THE THIRTIETH ANNIVERSARY of the AIDS epidemic was commemorated last year in two issues of this magazine, which covered the crisis from a range of perspectives—political activism, cultural expressions, scientific developments—but there was no mention of the various AIDS memorials that have emerged and evolved over the years. In fact, there are quite a few such memorials throughout the United States. For the most part, their significance is confined to their immediate city or locale, which is to say that a national memorial has yet to be conceived.

The argument for a national memorial derives from the immensity and duration of the epidemic in the U.S. and worldwide. As of 2008, the latest year for which statistics are available, 617,025 people had died of AIDS in the U.S. Despite dramatic breakthroughs in HIV treatment starting in the late 1990’s, well over 15,000 Americans continue to die of the disease each year.

While HIV is clearly a national—indeed a worldwide—epidemic, its impact has been felt more strongly in some areas than in others. Especially among gay men, death rates have been highest in cities like New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles, which have a disproportionate concentration of gay residents. In general, these tend to be the cities in which AIDS memorials have been constructed. What follows is a partial chronology of AIDS memorials in the U.S.

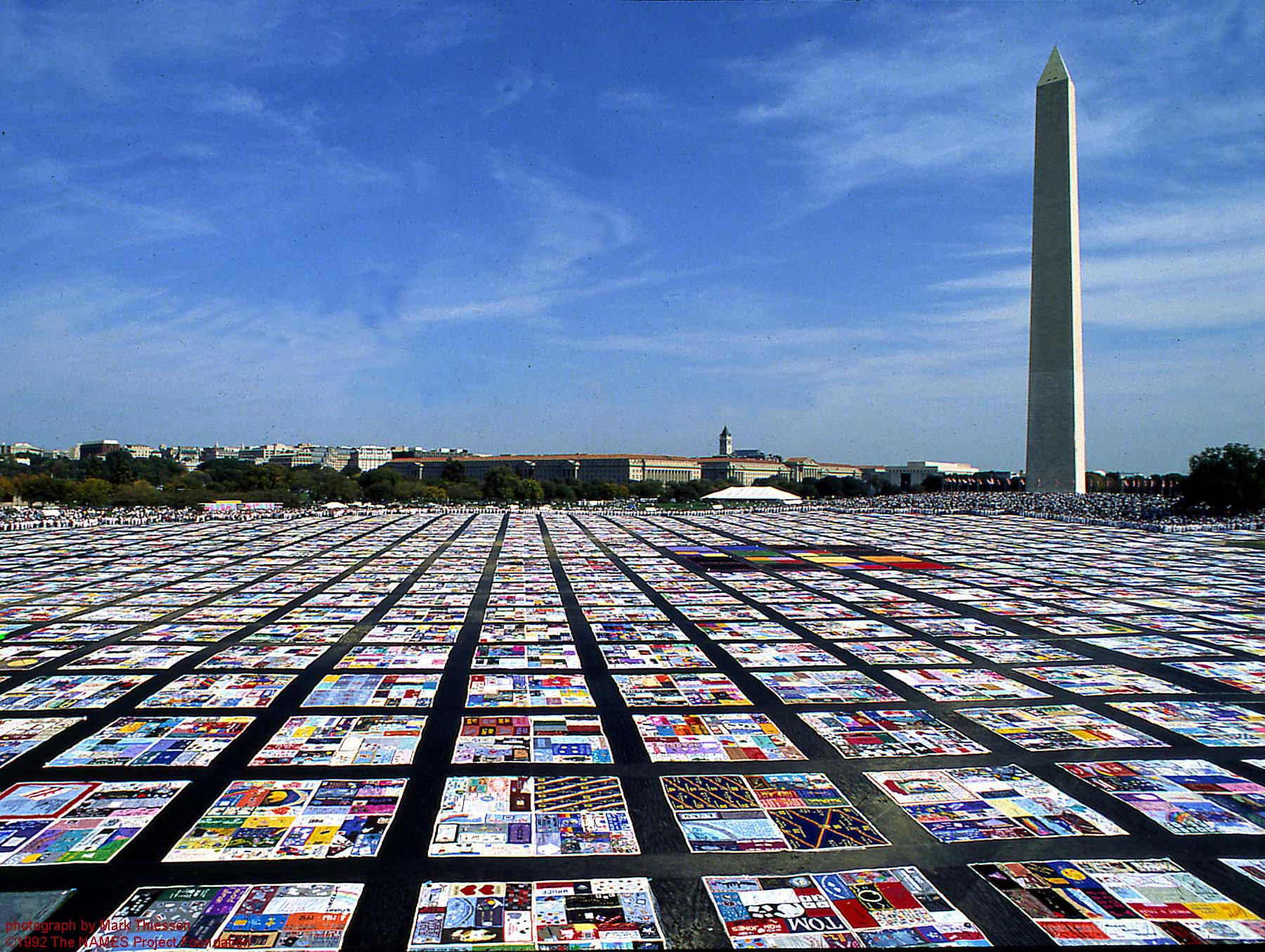

The AIDS Memorial Quilt (1987)

The Quilt is undoubtedly the best-known memorial, albeit a traveling one, and it continues to be used throughout the country as an HIV prevention and educational tool. It was first displayed in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 11, 1987, when it consisted of a mere forty panels. Since then, it has exploded to 44,000-plus panels with an estimated weight of 54 tons. As of 1992, it included panels from every U.S. state and 28 countries

The Quilt is undoubtedly the best-known memorial, albeit a traveling one, and it continues to be used throughout the country as an HIV prevention and educational tool. It was first displayed in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 11, 1987, when it consisted of a mere forty panels. Since then, it has exploded to 44,000-plus panels with an estimated weight of 54 tons. As of 1992, it included panels from every U.S. state and 28 countries

The idea for the Quilt came to its founder, Cleve Jones, at a 1985 candlelight march to honor the memory of San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone, who were murdered by Dan White in 1978. While planning the demonstration, Jones learned that more than 1,000 San Franciscans had been lost to AIDS, and he asked the marchers to write the names of these friends and loved ones on placards and carry them in the march. When it was over, Jones and other participants taped the placards to the walls of the San Francisco Federal Building. This wall of names resembled a patchwork quilt, and thus was born the idea for the AIDS Memorial Quilt.

