ve taken a lot of criticism and even had hatred and threats directed at you for being so vocal in your criticism of Israel.

SS: The truth is, I’m a tenured professor, so I haven’t had a lot of fear about my job security. Recently, though, I was falsely accused of anti-Semitism, and I did fear for my job when that happened. But I’ve never felt much at risk. Other people, particularly Arab professors like Steven Salaita at the University of Illinois, who lost his job because of his position on Palestine, are in far more jeopardy than I am.

CF: I suppose your work on conflict situates you to be quite willing to engage in strenuous debate around these controversial issues.

SS: I talk to people constantly whom I disagree with about Israel. I feel that it’s my responsibility to do that. The occupation is being carried out in my name on two grounds: because I’m Jewish and American. When I talk to really extremist people on this issue, it becomes immediately clear that they are grossly uninformed. Usually they have never had real experiences with Palestinians and have not listened to what they have to say about their own experiences. In the United States, this information is not passively acquired.

.

CF: I’m guessing this is another book that was hard for you to publish.

SS: Academic presses were concerned that because I don’t have advanced credentials, I would not be able to pass editorial review boards. I approach nonfiction as an artist. My books are not about “proof.” You don’t come out of a play and say, “That play was right!” You say, “that play revealed human contradictions.” My method is to offer a lot of ideas, and readers become interactive, in this way producing new knowledge. As far as commercial publishing goes, in the United States, Palestine cannot be used as an example for a larger argument. It is so stigmatized and under-discussed that it can only be its own subject. People are so ignorant, they have so little access to good information, that they don’t have the context to see how Palestine could be an example of something other than itself. The book wound up with Arsenal, a Canadian press, which seems fitting since HIV criminalization is happening in Canada. But will anyone in the U.S. pay attention to it? We will see.

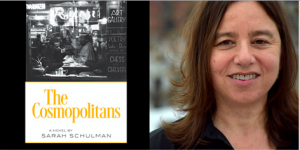

CF: Your other new book in 2016 is a novel, The Cosmopolitans, set in Greenwich Village in 1958. We follow a woman, Bette, who is fifty, from Ohio, and she has a kind of small life in New York. She has not had feminism to help her. Her best friend and neighbor is Earl, a black, gay actor, whose life is more dramatic than hers. The novel has an intelligence and a sincerity to it. It’s a lovely but disturbing book. We find out that the building where they live is the building on 10th Street where you spent some years growing up. That is a fascinating crossing between fiction and autobiography.

SS: This is all very layered, as is the book. It took me thirteen years to write; I started it when I was forty-four and finished it when I was fifty-seven. It’s a look back at my urban origins, but also it’s a portrait of pre-gentrification New York. I wanted to evoke the New York that was a refuge for people from uncomprehending backgrounds. The performance artist Penny Arcade has this joke about how we all left home and came to New York to get away from the most popular kids in school, and now, with gentrification, they’ve all moved to New York. It is the very people who couldn’t survive in their small towns who made New York a center for the production of ideas for the world, the very people who are getting squeezed out now. The novel shows neighbors and relationships, what apartment living produced; suburbanization privatized these human relations. The literary look back is to Balzac’s novel Cousin Bette, which, as I mentioned earlier, I studied at the University of Chicago in a class on nineteenth-century French realism. In Balzac’s novel, a spinster is betrayed by her family and wants to get revenge. So, she destroys everybody and everything, and in the end she wins. And, also, from the late 50’s, early 60ss is James Baldwin’s Another Country—black and white and gay and straight—on these same streets, but the women in the book are not real people. Balzac, Baldwin, and 1950’s kitchen sink realism are all called “real,” but how can that be so? The artist in me was intrigued

CF: These ideas coalesced for you over more than a decade, and they called back over your whole life.

