THE ENCYCLOPEDIC Art and Queer Culture by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, published earlier this year by Phaidon Press, contains 250 artworks and a documents section that crisscross over more than a century and a quarter. The storyline is the emergence of same-sex relatedness as a definable identity. The artworks and documents chronicle this dramatic shift. The book has a global reach that challenges the conventional Western-centric, Caucasian view of GLBT people by including work from the developing world. Both editors are academicians. Lord is professor of studio art at UC–Irvine. Her books include The Summer of Her Baldness: A Cancer Improvisation (2004) and Son Colibri, Sa Calvitie: Miss Translation (2007). Meyer is professor of art history at Stanford and author of Outlaw Representation: Censorship and Homosexuality in Twentieth-Century American Art (2002).

More than a third of the book contains documents that contextualize the images—court testimonies, police and medical photographs, scrapbooks, fliers, book excerpts, essays, letters, and so on. Explains Meyer: “One of the reasons that the documents were so important was there are things that come out of activist movements, like manifestos, that are directly related to the visual images.” Adds Lord: “The images are about the context that anchors them—whether it’s high art or pop culture or pathologized representations of sexuality. The book has to do with a sort of phobic anxiety around the existence of sexual deviance, as well as an enormous pleasure in that existence.”

What defines the queerness of the artwork isn’t always the sexual orientation of either the artist or the subject but the empathetic rendering, the representation of the subject’s state of mind, or the confrontational implication of the image. Often, the artworks depict emblematic encounters between an artist and a subject, images and documents that reference the centrality of language. Included are several portraits of literary figures, such as James Baldwin, Gertrude Stein, and Oscar Wilde.

The artists and writers in Art and Queer Culture challenge cultural assumptions about gender and explore the nature of sexual non-normativity. Many propose a multiplicity of genders and consider gender as a social construction, fluctuating and mutable rather than permanent. Most of the images have signifiers and codes embedded into them, suggesting a schema of queer representation. Some are dress codes or accoutrements: leather and lace on males, monocles and tuxedos on females; corporal modifications, surgical or cosmetic; various genital signifiers. Others have to do with the physical body itself. As a primary site of personal identity and sexual orientation, the body is open to redefinition and politicization, especially in an age of gender re-assignment and reconstructive surgery. What a body is, is subject to modification. Let me focus on a few of the portraits in this book and offer a bit of back story for each.

Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1895.

Watercolor, private collection.

IN 1895, the night before one of three disreputable trials, Henri Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901) and Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) encountered each other once again, this time in London rather than in the Montmartre district of Paris, where they had met previously. Both were world-weary. Toulouse-Lautrec, an inveterate chronicler of the colorful and tawdry nightlife of the Belle Époque—music halls, circuses, brothels, and cabaret life—painted a body of work with explicit or veiled allusions to exhibitionism, voyeurism, prostitution, and same-sex affection. Some six years after this meeting, Toulouse-Lautrec died at 36 of complications from alcoholism and syphilis. Wilde, anticipating imprisonment at the time of the meeting, would be dead a mere five years later, age 46, in 1900. Both men knew despair and heartbreak. Toulouse-Lautrec maintained that “Love is when the desire to be desired takes you so badly that you feel you could die of it.” And Wilde lost the love that dare not speak its name along with public outing and humiliation. He was imprisoned for more than two years and spent two months in an infirmary after collapsing from illness and hunger.

The physical incongruence between the artist and subject couldn’t have been more striking. The artist was barely five feet tall with legs that had ceased growing and were conspicuously disproportionate to an average upper body, and he had difficulty walking even with the use of a cane. By contrast, Wilde was six-foot-three, a dandy who wore a black velvet coat and knee-breeches, silk stockings, lace cuffs and matching lace necktie, and patent leather shoes with silver buckles, and white gloves.

Toulouse-Lautrec had drawn Wilde several times before, but this night was different, because his subject was too distraught to sit for a portrait. Artist and subject were aficionados of absinthe and may have sipped some psychoactive concoction, and one might have observed them through lace curtains opposite each other seated on over-stuffed Victorian velvet settees. Toulouse-Lautrec mixed absinthe with cognac instead of water, dubbing the drink “earthquake.” Wilde hallucinated. He once imagined tulips spouting between cracks from the tile floor of a bar after he drank absinthe, reporting: “After the first glass, you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.” At any rate, this night—despite any mode of intoxication—Wilde obstinately refused the artist’s entreaty to sit for a portrait.