The AIDS Memorial Grove, San Francisco (1991)

The Grove is a seven-acre area in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park that began in 1991 when Mayor Art Agnos planted a redwood tree in memory of the first San Franciscan lost to AIDS ten years earlier. Carved out of a brambly area of the park, the Grove expanded slowly through the efforts of the numerous volunteers who help on a monthly basis with its clearing and upkeep. In 1996, the U.S. Congress designated the AIDS Memorial Grove as an official national memorial, thanks to legislation initiated by Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi and Senator Dianne Feinstein.

The Grove is a seven-acre area in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park that began in 1991 when Mayor Art Agnos planted a redwood tree in memory of the first San Franciscan lost to AIDS ten years earlier. Carved out of a brambly area of the park, the Grove expanded slowly through the efforts of the numerous volunteers who help on a monthly basis with its clearing and upkeep. In 1996, the U.S. Congress designated the AIDS Memorial Grove as an official national memorial, thanks to legislation initiated by Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi and Senator Dianne Feinstein.

A PBS documentary (The Grove) that aired last fall focused on a controversy that erupted after the memorial became a national landmark. Desiring to elevate the Grove’s national visibility, the board of directors launched an international competition for the design of a memorial structure to be built on the site. The winning design called for the placement of a forest of black steel poles meant to resemble trees incinerated in a forest fire. These skeletal “trunks” would symbolize the destruction of lives from the AIDS epidemic, while placing them amid living trees would convey a sense of hope by contrasting them with the growth of new foliage.

Controversy erupted over the winning design and its attempt to symbolize “death” in a way that many people found distasteful. Soon people began to question the need for any artificial structure, which would necessarily entail the invasion of foreign objects and materials into what had been a natural space, a sanctuary of plants and trees whose serenity people found healing and inspirational. In the end, the board decided by a vote of eight to seven not to implement the winning design but rather to preserve the natural space without any abstract, anomalous structure or object.

