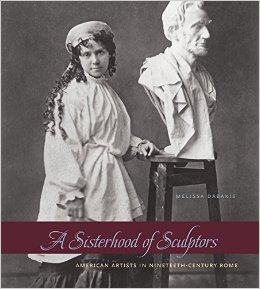

A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome

A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome

by Melissa Dabakis

Penn State. 286 pages, $29.95

AS I WRITE, a media circus is spinning around Harper Lee’s new old book, Go Set a Watchman, which has set off a feeding frenzy in the publishing industry. No such fanfare has greeted Melissa Dabakis’ new book, A Sisterhood of Sculptors: American Artists in Nineteenth-Century Rome, though her material is equally inflammatory in the realm of race relations. It addresses the root causes that Lee famously explored in her renowned novel To Kill A Mocking Bird, the book that still sits on my bookshelf and that helped me to form my understanding of racism as a teenager.

It’s important to remember that in the mid-19th century, before art became a part of the investment banking business, a group of exceptionally creative women escaped the bonds of matrimony in cosmopolitan Rome, where they sought individual freedom, the pursuit of justice, and professional achievement. They formed a close-knit and supportive community mentored by the lesbian thespian Charlotte Cushman, who appropriated masculine sartorial dress as a code for female independence. In Rome, these women created a society made up of lesbians and sexually fluid females. Some were involved in what Lillian Faderman described as “Boston marriages” (purportedly chaste relationships), which often embodied the highest intellectual and moral sentiments and allowed for extraordinary independence.

Henry James famously dubbed these women the “White Marmoreal Flock.” They were women who fascinated, astonished, and shocked the expatriate community in Italy with their female marriages and their demand for full equality with their male counterparts. From roughly 1857 to around 1870, they shaped artistic life for this community at a time when the gold standard of artistic achievement among sculptors was a neoclassical model. Thus Rome became an enlightened center of female creativity where female masculinity nurtured lesbian matrimony. Harriet Hosmer, Emma Stebbins, Edmonia Lewis, Anne Whitney, Margaret Foley, Louisa Lander, and Vinnie Ream Hoxie were among the first women, despite the sexism of the period, to achieve international fame in Rome, London, and other cities.

Broken into three parts and made up of seven fascinating and meticulously researched chapters, the book is richly illustrated and deeply archival in its approach. Dabakis’ reflections on the American anti-slavery narrative make this book particularly relevant in light of the national discussion about race that has emerged in the U.S. over the past year.

Despite the visibility of abolitionists in America before the Civil War, white racism prevailed among the expatriate community abroad. One of the major themes that Dabakis tackles is colonization and racial supremacy. This theme is immortalized in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel The Marble Faun, where Donatello, a beautiful Italian boy, embodies an erotic racial stereotype. The celebrated lesbian sculptor, Harriet Hosmer, in her sculpture Sleeping Faun (1865, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) personified Donatello’s idyllic adolescent lassitude as symbolized by the wreath of roses around his head. Hosmer’s work associates these features with the ease, joy, and sensuality of the youthful faun’s sleeping body and the bemused smile that plays around his full lips.

Dabakis’ narrative is driven by feminist theory, cultural geography (the historical and social dimensions of place), and expatriate and postcolonial studies. All of the aforementioned artists addressed emancipation in a transatlantic context. Throughout the 1850s, they maintained close friendships with a host of famous abolitionists. The multiracial (African-American and Indian) sculptor Edmonia Lewis, for example, was a member of the Boston abolitionist community, and she became an active participant in the reform movement. Many viewed their work as anti-slavery sermons in stone. Unfortunately, Lewis was often subject to patronizing flattery or outright criticism because she constructed a public persona that traded upon her ethnic identities throughout her professional career.

In 1869, Cushman was diagnosed with breast cancer and returned to the U.S. with Stebbins, and by 1876 the famous thespian was dead. Hosmer entered into a lifelong partnership with Lady Louisa Ashburton and spent more and more time in England, where she conceived of herself as an inventor and sculptor. Careers that had flourished in Rome throughout the 1870s were eclipsed in the U.S. after the Civil War as a younger generation of women artists, such as Vinnie Ream, came to prominence, adopting professional strategies appropriate to the Gilded Age.

Meanwhile, a new artistic movement was taking hold in Paris to which women traveled in the 1870s and ’80s in search of artistic training and personal freedom, just as they did in Rome a quarter-century earlier. By that time, most women artists were now engaged in painting rather than sculpture and studied in the ateliers of academic painters.

As for emancipation, in 1867 Sojourner Truth bitterly denounced the fact that, while black males were getting their rights, the same was not true for black women: “There is a great stir about colored men getting their rights, but not a word about the colored woman; and if colored men get their rights, and not colored women there is, you see the colored man will be masters over the women, and it will be just as bad as it was before.” With the ratification of the 15th amendment in 1870, politically, all women—but especially black women—were relegated to political invisibility.

Dabakis’ beautifully researched and illustrated academic book establishes the importance of American women artists in 19th-century Rome, where their dazzling accomplishments succeeded in momentarily overcoming the sexism, if not the racism, of their era. The book, despite its strengths, disappoints on a few grounds: Dabakis skirts lesbian desire by applying outdated Freudian psychoanalysis to many of the relationships she describes. For GLBT readers, her evaluations may sound forced and simplistic. Her academic style of writing detracts from the juicy lives these women actually led and the complications of their love lives. Finally, her book spends too much time on Roman politics, which mattered little to these Americans. Indeed, the importance of this book lies in its analysis of the sexual and racial politics of this outstanding group of American women artists.

Cassandra Langer is the author of the recently published Romaine Brooks: A Life (Wisconsin).