Disappointed, the thwarted Toulouse-Lautrec returned to his hotel room and painted from memory what was to become a well-known watercolor of his anxious and prematurely aging friend (Figure 1). Here Wilde is no longer the brazen dandy. Instead he is haggard, dissolute, dissipated; there are deep lines etched onto his furrowed broad brow; he is puffy-eyed from sleepless nights. Only his pursed, crimson lips are resolute. Drawn in three-quarter view, he gazes vacantly into the expanse of a doomed future. Toulouse-Lautrec added a background sketch of London’s Houses of Parliament, referencing the supreme power of the state. It was a prophetic touch: during one of the trials, Wilde was asked about the location of a male brothel, and he told the court it was near the House of Commons.

Toulouse-Lautrec’s empathetic portrait formulates a distinct and individual state of mind, but the painting also represents the predicament of the “homosexual,” at first medically pathologized, then institutionalized, criminalized, and incarcerated. Painted in Toulouse-Lautrec’s Japanese print-inflected watercolor style with shades of orange and yellow, the portrait stands apart from his other work because it is embedded in a historical context with an instantly recognizable storyline of oppression. It is inexorably anchored in time and place, and its symbolism has endured over several generations. The painting was lost for more than half a century until it resurfaced mysteriously in 2000 as an anonymous loan to the British Library for an exhibition to mark the centenary of Wilde’s death.

IN 1905, the contents of 24-year-old Pablo Picasso’s dimly lit studio in the Le Bateau-Lavoir building in Paris were a day bed, a long, unsteady table, two dilapidated chairs, and a tub. The artist’s subject, Gertrude Stein, rode a horse-drawn omnibus and climbed up a precipitously steep staircase to his studio in the Montmartre district. She agreed to sit for a portrait for the virtually unknown artist. It was the depth of a bitter winter, and a rusty, iron stove used for both cooking and heating was stoked continually for his famous subject’s comfort. Stein assumed her pose seated in a large broken armchair, and Picasso sat in a little kitchen chair. He painted very close to his canvas. On a small palette he mixed somber beiges, dark brown-grays, and different shades of sepia.

After ninety sittings, it was almost spring; the portrait was unfinished; and the sessions were about to end. Picasso was overwhelmed by Stein’s authoritative ego and formidable personality, and completing the portrait had become an insuperable challenge. Then, as Stein wrote in the Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, “All of a sudden one day Picasso painted out the whole head. I can’t see you any longer when I look, he said irritably. And so the picture was left like that.” He left for Spain’s Pyrenees and she for Fiesole, a town in the province of Florence.

Portrait of Gertrude Stein, 1906.

Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

For Pablo Picasso, 1906 was a pivotal year. His female bodies became monumental as he developed a new concept of the body, the so-called “nouvelle femme,” and increasingly his faces were mask-like and abstract. Upon Picasso’s return to Paris from Spain, having resolved any æsthetic conflicts about portraiture, he gave Stein the completed, no-longer-headless painting—having painted her face from memory—along with an Iberian mask that inspired the commanding face in the portrait (Figure 2).

Some complained that the portrait didn’t look like Stein, to which Picasso retorted: “Never mind, in the end she will manage to look just like it.” Of the portrait, Stein wrote in her monograph Picasso: “For me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me which is always I.” Stein was photographed under the portrait that hung in her atelier at 27, rue de Fleurus many times, most notably by Cecil Beaton. She donated the painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art upon her death in 1946.

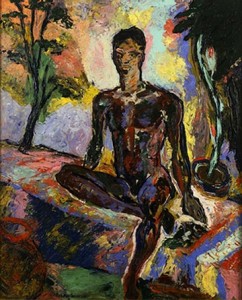

IN 1940, James Baldwin (1924-1987) visited the painter Beauford Delaney (1901–1979) at his New York studio at 181 Greene Street in Greenwich Village. Through the door, he heard Bessie Smith singing “Empress of the Blues,” preaching about lesbianism through song, through the blues. (“I know women that don’t like men. The way they do is a crying sin. It’s dirty but good, oh, yes, it’s dirty but good. There ain’t much difference, it’s just dirty but good.”) Baldwin knocked at the door. Delaney lifted the needle from the Victrola and opened the door. Baldwin had an eager half-smile on his face, and, in the words of Rachel Cohen in A Chance Meeting: Intertwined Lives of American Writers and Artists: “Delaney thought he was beautiful—narrow and quick, all desire and the hope of love.”

Baldwin wrote of their first meeting: “He had the most extraordinary eyes I’ve ever seen. When he completed his instant x-ray of my brain, lungs, liver, heart, bowels, and spinal column … [H]e smiled and said ‘come in,’ and opened the door. He opened the door all right.” David Leeming observed in his biography of Delaney, Amazing Grace, that the painter was experiencing “voices of despair” and was descending into disorientation. Delaney was in the throes of an identity crisis that included fears of being outed and subsequent ruin as an artist. A friendship between Baldwin and Delaney ensued from that afternoon encounter that was decisive for both. For the painter, it would lead to an acceptance of his sexual orientation for the first time.