Las Memorias, Los Angeles (1993)

The AIDS Memorial Wall, as it is also known, is “dedicated to promoting wellness and preventing illness among Latino populations affected by hiv/aids.” Lincoln Park was selected as the site for Las Memorias because of its rich cultural and artistic history with the Latino community, and for its proximity to the Rand Schrader AIDS Clinic.

The AIDS Memorial Wall, as it is also known, is “dedicated to promoting wellness and preventing illness among Latino populations affected by hiv/aids.” Lincoln Park was selected as the site for Las Memorias because of its rich cultural and artistic history with the Latino community, and for its proximity to the Rand Schrader AIDS Clinic.

The monument consists of eight wall panels, six murals depicting life with AIDS in the Latino community, two granite panels that contain the names of individuals (currently 350) who have died from AIDS, and an archway set in a garden intended to represent a Quetzalcoatl serpent—a Mesoamerican deity. According to associate director Eddie Martinez, Quetzalcoatl symbolizes rebirth based upon a legend in which his body is consumed by fire and transformed into a greater energy. The shape of the serpent in Lincoln Park is formed by the entire monument and can only be discerned from the sky. The arch (shown in the picture) is the serpent’s tail, and the panels become the serpent’s feathers or scales.

The Key West AIDS Memorial (1997)

The Key West AIDS Memorial consists of a series of granite slabs that form a walkway approaching the White Street Pier. Over a thousand names are inscribed on the pavement (and can also be seen on a website at keywestaids.org).

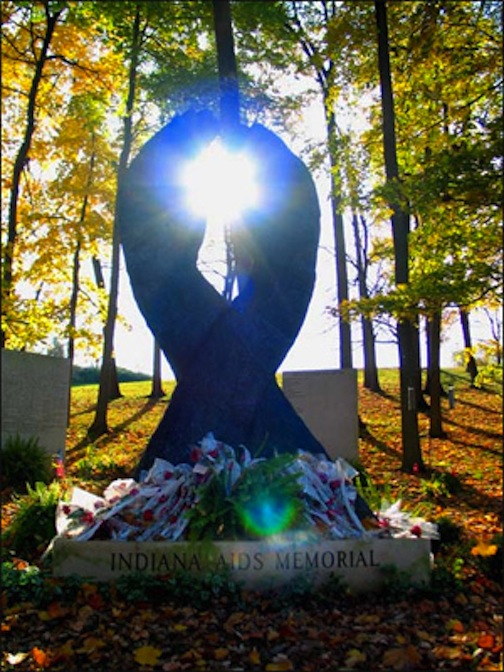

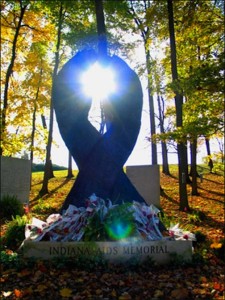

AIDS Memorial (Crown Hill, IN, 2000)

Situated at Crown Hill in a beautiful wooded area of a cemetery, this memorial is surrounded by historic headstones and other artifacts that date back to the late 1800’s. A series of limestone tablets, each inscribed with the names of people who have died from AIDS, form a semicircle around the memorial. As of October 2003, a tablet has been displayed for “Friends, Family and Those Who Care.

Situated at Crown Hill in a beautiful wooded area of a cemetery, this memorial is surrounded by historic headstones and other artifacts that date back to the late 1800’s. A series of limestone tablets, each inscribed with the names of people who have died from AIDS, form a semicircle around the memorial. As of October 2003, a tablet has been displayed for “Friends, Family and Those Who Care.

AIDS Memorial Chapel (Albuquerque, NM, 2000)

Housed at the Center for Action and Contemplation in a building that was formerly home to the Damien Brothers Community, whose ministry was with the hiv/aids community, this memorial consists of an etched glass window dedicated to those lost to the epidemic.

Housed at the Center for Action and Contemplation in a building that was formerly home to the Damien Brothers Community, whose ministry was with the hiv/aids community, this memorial consists of an etched glass window dedicated to those lost to the epidemic.

AIDS Memorial Park (New Orleans, 2008)

The memorial is comprised of a configuration of bronze circles, each framing a glass disc with the face of an individual. Some of those pictured are people with AIDS; others are activists who have fought against hiv/aids in the region. Leading up to the memorial is a pathway of granite stones inscribed with names of those lost to AIDS.

