THE CAMPUS OF GLIMMERGLASS OPERA Festival rolls up the mountain shore near the north end of a strayed-east Finger Lake named Otsego, ten miles north of Cooperstown’s Baseball Hall of Fame and sixty miles west of the malfunctions of Albany. For the months of July and August these bucolic acres leap to life as one of America’s major opera sites, offering four productions plus dozens of recitals and lectures.

Virtually from its inception in the late 1970s, a feature of this festival has been its handsome eight-and-a-half-inch-square program booklet listing the cast and credits for each production, plus background essays on the chosen operas. Attending each season, I have accumulated a foot-long shelf of these publications. The covers of recent editions have featured a color reproduction by a different American painter each season. Since every Glimmerglass patron is provided with a program for each performance, this adds up to a major print run and broad dissemination of that year’s art selection.

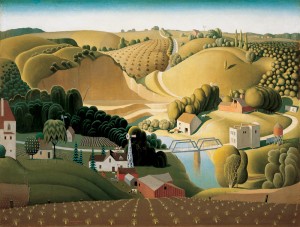

The cover art for the 2012 season was Grant Wood’s Stone City, Iowa—one of those charmingly stylized landscapes of his that have had such broad influence on children’s book illustration and fantasy film design. “Friends of Dorothy” will recognize that Judy danced down a yellow brick road like the one that unspools across Grant Wood’s landscapes. I’ve always been partial to Stone City without questioning why; it lacks the folk-art punch of Wood’s similarly presented scene of Paul Revere’s ride. But it has always exerted a special

Estate of Grant Wood, New York, NY.

appeal, and suddenly witnessing an opera house full of its reproductions, I realized why: the artist has wittily and boldly tucked in an unexpected depiction of the glans penis.

Once you spot it, it’s impossible not to see: Wood gives this impressive glans pride of place as the central hillock and bathes it in his warmest sunlight. He dangles a country lane down from his horizon to accent the lip of its flange. He even risks a non-topographical ravine to provide a urethra. The only concession he makes to plausible deniability is to fudge the object’s right contour, along the forest edge, and to plant a couple of trees on its sleek surface. This was obviously sufficient camouflage for his local audience—but then the grimly repressed ladies in Wood’s portraits (see below) may never have seen a penis in the flesh.

I’m surprised not to have seen it before, as I’ve always considered the glans one of Nature’s exquisite designs—whether as the perky slit-tip cap of the flaccid penis or as the proud warrior’s helmet of a full erection. And now to have it celebrated so openly—in the hand of thousands of opera buffs! It was as titillating as being in a shopping mall where dozens of those Abercrombie & Fitch bags adorned with luscious physique photos are displayed by shoppers innocent of their effect on one’s libido.

But the more pressing question concerning Stone City is why the painter chose to include that hillock cum cock tip in the first place. Although often labeled an American Primitive, Grant Wood was no Grandma Moses, earnestly celebrating the simple country life and family values. He traveled abroad to study art in Paris and Munich. He eventually married—in his mid-fifties—but divorced his wife just four years later.

His portraits of fellow Iowans are sardonic and unsentimental. Two of the most iconic paintings in all of American portraiture are his American Gothic, which was painted in the same year (1930) as Stone City, and the overtly satirical Daughters of Revolution (1932). It’s easy to imagine this artist harboring wicked impulses as he painted these prim-lipped, judgmental neighbors, taking secret pleasure in twitting their vanity—or in hiding an erotic hillock in their landscape.

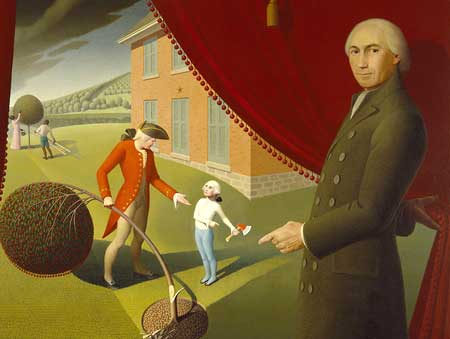

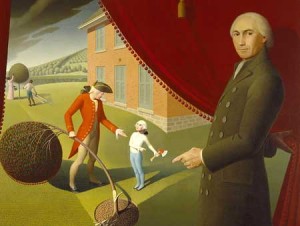

Thus Wood was hardly the dour, irony-challenged painter of American Gothic fame. On the contrary, he was given to both satire and whimsy in his art. The latter is apparent in his many landscapes in the style of Stone City, even without the trick of the eye. An element of satire suffuses his work, and it is of the devilishly wicked variety such that there’s always a non-satirical interpretation. What may be his second-most famous painting, Parson Weems’ Fable (1939), could be a straightforward portrayal of a favorite American legend, the one about a young George Washington confessing to his father that he felled the cherry tree, a legend that was later invented by one Parson Weems, who seems here to be witnessing the event from a weirdly close-up vantage point. And then you notice that the tree is but a twig, George’s head is that of the Gilbert Stuart portrait, and the fringe around the window is made of cherries (see page 12).

