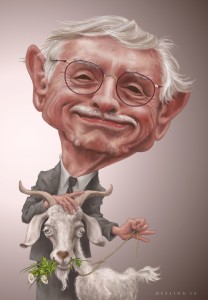

FOR OVER FIVE DECADES, Edward Albee has been an enduring presence in American theater and one its most iconoclastic and divisive playwrights. His first off-Broadway one-act play, The Zoo Story (1959), catapulted Albee into critical recognition as a writer to watch out for. However, controversy would prove to be Albee’s long-time companion.

In 1962, his first Broadway play, the searing psychodrama Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? handily kicked over what remained of “traditional” drama in the U.S. (The title was derived from something he fortuitously found scrawled in soap on a bathroom mirror in a New York bar.) The play’s Rabelaisian humor, raw language, and frank sexual themes inevitably provoked charges that it was anti-marriage and profane. Although the play was initially chosen for the 1963 Pulitzer Prize drama jury, some members of the advisory board protested—half would eventually resign—and the prize for Best Drama was withdrawn altogther that year. But the play did win the New York Drama Critics Circle Award and the Tony Award for best play, and it’s now considered one of the best dramas of the postwar era.

Albee describes his work as “an examination of the American Scene, an attack on the substitution of artificial for real values in our society, a condemnation of complacency, cruelty, emasculation and vacuity, a stand against the fiction that everything in this slipping land of ours is peachy-keen.” His pet peeve is the self-perpetuating canard that the play is cryptically about gay relationships: “The bullshit that Virginia Woolf was about two male couples … every time some damn fool asks you the question because they’ve read it somewhere, you have to sigh and deny it again, they print your sigh and denial, and it perpetuates the falsehood,” he laments. “I don’t know why people don’t pay attention. When somebody’s told them something isn’t true, why don’t they just accept it? … I’m perfectly capable of writing gay characters if I wanted to. There are some gay people flitting around my plays from time to time. I think Butler in Tiny Alice is probably gay. Certainly Jack in Everything in the Garden is gay. … But I certainly wouldn’t put gay couples in a domestic scene on a university campus, which is one of the most conservative establishments imaginable. That would be ludicrous!”

Subsequently, Albee, along with Tennessee Williams and William Inge, would be dogged by allegations of forming a cabal to infiltrate a gay agenda into the American theater. Perhaps this explains Albee’s abiding sensitivity to the “g” word, which has sometimes put him at odds with the PC monitors. However, despite the critical flops (Tiny Alice, Malcolm, The Man With Three Arms, Lolita) and blatant homophobia on the part of some prominent reviewers, Albee had the last laugh, going on to win three Pulitzers—for A Delicate Balance (1967), Seascape (1975), and Three Tall Women (1994)—more than any other playwright besides Eugene O’Neill. In 1996, he received the Kennedy Center’s National Medal of Arts.

Subsequently, Albee, along with Tennessee Williams and William Inge, would be dogged by allegations of forming a cabal to infiltrate a gay agenda into the American theater. Perhaps this explains Albee’s abiding sensitivity to the “g” word, which has sometimes put him at odds with the PC monitors. However, despite the critical flops (Tiny Alice, Malcolm, The Man With Three Arms, Lolita) and blatant homophobia on the part of some prominent reviewers, Albee had the last laugh, going on to win three Pulitzers—for A Delicate Balance (1967), Seascape (1975), and Three Tall Women (1994)—more than any other playwright besides Eugene O’Neill. In 1996, he received the Kennedy Center’s National Medal of Arts.

In 2011, May 26, Albee was chosen a special honoree at the 23rd Annual Lambda Literary Pioneer Awards in New York City, meant to recognize those who have broken ground for LGBT literature and publishing. The award was presented by playwright Terrance McNally, who spoke in defense of his former lover: “He has so avoided gay subject matter throughout his career that people wonder if he’s gay. Well, I’m here to tell you he is. I picked him up at a party in 1960. I thought he was gorgeous and sexy.” McNally expanded on the subject of the “gay art police,” observing that although Albee has “received much criticism from his brethren” over his views about professional queerness, it is an artistic dead end “to limit oneself to one’s own sexual preference. … We don’t have to write as role models, but as individuals, and not just as a minority with an agenda. It’s a lessening of the creative act to limit oneself that way.” Albee later clarified: “Maybe I’m being a little troublesome about this, but so many writers who are gay are expected to behave like gay writers, and I find that is such a limitation and such a prejudicial thing that I fight it wherever I can.”

At 84, Albee is notoriously cagey during interviews, and enjoys a good game of cat-and-mouse, sometimes craftily switching roles with the interviewer. I spoke to the playwright shortly before the revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf on Broadway on October 13th—fifty years to the day of its première—in a production previously staged by Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater. Although Albee underwent open heart surgery in June, walks with a cane, and wears a hearing aid, he is still a good sparring partner, determined not to be categorized and pigeonholed, and can put even an admiring interlocutor through his paces. He is currently putting the finishing touches on a new play, with several more in the hopper.

Perhaps the most poignant development in Albee’s life these days is that, after his grieving period over losing his long-time companion of 35 years, Jonathan Thomas, he has a new love interest, a May-December relationship with a 24 year old artist. As he confessed in an October 8, 2012, profile for New York magazine, “For five years after Jonathan died, I didn’t want to do much of anything. I certainly didn’t think I’d be capable of ever caring much for anybody else or feeling amazing responses to things. But two and a half years ago now, I suddenly, one day, realized that I had fallen hopelessly in love. And really seriously, not just infatuation. Somebody not only beautiful and sexy but enormously talented, genuine, generous. I didn’t think I was going to do that anymore. It was joyous. ‘My God,’ I thought, ‘you’re capable of this still?’And at the same time, I realized a couple of problems. I mean, I am 84 now. … It wasn’t going to be a great, wonderful sexual relationship. But, wow, wasn’t that interesting when I thought it was! Isn’t kidding yourself fun? And so I am getting myself—not out of it … but out of concerning myself with it.”