The memorial is comprised of a configuration of bronze circles, each framing a glass disc with the face of an individual. Some of those pictured are people with AIDS; others are activists who have fought against hiv/aids in the region. Leading up to the memorial is a pathway of granite stones inscribed with names of those lost to AIDS.

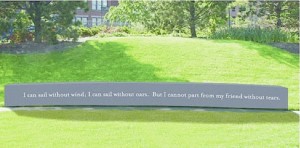

Hudson River Park (Greenwich Village, NYC, 2008)

New York City, in many ways the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S., had no memorial in place prior to Hudson River Park, which was dedicated 2008. Situated in a beautifully landscaped knoll at former Pier 49 between West 11th and 12th Streets, a horizontal slab bears the following quotation: “I can sail without wind, I can row without oars, but I cannot part from my friend without tears.”

New York City, in many ways the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S., had no memorial in place prior to Hudson River Park, which was dedicated 2008. Situated in a beautifully landscaped knoll at former Pier 49 between West 11th and 12th Streets, a horizontal slab bears the following quotation: “I can sail without wind, I can row without oars, but I cannot part from my friend without tears.”

The Infinite Forest (Greenwich Village, NYC, 2013)

This memorial will be located in Greenwich Village adjacent to the former St. Vincent’s Hospital at what was once known as St. Vincent’s Triangle Park. The winning design, “Infinite Forest,” which was selected this past February, is simple in concept, with groves of birch trees, adjacent seating areas, and mirrors on three sides that add a modern urban element.  The design was described as “a pastoral and modern oasis that provides tranquility and an opportunity for reflection amidst the city’s noise.” As visitors stand amid trees surrounded by mirrors that reflect each other, they will witness images repeated multiple times, offering a sense of the infinite that may bring different associations for each person.

The design was described as “a pastoral and modern oasis that provides tranquility and an opportunity for reflection amidst the city’s noise.” As visitors stand amid trees surrounded by mirrors that reflect each other, they will witness images repeated multiple times, offering a sense of the infinite that may bring different associations for each person.

The events surrounding the conceptualization of “Infinite Forest” echo somewhat those of the Grove in San Francisco. Both projects included individuals with deep personal connections to the cause; both involved debate over location, place, and design; and both invoked questions of whether the memorial should preserve local memories and associations or aspire to national significance. Indeed, both contemplated the central question with which I began my research: is there a need for a national AIDS memorial?

MEMORIALS in general serve a number of purposes in addition to honoring and preserving the memory of those who have died: educating visitors about the crisis and its history; transmitting this history to future generations so they’ll understand its impact on their own lives; providing a solemn space where people can contemplate the meaning of the loss and its lessons for the future. In the case of the AIDS memorials, perhaps because the crisis is ongoing, the goal of providing a sanctuary for those personally affected by the epidemic is of paramount importance. Also striking is how many memorials included “social change” as part of their mission: a desire to raise people’s consciousness about the severity of the ongoing crisis and the need to redouble our efforts at prevention and cure.

The AIDS Quilt, the most venerable memorial of them all, has always stressed the goal of social change—and has undoubtedly made good on this mission. In 1987, when the first panel of the Quilt was sewn, public officials were debating mandatory testing and quarantines of infected citizens. Homophobic reaction to hiv/aids was rampant. But today, thanks in part to the attention the Quilt brought to the humanity of those who had died, AIDS prevention and treatment are a major component of state and federal public health initiatives.

In the end, all of these undertakings may prove unequal to the enormity of the loss from the AIDS pandemic. Perhaps the best way to commemorate both the horrors and the heroism of the HIV era will be through the establishment of a permanent museum comparable to the Holocaust Museum in Washington. At present, there are a number of small art museums dedicated to presenting the artwork of people living with AIDS. One is the AIDS Museum in Newark, New Jersey, which is focused exclusively on educating students in New Jersey and New York City, and which hopes to secure the funding needed to secure a permanent location. But, of course, we have yet to reach a national consensus on the importance of the epidemic or even the legitimacy of formally honoring its victims. For now, at least, efforts to preserve the memory of those lost is likely to remain a local undertaking.

Stephen Hemrick is the manager of business development and advertising for this magazine.