Compared to What? The Improbable

Compared to What? The Improbable

Journey of Barney Frank

Directed by Sheila Canavan and Michael Chandler

Pack Creek Productions

The title of this documentary refers to former Congressman Barney Frank’s standard rejoinder when answering those who complain that GLBT equality isn’t happening fast enough. Sure, “Don’t ask, don’t tell” wasn’t a perfect solution in 1993, but compared to what? By his own admission, Frank lives and breathes policy and politics around the clock, but the film sets out to explore his private life and figure out what makes him go. We meet his husband, Jim Ready, and get to watch them doing some interior decorating, but much of the footage documents backstage moments in Frank’s public life: getting ready for a TV interview, regaling guests at a reception, answering questions at a town meeting. The film reminds us how Frank came out under duress when a scandal erupted in 1985—it seems a gay employee was hustling out of his D.C. apartment—and how he saved his career by admitting to Congress that he was gay (though not a purveyor of gay prostitution). A strike in his favor may have been that Frank doesn’t seem very “gay” according to most stereotypes, a fact by which he is bemused. He has no fashion sense, forgets to tuck in his shirt, and would never be accused of having a “camp” sensibility. Which is not to say that he lacks a sense of humor: it is one of his trademarks. He quips that he used to be admired as a Congressmen but hated for being gay, while now he’s accepted as gay but dissed as a former Congressman. It was in the latter role, of course, that he became famous and powerful: a working-class Jewish kid from Hudson County, New Jersey, who didn’t let being gay stand in his way.

Wendy Fenwick

Rebel Heart

Rebel Heart

Madonna

Interscope Records

Once demeaned as the Queen of the Obscene, Madonna is now asking important questions about ageism and the expiration date we place on a woman’s sexuality. No longer a girl, the Material Mama bared her breasts in Interview, flashed her G-string at the Grammys, and planted a sloppy kiss on a much younger man, the rapper Drake, onstage at Coachella. True to form, she’s not apologizing for it. As the defiant diva told Rolling Stone, “This is what a 56-year-old ass looks like.” Her thirteenth studio album, Rebel Heart, renews Madonna’s reputation as a cultural lightning rod, and it’s her best work since 2005’s “Confessions on a Dance Floor” as it careens from the candid to the confectionary. “Wash All Over Me” is a moving ballad on death and the dissolution of the ego, something which, in “Joan of Arc,” is not as “steely” as one might think. The dance tracks are sheer missile strikes, from “Living For Love” to “Bitch I’m Madonna” (featuring Niki Minaj). The album’s low points, “Holy Water” and “S.E.X.,” are more embarrassing than erotic even if they reveal a fetish for the dental chair. Much fresher are “Veni Vidi Vici,” which finds Madonna posing as a female Caesar and boasting, “When I struck a pose, all the gay boys lost their minds,” and “Unapologetic Bitch,” with its reggae rhythm and air horn (compliments of Diplo). Madonna recently told Cosmopolitan: “People don’t think I have the right to continue to be successful, to be sexual, to have fun,” which is “sexism and discrimination.” She’s probably right. Given that Americans are living longer and longer, pop music’s reigning rebel may be reinventing herself once more as the Venus of the Viagra generation.

Colin Carman

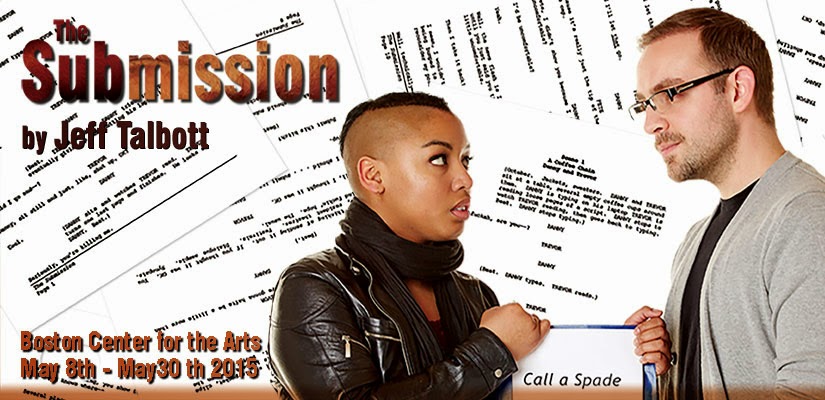

The Submission

The Submission

A play by Jeff Talbott

Zeitgeist Stage Company

Boston, May 5-30

Danny is a gay white dude who has written a play about inner-city African-Americans called “Call a Spade.” It’s a soul-searching drama that wouldn’t stand a chance if signed by a white male writer, so he submits it for production under a black-sounding female name. When it’s accepted by a prestigious company, Danny needs someone to play the playwright, so he hires a struggling black actress named Emilie. What could go wrong? Right from the start, Emilie begins to discover that Danny’s fascination with the ghetto belies a kind of cynical acceptance of racial consciousness, if not outright racism, as a fact of life. For example, he casually assumes that there are “Blony” and “Bloscar” awards—secondary categories of Tonys and Oscars set aside for African-Americans—and that some black people are “Oreos.” Oh, grow up! That Danny is gay adds an interesting complication, giving him a minority status that allows him, he contends, to understand the plight of black Americans—a claim that Emilie hotly rejects. Being gay also bolsters Danny’s bona fides as a victim and a liberal—he can’t really be racist, can he?—so both his lover and his best friend tend to give him a pass. What’s more, Danny will even concede that there are “gay” set-asides and other tokens of inclusion with which society conceals its underlying homophobia. Still, when Danny finally utters the “N” word during a heated argument, it comes as a shock—stopping the action for several toe-curling minutes—precisely because that most taboo of words had been so studiously avoided up to this point, however much it was lurking under the surface all along.

Richard Schneider Jr.