During the 1950s and ’60s, Baldwin and Delaney joined the growing circle of African-American and other expatriates who sought refuge in Paris. Over the next thirty years, Delaney portrayed Baldwin in at least ten drawings and paintings (Figure 3), and the latter believed that the artist was his “principal witness.” Baldwin said of his lifelong friend: “Beauford’s work leads the inner and the outer eye, directly and inexorably, to a new confrontation with reality.”

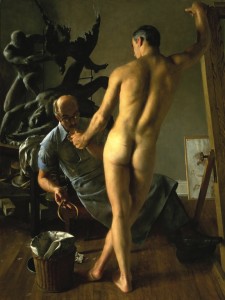

JOHN KOCH (1909-1978) had a very successful career painting commissioned portraits of prominent New Yorkers. He lived with his wife of 43 years, Dora Zaslavsky, a piano teacher at the Manhattan School of Music, in a fourteen-room apartment with massive windows, spectacular views, antique furniture, and paintings of the El Dorado, an iconic twin-spired Art Deco building overlooking New York’s Central Park. The painter liked to wear elegant velvet suits, using the apartment as a theatrical backdrop where his models, like actors, played roles.

It was a self-contained biosphere with interiors as rich as Koch’s inner emotional life—subjects who may never have met sketched and painted together in scenes that never happened. One of his subjects was Ernest Ulmer (1921-2012), part of a circle of friends and a piano student of Dora’s. Ulmer was dazzled by the logic and intricacies of the contrapuntal and studied Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier in minute detail. And Koch was unambiguously dazzled by Ulmer, painting him quite a few times. In The Sculptor (Figure 4), he painted a nude of Ulmer with detailed musculature and in-your-face buttocks angled toward the viewer. The dramatic painting—an entr’acte, with the artist and model on a break—depicts an intimate, erotically-charged interlude, complex and suggestive, an unequivocal example of male desire with encrypted, fetishized objects: a posing strap, a pair of calipers (used to measure what?). Koch averts his gaze from Ulmer, avoiding direct eye contact. The model steadies the artist’s hand as he delicately lights a cigarette.

The Sculptor is perhaps the most revelatory of Koch’s paintings, a compelling illustration of an artist at odds with himself, holding a contradictory definition of his own sexual orientation. The painting is a study in complexities of counterpoint. Ulmer was the subject of several paintings; one hung in his living room for many years and was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007.

(Homage to Benglis), 2011. Color photograph.

HEATHER CASSILS, a Canadian artist, and Robin Black, a body-builder and photographer, collaborated on LadyFace/ ManBody, an e-zine devoted to pinups that signify an ever-changing cultural landscape. Black took four photographs each day documenting Cassils’ transformation into hyper-muscularity and masculinity (Figure 5). Cassils gained 23 pounds in 23 weeks, writing: “I did this by adhering to a strict bodybuilding regime. … I consumed the caloric intake of a 190-pound male athlete. I also took mild steroids for eight weeks of the training,” and used an “exaggerated physique to intervene and interrogate systems of power and control.” Enthuses co-author Catherine Lord:

That work is exclusively and beautifully interesting. Such a mind-fuck or body-fuck whatever way you want to say it. Heather Cassils’ image of the torso with the red lips above it is really incredible. It’s really difficult to tell in what way she achieved a male body. She worked out. She gained 23 pounds of sheer muscle by eating some special diet and working out like a crazy person for eight hours a day. She had a double-mastectomy. It’s really a confounding and extraordinary image. I was just blown away by it.

When Michel Foucault proposed, “But couldn’t everyone’s life become a work of art? Why should the lamp or the house be an art object, but not our life?” he echoed Wilde’s often-quoted, but not always understood, line: “One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art.” Judith (aka Jack) Halberstam, author and theorist, defines “the queer ‘way of life’ as subcultural practices, alternative methods of alliance, forms of transgender embodiment, and those forms of representation dedicated to capturing these willfully eccentric modes of being.” If there’s a central thesis to Art & Queer Culture, it is that a queer way of life requires creativity, activism, and opposition to power domination and to oppressive gender roles. The close encounters of the queer kind in this book, the artworks and documents, each with a specific history and compelling back story, could be the substance for a narrative work, whether a play, a novel, or a film.

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, writer, and photographer for more than fifty years.