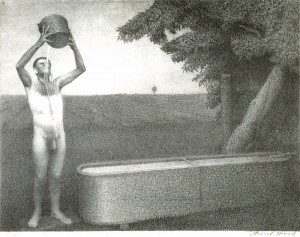

A recent biography of Wood, Grant Wood: A Life, by R. Tripp Evans (Knopf, 2010)—reviewed by Cassandra Langer in these pages (Jan.-Feb. 2011)—finally lifts the veil on Wood’s sexuality, which was far more complicated than his homespun popular image would suggest. Evans shows how Wood struggled with his sense of manhood his whole life, never feeling that he measured up, and argues that beneath this struggle were the desires of a closeted gay man. Only rarely did he allow these homosexual urges to find their way into his work, though they did so on occasion, notably in the 1939 lithograph Sultry Night, which shows a nude man bathing in the out-of-doors, pouring a bucket of water over his head.

In short, Wood was quite capable of creating the visual double entendre that we find in Stone City. The fact that he was undoubtedly a gay man, however deeply closeted, could provide a motive for this private joke—which seems to have had exactly the effect he might have been hoping for: wide distribution of his painting at a respectable cultural event whose patrons would be staring down a male urethra without even knowing it.

(Ah, what they missed! The most irrefutable argument for circumcision lies in the realm of æsthetics: a foreskin seems a mistake of Nature, a wrinkled cowl that obscures one of the most elegant design details of male anatomy, reducing the penis to a lumpen salami. So, all hail Grant Wood for crowning Stone City with that splendid hillock!)

A SUBSIDIARY question concerns the choice of this Wood piece for the cover of

Glimmerglass’ 2012 season. The quick answer is that one of that summer’s productions was Meredith Willson’s The Music Man, and the set designer had adapted Stone City as a backdrop for Willson’s River City scene. With the cover art thus a shoo-in, maybe no one would notice that there was “something extra” in Wood’s design. But how aware, if at all, were the producers of Glimmerglass of the painting’s little secret?

Francesca Zambello has been general director since 2010, and it was she who introduced Broadway musicals into the program mix. She’s known to be a very hands-on executive who concerns herself with all of the festival’s artistic details. She personally introduces each performance. During the 2013 season, when my husband and I drove onto the grounds to pick up a weekend parking permit, who should greet us but Ms. Zambello herself? “Hi, guys,” she called as we left our car. “Here for the recital?” We fanned out our mail-ordered tickets for the long weekend’s four productions but confessed we knew nothing about the imminent recital. “In the pavilion behind you,” she told us. “Tickets are still available.” We half expected her to tear off a couple from a big roll she carried. (Of course we went to the recital.)

That’s typical of Zambello’s intimate involvement. So, perhaps she was aware of the Stone City hillock. Professionally, she has never shied away from the homoerotic in operas that she has directed—including Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride at Glimmerglass in 1997. Let me quote from an appreciation of baritone Nathan Gunn by New York Times music critic Anthony Tommasini in the Sunday Arts section on January 8, 2006. After warning the reader not to expect Mr. Gunn to repeat certain Verdi roles, Tommasini refers to the time that the tenor gave

an arresting performance as Oreste in Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, a role he sang to acclaim at the Glimmerglass Opera in 1997. Directed by Ms. Zambello, that production presented Oreste and his friend Pylade (William Burden) as intensely bonded (and presumably romantic) Greek companions, who had been imprisoned by the enemy Scythians. Both artists gave courageous performances and made pitiably beautiful figures onstage as they were beaten, chained together and stripped to loincloths.

I vividly remember the scene that Tommasini describes. Both Nathan Gunn and tenor William Burden were at their peak physically as well as vocally; and the libretto demands a passionate exchange between Oreste and Pylade, as both assume they are facing execution. Each in turn declares his love and insists that he be allowed to die first since, literally, “I could not endure witnessing your death” (the dialogue emblazoned across the top of the proscenium in supertitles). This was easily the most homoerotic scene I’ve ever experienced in opera. Later, in a Metropolitan Opera production of An American Tragedy, director Zambello would again strip the hunky Gunn to the waist. (Gunn has also memorably sung Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd.)

Whether Zambello or anyone else at Glimmerglass suspected anything unusual about the Wood painting is impossible to determine. I’d like to think that we live in an age when they knew perfectly well what was going on but decided to go ahead with it anyway.

Alfred Lees worked in the publishing business for 35 years, finishing up as managing editor of Popular Science before retiring. He lives in New York City.