SS: Yes, and then in 2003 a stage actress, Roberta Maxwell, asked me to me to write a play for her at the LaJolla Playhouse. Cousin Bette seemed like a great fit for that project. I decided to update it. It was in a program that included public readings and feedback, but the play, which was called “The Burning Deck,” a line from Elizabeth Bishop, was never actually performed. I worked with an actress named Diane Venora, who was the last woman to play Hamlet. In fact, in her career, she is the only actor in history to have played Ophelia, Gertrude, and Hamlet. Joe Papp directed her in Hamlet. I spent four weeks with her on this project. The actor Mark Lonnie Smith played Earl. So I saw these characters move around. But it was clear that it wasn’t going to get produced because the people in charge, the ones who run theaters, don’t understand these kinds of relationships of the powerless, where there are no white male protagonists, where it’s neither a “black” play nor a “white” one.

CF: So that’s maybe why the novel is structured as Act One, Intermission, and Act Two.

SS: Right, and act two is the revenge plot. A person has been transformed by having been falsely accused; she has a new tool, marketing, that provides her with power.

CF: Bette has Valerie, a first generation ad executive, as a female ally.

SS: Well, kind of, but to me, women who went into advertising in the 1950’s and 60’s are sort of like the women who became psychoanalysts fifty years earlier. New fields have room for women; old fields do not. But the irony of women in advertising is that they ended up making a lot of money and getting a lot of autonomy, but at the expense of women in general. Advertising is the enemy of women. The woman who came up with the campaigns “If I have one life to live, let me live it as a blonde” and “blondes have more fun” was a Jewish brunette contributing to white supremacy. So you get this kind of “power feminism” which came at a high cost for women, though not for individual women.

CF: In your novel, there is a lot of conflict. What fiction allows you to do is show it resolved or not resolved. You are essentially getting to work some of these issues out with these characters. Your nonfiction writing is helping you write your fiction, in that way. For me, you are an idea writer, a public intellectual, albeit for what is now a small public.

SS: I’m a subcultural public intellectual. I’m not on NPR, for example.

CF: I learned a lot from The Cosmopolitans—about community, about capitalism and advertising, about women’s lives, and about gay lives. It is a kind of social critique.

SS: Yes, Earl and Bette are out there on their own, without the benefit of feminism, the gay rights movement, or the Black Power movement. The idea of a community thinking out loud about their own condition has not yet occurred. They had to figure it out themselves.

CF: This novel couldn’t be set ten years later. It captures that “before” moment.

SS: It couldn’t be set even five years later. After the JFK assassination, everything started to shift quickly. Eisenhower is president in this book.

CF: So now I am thinking about today. The kind of community you depict in The Cosmopolitans will never happen again, not in the contemporary cities. So what do we have now? Facebook? You and I are Facebook friends, and you are quite active on it. Is that a new form of community making, community building in the 21st century?

SS: For me, personally, Facebook is very, very rich. I’ve gotten so much out of it on so many levels. The international information is extraordinary. In a matter of seconds, I can find things out from all over the world, and not from news media. So that’s amazing. But also, I’ve been able to put out ideas and get many, many responses. Conflict is Not Abuse is a book that I basically wrote using Facebook. I’d put out a thought and get so many suggestions and responses. It is humanizing, seeing people on vacation, or hearing their frustrations, whatever. A lot of people don’t use Facebook and can be self-righteous about that, but for me, it has helped me see other people, specific people, more multi-dimensionally, and they can see me that way too.

CF: I have to say I agree with you. I’ve posted, for example, about my father’s death and have been incredibly moved by the hundreds of responses. There’s humanity there.

SS: Yes, but you also have to practice restraint. The cruelty between the Hillary and Bernie people has been outrageous, but I don’t delete or block that stuff because it’s part of what I’m working on. The pro-Israel crazy people do horrible things to me—they alter my Wikipedia page, they post vicious things—but what I have realized is that if I just let them express their opinions and move on, nothing terrible happens. I’m not diminished in any way. Only when I get on their level do I get diminished. My phone number is listed. I know many writers of all levels of success who have unlisted their numbers, as if they think of themselves in a constant state of siege. But because I’m accessible, there’s no anxiety around me. Anyone who wants to talk to me can, so no one is desperate to talk to me. We can just communicate, we can reformulate a relationship.

Chris Freeman, a longtime contributor to The G&LR, teaches English and gender studies at USC.