People often ask how I went from doing gay secrets tours to shady ladies. How did a gay historian get interested in the history of female prostitution? First of all, a gay historian works on the history of sexuality, so the history of heterosexuality is not very far away from his topic, intellectually speaking. But it has much more to do with my tours of the Metropolitan Museum.

To find the works of LGBT interest in the Met, you have to know what you’re looking for: it’s like following a secret trail through hostile territory. But while you’re following it, you see a lot of works focusing on various kinds of prostitutes or scandalous women, including of course some very noticeable nudes.

Courbet’s Courtesan

For instance, on the way to the 19th century French Lesbian artist Rosa Bonheur’s self-portrait, my groups pass the unbelievably lascivious nude above. Sometimes I get the feeling that people don’t understand why I call her lascivious, but if you think about it, what is she meant to be doing? To put it simply, she’s lying on her back, playing with a “bird”—a symbol of male sexuality. And as Dr. Ruth pointed out when she took my tour, she’s also clearly sexually aroused: she’s flushed, and her nipples are erect.

Interestingly, in 19th century France, this was not regarded as a scandalous painting. An oversexed woman in a luxurious setting was clearly a courtesan, and courtesans (called demimondaines, cocottes, etc.) were an accepted part of French life at the time. There was nothing scandalous about a sexually aroused courtesan, so long as you didn’t portray her too realistically. This painting idealizes the female form, or as we would say ‘airbrushes’ it—and according to the 19th century French, that is what artists were supposed to do.

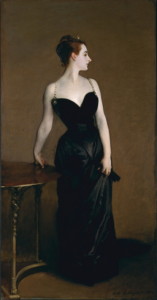

Sargent’s Scandal

This is in contrast to another painting in the museum that came to my mind as soon as I thought of the shady ladies tour, Sargent’s ‘Mme. X.’ This painting was a great scandal at the Salon 18 years after Courbet’s Woman with a Parrot, although to a modern eye it’s much less racy. I think, though, that the difference between the sitters’ statuses was important.

The woman with a parrot was a courtesan, while Mme. X was a society lady, so standards were different. A courtesan could lounge on her back in the nude, but a society lady couldn’t even wear a low-cut gown suggesting the shape of her breasts. And in the original version (which we know from an old photo that was discovered 30 years ago), one of her shoulder straps had also fallen down.

Now *that* was scandalous, implying that she was either about to get undressed or had just pulled on her clothes—perhaps after an adulterous fling. In fact, Sargent—and his model—were so upset by the scandal that he asked to be able to repaint the painting during the Salon and, when he was refused, repainted the shoulder strap as soon as he got the painting home to his studio.

Mistress to a King (or Two)

Of course, the tour doesn’t consist only of things I already knew when I first thought of it. After I came up with the idea, I took a long wander through the museum, hunting for more courtesans and royal mistresses, and I came up with a lot of great material, including for instance a make-up table that belonged to one of Louis XV’s most famous mistresses, Mme. de Pompadour. Probably my favorite of all, though, is this portrait of Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott. The Met is very conservative about labeling paintings, and it almost never mentions anything sexual, but in this case, even the Met calls her “a woman of great beauty but easy virtue.” And that she was.

Grace Elliott was the mistress of a number of important men, including the the future George IV, and Louis XVI’s cousin, the Duc d’Orléans—the one who voted to execute his cousin but later ended up on the guillotine himself as well. What I consider most interesting is that the portrait was commissioned by her main lover, the Marquess of Cholmondeley (pronounced ‘Chumley’) and hung in his house—although he was married. This shows (I think) that for an 18th century aristocrat, having a famously beautiful mistress was a point of honor: maybe it was even *better* if you had shared her with the Prince of Wales….

In any case, as you can see, Grace Elliott was quite an addition to the Shady Ladies tour, which covers sex workers and scandalous women, from ancient Greece to the 19th century, with much fascinating social history and history of sexuality….. Join Oscar Wilde Tours, and learn that the Metropolitan (or rather art itself) is more fun than you realized!

Discussion1 Comment

Coincidentally, I recently read a review of the John Singer Sargent show at the Met (June 30-October 4, 2015) by Jean Strouse in the The New York Review of Books.