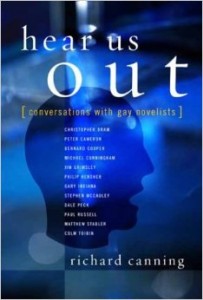

Hear Us Out: Conversations with Gay Novelists

Hear Us Out: Conversations with Gay Novelists

by Richard Canning

Columbia University Press.

358 pages, $62.50 ($24.95, paper)

IN THIS, his second book in a proposed three-volume series, literary interviewer Richard Canning offers up more of the meaty, critically rich interviews of the kind that he gave readers in his first book, Gay Fiction Speaks (which I reviewed in the Fall 2001 issue of this journal). The twelve writers in Hear Us Out are an impressive bunch, including such well-known gay novelists as Christopher Bram, Michael Cunningham, Bernard Cooper, Stephen McCauley, Gary Indiana, and Colm Tóibín.

The interviews constitute what Canning, a professor in England, calls “the next chapter,” a group of writers whose work was “enabled” by the first volume’s writers (which included Edmund White, Andrew Holleran, Allan Gurganus, and Dennis Cooper). The new interviews do indeed provide considerable insight into how the “enablers” influenced the next generation’s development, and they delve into the question of influence more generally. Henry James, Marcel Proust, Virginia Woolf, and Vladimir Nabokov are the names that come up the most persistently as mentors.

As an interviewer, Canning makes a point of querying all of his subjects about a number of topics, such as whether there’s a “gay æsthetic” or “sensibility,” and, if so, what it consists of. Brit Hensher describes the gay æsthetic as “a great big jumble sale to which we all bring something new.” Peter Cameron asserts he doesn’t know what such an æsthetic is, but that perhaps a better distinction to make is between the masculine (external) and feminine (interior) sensibilities. Indiana declares that today “there’s no secrecy—and no sensibility either.”

Canning comes to the interviews with his own quirkier preoccupations, such as “closed” versus “open” narratives, which everyone is asked about. In this formulation, his questions come off as unnecessarily academic. There are a few moments, perhaps inevitably, when it seems Canning is trying to impress his subjects rather than connect with them. He’s also fascinated with writing that depicts sex. This tends to juice up the interviews, but also proves to be a worthy line of inquiry, eliciting this from Michael Cunningham: “We have great examples of how to get characters through a dinner party, but almost nothing on how to get through a good fuck.” Cooper recalls a friend observing, “writing about sex-that’s-just-sex is like writing about chewing instead of about tasting food.”

Paul Russell makes some of the boldest comments (along with Indiana) in the book, among them: “In a sense, only mediocre gay novels can be gay novels.” Truly great gay novels, he adds, “do unconventional work [by]thwarting expectations.” Pages earlier, Russell suggested gay literature acts as a “self-fulfilling prophecy.” That is, “We tell stories to make them possible.” Some of the authors also explore how being gay has affected their writing. Cooper talks about “never taking anything on face value when I was growing up,” living in a world “charged with innuendo.” He also says being gay influenced his interest in “what’s true and what’s myth.”

The interviewees also discuss their writing lives and offer a few insights into the process and craft of fiction. For example, Cunningham describes the advantages of writing in the first person, and McCauley says a plot for him “has to have roots in the past and consequences for the future.” In several places Canning shepherds the conversation to how the AIDS epidemic has affected narrative structure and substance over the years. For example, he and McCauley discuss the demands AIDS as a subject places on the emotional center of a work.

Readers of Hear Us Out should be prepared to lengthen significantly their gay fiction reading list. The interviews also get those creative juices flowing, so readers should block out some time to fret over that great American novel they’ve always wanted to write.